Preservation Self-Assessment Program

User Manual

- PSAP's History and Background

- PSAP's Technical Specifications

- Who Should Use PSAP?

- How Should PSAP Be Used?

- Preparation and Set-up: What You Need Before You Get Started

- PSAP Walkthroughs

- Cloning Existing Records

- Moving Existing Records

- Interpreting PSAP's Assessment Scores and Reports

- Importing and Exporting Data

- Why Descriptive Data is Important

- Using the Supplemental Guides and Other Helpful Resources

- Using Basic and Advanced Help

Supplemental Guides

Understanding Use of Certain Fields and Approaches in the PSAP

- Preservation Assessments and Surveys

- Assessing a Repository or Collection Using a Sample

- Understanding Significance

- Understanding Dates

Understanding Institutional Practices

- Preservation Planning

- Environmental Guidelines

- Use and Access

- Understanding Metadata

- Exhibition Guidelines

- Collection Development Policy

- Disaster Preparedness

Additional Information and Tools

- When to Bring in a Professional

- Disaster Resources and Recovery Vendors

- Grant Resources

- The Role of the Artifact in the Age of Digitization

- Mapping to Past Perfect

PSAP's History and Background

PSAP has been made possible with federal funding through an Institute of Museum and Library Services National Leadership grant, administered by the Preservation Program at the University of Illinois Libraries. The project’s scope was to further enhance and migrate a previously developed project (the Audiovisual Self-Assessment Program, AvSAP to create a web-based open source software application that led users through preservation assessment of audiovisual, photographic, paper, and bound materials commonly held in libraries, archives and museums. The project was funded for development from December 2012 – December 2015, with public release of the application in the late spring of 2015. As the result of a no-cost grant extension, in late 2016 the scope of the PSAP was expanded to include basic museum object materials made of stone, ceramics, glass, and metal.

If you need help cross-walking data from the AvSAP to PSAP, please contact Project Lead, Jennifer Hain Teper.

PSAP's Institutional Partners

- Chicago History Museum

- Heritage Preservation

- Illinois Heritage Association

- Illinois State Archaeological Survey

- Illinois State Library

- The Institute of Museum and Library Services

- The McLean County Museum of History

- The Spurlock Museum

- The University of Illinois Conservation and Preservation Unit

- Urbana Free Library and Champaign County Archives

PSAP's Technical Specifications

The web-based PSAP application is optimized for the recent versions of the following web browsers: Firefox, Safari, Chrome, Opera, and Internet Explorer. PSAP is platform-independent and is designed to run on the entire spectrum of internet-capable devices, from desktop and laptop computers to handheld and tablet devices.

The PSAP project has been developed using open source software and the code is available for those interested in hosting a local copy of the PSAP or modifying a local copy. All technical information is hosted on GitHub. The GitHub wiki also offers background and documentation on the development and functionality of the software. The University of Illinois is committed to providing free hosting and long-term storage (backed up nightly) and maintenance for the PSAP application as well as for all data entered into and generated by the program.

Who Should Use PSAP?

PSAP is intended as a tool to help individuals and the staff of smaller institutions assess collection materials. It is not intended to be a replacement for professional conservation/preservation consultants' assessment of individual items or collections, but can be used as a first step towards a more fulsome professional consultation, to define project scopes, or to justify funding for preservation efforts.

How Should PSAP Be Used?

The PSAP is first and foremost an assessment tool, but also contains significant educational components developed to assist non-specialists in better understanding preservation of the materials in their care. The program can be used on unprocessed collections as well as fully described materials. While the most meaningful results will be produced by using the PSAP to evaluate collection at an item-level, the PSAP can also be used to evaluate collections using sampling techniques (this approach is discussed in detail later in this user manual, see Assessing a Repository or Collection Using a Sample) so that only a portion of a larger collection need be inspected. The information generated from the PSAP, in the form of 1) individual preservation scores for items, 2) aggregate preservation overviews for collections, and 3) summary scores for institutional preservation practices and storage environments, will offer users quick, numeric and graphic representations of the highest preservation needs in their collections, which can lead to more detailed assessment or review, consultations with professional conservation or preservation professionals, rehousing projects, or other preservation projects to improve long-term accessibility of materials.

Materials and Formats Covered

The PSAP covers architectural, audiovisual, cartographic, paper-based, photographic, and photomechanical materials, as well as the following inorganic object materials: ceramic, glass, stone, and metal.

