Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Cylinders

Unique Content

If what you are assessing is a commercially produced item, more than likely it is not "unique." It may be unique to your archive but, at some point, it was mass produced. Truly unique items often require priority in preservation because they may be the sole remaining document of this material.

First Generation / Master / Original Items

When we talk about "generations" in audiovisual preservation, we're talking about "copies." If something is a second-generation item, it means that it has been copied from the original, or "master." (We should note that sometimes people use the term "master copy," which can be confusing. A master copy is a master.)

The original audiovisual item is the most valuable iteration of the item that you can have because it should have the best audio and video quality possible when compared to its copies. (This assumes, of course, that the original has been well preserved and is in good shape.) Another reason for giving priority to the original is that it may be the only iteration there is of the item. This means that any damage that occurs to the original could mean that information is lost forever. Even if you have a copy, damage to the master means that you must resort to using copies that may have inferior picture and/or sound.

Following best practice, you should use the master as little as possible and store it in the best conditions possible. Many institutions use their master once to make a "secondary master." This secondary master is then used to make copies for access. Ideally, you should almost never have to return to the master; it can stay in the best possible storage conditions in perpetuity. If the item you are assessing is a master, then it will be higher in priority for reformatting and preservation than those items that are copies.

Risks of Handling/Playback

Playback and handling are the leading causes of damage to audiovisual items. A film, for example, is most likely to be damaged being fed into or coming off of a projector. Any playback machine, no matter how well maintained, can cause damage to an audiovisual item. That said, it is still best to maintain your playback equipment alongside your audiovisual items. Regular service and cleaning is critical to helping minimize the risks of playback for your materials. An item may sometimes only have one play left before it is permanently damaged, rendering it unusable. If an item must be played back, an operator skilled in handling the playback equipment and at identifying problems with the media prior to playback should be the only person allowed to play the material in question. Allowing media to be handled and played back by untrained staff or patrons is a danger to the material.

Playback Equipment

One of the great challenges of audiovisual preservation is the fact that AV materials require playback machines in order to "decode" the information stored on the materials. This applies to all audiovisual formats. Of course, a further complication is that the playback machine must be appropriate to the format of the AV material. When we consider how many hundreds of AV formats there are, we see that this is a large challenge indeed. The playback machine must also be well-maintained because it can damage the materials fed into it if the machine is in poor repair.

It is important to look at your collection and consider what formats are most valuable to your institution, what formats are accessed the most by your users, and what format you have the most of. These will be the materials for which you should have playback equipment, if at all possible. This can be challenging, but there are avenues you can explore. Local television and radio stations, colleges and universities (particularly those with film, art, communications, or journalism departments), and audio recording studios often have older equipment that they no longer need. As a result, you may be able to procure equipment at very reasonable prices. However, keep in mind that universities and colleges often have considerable red tape when selling or donating their equipment, so you should be prepared to invest some time and effort when working with them.

Never put any collections materials into a playback machine without first testing that machine. Have a "dummy" item that you can test a piece of equipment with. For example, you can designate a VHS tape as your dummy tape and use it to test your recently procured and/or serviced VCR. Ideally, this tape should neither be an item that is a part of your collection nor have any value so that it will make no difference if you damage the item.

We do not recommend that you service a piece of playback equipment yourself because of the potential for damage to both the equipment and AV materials. We recommend that you find and establish a relationship with a local repair service. Maintaining your playback equipment should be at least as important as maintaining your collections.

If you do not have (and cannot acquire) playback equipment, it does not mean that the AV materials are without value. In fact, it may be an indicator of higher preservation priority if the playback equipment is obsolete or unavailable to you at your archives. These materials are often especially vulnerable. Film duplication vendors will most likely have the equipment and can transfer the film to a format accessible to your archives.

Remember, if you have materials with no way to play them back, these items will have diminished accessibility and can end up costing you time, effort, and money when you have to send them out to be transferred to a format your institution does have playback equipment for. If you plan to digitize your materials, you will have to have well-functioning playback equipment for each format you decide to digitize.

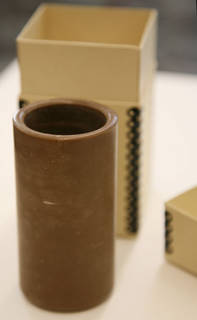

Cylinders - Orientation in Storage

Cylinders should be stored standing on their ends like a drinking glass.

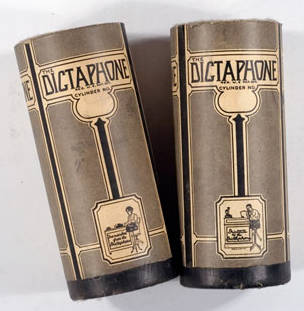

Cylinder - Appropriate Container

Containers protect the surface of the recording from dirt, dust, mold, and vermin. These contaminants can damage the surface of the recording, which can affect its sound quality and even render the recording unplayable. Archival quality boxes are available specifically for cylinders. These are small acid-free boxes that often have a cylindrical baffle inside. The cylinder is placed on the baffle to secure it within the box and to prevent it from excessive movement while in storage. Cylinders should be stored in containers designed to support them vertically, bearing the weight at the bottom and protecting the surface from any pressure or contact with the container.