Audiovisual formats/materials include:

- Audiotapes: 1/4" Open Reel, 1/2" Open Reel, 1" Open Reel, 2" Open Reel, 8-Track, Compact Cassette, Continuous Loop Cartridge (Cart), Digital Audio Tape (DAT), Digital Compact Cassette (DCC), Microcassette

- Films: 8mm, 9.5mm, 16mm, 35mm, Super 8mm

- Grooved Cylinders: Plastic, Wax

- Optical Media: Compact Disc (CD), DVD, LaserDisc (LD), MiniDisc (MD)

- Phonograph Records: Aluminum, Lacquer, Shellac, Vinyl

- Videotapes: 1/2" Open Reel, 1" Open Reel, 2" Open Reel, Betacam/Betacam SP, Betacam SX, Betamax, D-1, D-2, D-3, Digital Betacam, DVCam, DVCPro, HDCam/HDCam SR, HDV, MiniDV, U-matic/U-matic SP, VHS, Video8/Hi8

- Wire Recordings: Wire Audio

Bound book formats/materials include:

- Binding Types: Accordion, Double Fan Adhesive (DFAB), Perfect, Punch-and-Bind, Spiral, Stab, Stapled, Through-the-Fold, Oversewn

- Board Types: Paper, Wood

- Coverings: Cloth, Leather, Paper, Parchment, Tawed

- Ink Types: Ball-Point Pen, Carbon Black, Colored Pencil, Copying Pencil, Dye-Based, Felt-Tip Pen/Marker, Graphite, Iron Gall, Pigment-Based, Typewriter Ribbon, Wax-Based Pencil/Crayon

- Paper Types: Acid-free, Coated, Newsprint, Rag Paper, Proprietary, Tracing/Transparent

Photographic and image formats/materials include:

- Cased/Direct Photographs: Ambrotype, Daguerreotype, Tintype

- Color Prints: Chromogenic Color, Color Carbro, Dye Transfer, Silver Dye-Bleach

- Digital Prints: Inkjet, Laser

- Instant Photos: Black-and-White, Color

- Microforms: Mixed Aperture Card, Paper Microcard, Paper Microprint, Plastic Microfiche, Plastic Microfilm

- Monochrome Prints: Albumun, Carbon, Cyanotype, Gelatin POP, Glossy Collodion, Matte Collodion, Platinum/Palladium, Salt, Silver Gelatin DOP

- Negatives: Albumen Glass, Chromogenic Color, Collodion Glass, Gelatin Glass, Silver Gelatin

- Photomechanical Prints: Collotype, Gravure, Letterpress Halftone, Offset Lithography, Woodburytype

- Slides/Transparencies: Glass Autochrome Slide, Glass Black-and-White Slide, Plastic Black-and-White Film, Plastic Color Film

Unbound paper formats/materials include:

- Architectural Drawings: Aniline, Blueprint, Diazo, Electrostatic, Ferro-Gallic, Gel-Lithograph, Hectograph, Photostat, Van Dyke, Wash-Off

- Office Prints: Carbon Copy, Carbonless Copy (NCR), Color Photocopy, Copybook/Roller Copy, Diazo Print, Diffusion Transfer, Dual Spectrum, Electrofax, Electrostatic Copy (Xerox), Impact Print, Inkjet Print, Laser Print, Lithograph/Office Litho, Photostat, Spirit Duplicate, Stencil Copy, Thermal Print (Thermofax), Typography

Object materials include:

- Archaeological materials: previously buried (ground or water) whole and fragmented glass, stone, metal, and ceramic

- Non-archaeological materials: glass, stone, metal, and ceramic items that have never been buried

Materials and Formats Not Covered

The PSAP does not address the conservation or preservation needs of audiovisual formats originating outside of the United States.

It is not intended to be used for the assessment of materials other than physical audiovisual recording media, books, papers and image materials, and inorganic museum objects made solely of ceramic, glass, stone, or metal. The PSAP should not be used to assess agricultural tools, architectural materials, artistic installations, artwork, botanical materials, clocks, non-metallic monetary units, commercial/home electronics, computer hardware and software, digital preservation strategies, engravings and etchings, equestrian and livery equipment, firearms, funereal objects, furniture, household objects, human and/or other animal remains, industrial and other non-commercial equipment, maritime collections, military paraphernalia, organic materials, paintings, plaster casts or reproductions, raw and processed datasets, scrapbooks, outdoor sculptures, stamps and seals, and textiles. Of the above objects, only non-composite objects of ceramic, glass, stone, or metal are included in the PSAP.

Still, there are areas of overlap between format and material types that enable the PSAP to be of some limited use for certain resources. For example, while the PSAP does not explicitly address the preservation of scrapbooks, one certainly could use advice given in the PSAP's supplemental guides as a resource for the preservation of common scrapbook components like paper media, inks, and photographs. Similarly, composite objects are not directly addressed by the PSAP as preservation assessment and needs become complicated when multiple materials exist on one object. For example, a glass-and-metal object cannot be treated as though it were solely glass or solely metal, as the two materials can react differently in different environments-- creating additional concerns for care, handling, and storage that will not be addressed by PSAP.

Preparation and Set-up: What You Need Before You Get Started

In order to get started with PSAP, it is necessary to register either yourself or your institution. Multiple users can register to be affiliated with the same institution, however being linked to an institution requires authorization by PSAP administrators. Authorization is intended solely to prevent malicious access to institutions' and individuals' private information. Registration is available off the main project website: . To view the PSAP application without registering, you may enter the application using the logon ID: Testuser, and the password: “Rjc9n!”.