The container can speak volumes on the storage history of the recording. Is it moldy? Does it appear to have water damage? Is it falling apart? A container should protect the recording without damaging or leaving contaminants on the surface. Original paper containers may also deteriorate and leave fibers, which can abrade the delicate recording surface. Since grooved media is especially susceptible to damage from dirt and contaminants, it is important that these recordings are housed in appropriate containers.

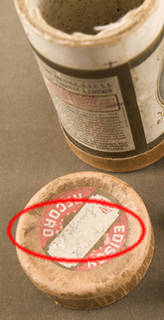

Cylinder - Labeling

If your item has any kind of labeling on the container, the item itself, or any related material, we highly recommend that you revise the description of this item and enter this information in the notes field.

Correct labeling on a container can offer important clues about what is on the cylinder. If you are replacing a container that has labeling information, it is important to transfer this information to the new container or label. Container labels should be used with caution, however, as containers are frequently reused or switched by accident. If there is content information on the container, verify it. Content information is often found on the edge of the cylinder, if available.

Cylinder - Physical Damage

Because of their age and fragility, ALL cylinders will be considered a higher preservation priority.

Cylinders, especially the oldest wax cylinders, are susceptible to damage because of the age of the media and the delicate nature of the grooved surface. Surface damage from contaminants, abrasion, and general decay can result in cracks, pitting, scratches, and groove degradation, which can affect the quality of the sound and content. Additionally, careless playback using improper styli and equipment can cause groove destruction. If the cylinder is on a cardboard core, check the core for swelling or damage.

Mold / Pest Damage

Mold

MOLD CAN BE TOXIC. Proceed with caution when examining items for mold. Do not handle moldy materials longer than necessary. If you find a moldy item, immediately seal it and its container in a sealable plastic bag until conservation action can be taken.

Cylinders are susceptible to mold, especially the earliest wax cylinders. Mold can affect the sound quality of a recording and can damage the delicate recording surface. High humidity and temperature in your storage area can foster the growth of mold on your cylinders and associated containers. Mold typically has a dull, lattice-like appearance. You can identify mold if you see whitish, splotchy surface contamination. If you see white or brown patches or strands on the cylinder, chances are that you are dealing with mold.

Pests

Pests like insects and rodents tend to like paper and textile materials more than audiovisual materials. That said, pests can still do damage to your AV collections. Insects can be attracted to the organic components of film emulsion, although film cans, both plastic and metal, tend to keep most pests out. When assessing the exposure of your collections to pests, it is necessary to look not just at the materials themselves and their containers but also to look around at the rest of the environment. Insects and rodents tend to leave droppings in areas they inhabit. Insects leave behind a substance called frass, which is the undigested fibers from paper. If you see droppings and/or frass in your storage area, it is a strong sign that your materials are being exposed to pests. Small, irregular holes on paper-based containers (e.g. sleeves for grooved-disc audio recordings) are also a sign that pests have attacked your materials.

Some tips for reducing your materials' exposure to pests are to refrain from eating anywhere near your collections materials. Crumbs draw rodents and insects, so keep food far from your collections. Another tip is to be careful opening donated materials when you receive them. Pests can hitch rides into your facility on these materials, so having a good, clean staging area where you can inspect donated items for, among other things, pest-related evidence can help you reduce your storage environments' exposure to pests.

Cylinder - Dust and Dirt

Dirt and dust on the surface of a cylinder can be especially damaging. A dirty cylinder played back without prior cleaning can cause the stylus to collect the debris and drag it through the grooves. This can cause irreparable damage to the recording and adversely affect playback sound quality. Thus, all recordings should be cleaned before playing them back.

Playback Quality

It is often difficult to truly assess an item's condition without playing it back. It is entirely possible to have an item that, to the eye, appears to be in good condition, but when played has very bad sound quality. Playback, however, carries with it the risk that your item could be irrevocably damaged and/or could cause damage to the playback machine. For this reason, we do not recommend playback as a means of assessment. However, if you do play an item and find that the sound quality is poor, it likely means that the item is in need of reformatting.

Documentation

Having additional documentation about your item can help inform your future preservation decisions. If you have any past documentation about playback or cylinder quality, this information can be extremely useful in assessing the cylinder without having to subject it to playback risks. Additionally, documentation may provide evidence of past preservation measures taken on the content or item. You should always document any preservation measures that you take on your materials. This provides evidence to future preservationists and researchers about the path that the content/object has traveled.

Playback carries with it the risk that your item could be irrevocably damaged by the playback and/or that the playback will cause damage to the playback machine. As a result, we don't recommend playback as a means of assessment. However, a strictly visual inspection of a item will not provide all the clues about the item's sound quality. For this reason, it is a good idea to check around your institution for any documentation on the item. It is possible, for example, that there may be notes indicating the playback quality from the last time the item was accessed.

Your documentation should NOT be stored with the item. You should store your documentation (e.g. notes written on paper) in a separate physical location. A physical object itself, paper has numerous conservation issues and can be more damaging than helpful when combined with other collection materials. For example, paper can damage your item by shedding fibers that abrade the item's surface. If you track your items via electronic means, you may be able to note preservation history in your electronic tracking system and in appropriate metadata fields.