Planning for Your Time on the PSAP

Expect that your first time into the PSAP will go a bit slow. As a first time user, you will be asked to enter information about your institution and storage/exhibit locations that you will only need to enter once. Additionally, if you are not familiar with the types of materials you are assessing, you will be asked to identify formats of the items in your collection. The PSAP is designed to give you as much in-depth help as you need to lead you accurately responding to our questions, however, once you get more familiar with the format types in your collection (i.e. you know what a silver gelatin developing out photographic print looks like) your Collections ID skills will improve. While we cannot estimate how much time each evaluation could take a user, we have made every effort to minimize our questions to the very most critical in order to evaluate preservation effectively. Our goal has been that each item takes only a few minutes from start to finish once you are comfortable with the interface and your most common formats.

For further information on assessment preparations, see the supplemental guides on Material Inspection and Cleaning, Playback, Record Protection Mechanisms, and Use and Access.

PSAP Walkthroughs

General Lay-Out

PSAP allows interactions with assessment reports and scores through either an administrative or staff user dashboard. Dashboard options are designed differently in order to better meet the needs and purposes of staff versus those of administrators.

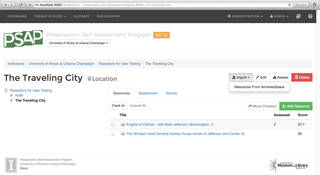

The website is organized with some sense of hierarchy between four views of--and levels of access to--assessment details. The Institution view is at the top level, followed by Repository, Location, and Resource. This hierarchy displays on the left side of the application at all times to aid with navigation throughout the assessment process.

Getting Started

PSAP provides a separate document, called Getting Started as a quick start reference for users. This document offers a simple, graphic inteface and short video clips that illustrate the basic navigation through the PSAP.

Registering an Institution

The first step towards using PSAP is to register yourself as either an independent user or as part of an institution. To begin registration, you must first sign up for an account. Click on the blue 'Sign up now' script in order to be sent to the registration form. Once on the sign up form, you should provide your name and email address. You will also have the ability to request a specific username.After you have completed the web form, a password will be emailed to you (logon requests are vetted by a real human, so this request process may take up to 24 hours). Once you have received your logon, direct your browser to / and enter your assigned user name and password. Then, click the blue "Sign in" button.

As a first time user, you will view a welcome panel upon your first logon which will give you some pointers for your first use of the PSAP, as well as ask you to participate in a survey that will collect a small amount of information about your knowledge of preservation practices and your institution (if you have one). This survey information is valuable to us in assessing the success of the grant project and could help us in future iteration of the PSAP, we encourage you to take the five minutes to fill out the survey.

Your Dashboard

Once you have logged on, you will be directed to your dashboard. Depending on the type of user you are your dashboard may appear differently. A very small number of users who are coded as "administrators" will have a different format dashboard with access to other users accounts who they manage, however, the vast majority of users will have a "normal user" dashboard. In general, however, any dashboard will have several key components:

- You will have a collapsible resource tree on your left showing institution, repositories, locations, and resources that have been entered into the PSAP for quick navigation;

- You will have a quick link to the last resource added to the PSAP.

Click here to view an overview of the PSAP including navigating your dashboard

Introduction to the Institution Screen

Once your account has been set up, there are several different functions and views that you can access through the Institution screen, including viewing the differenent repositories affiliated with an institution, searching all resources within an institution, viewing assessment reports, and main contact information for an institution. Some of this information may only be utilized once assessments of individual resources has been performed.

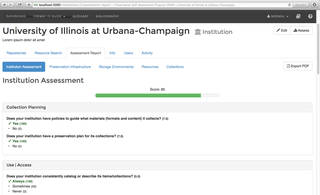

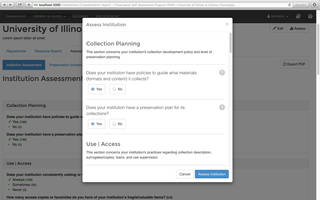

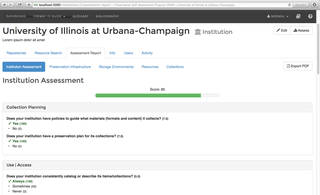

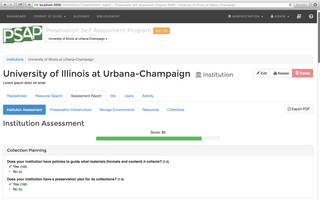

Assessing an Institution

Once you have registered an institution and feel comfortable navigating your dashboard, it's time to start the process of assessing your institution, locations, and resources. As the first step towards assessing your collection, PSAP will ask you to first assess your institution and then to assess your location and the resource itself. Although your responses to the institutional questions are important, and will be scored, they will not affect your final resource scores. You will only be asked to assess your institutional preservation practices once, and will not need to repeat this step once it's completed. Your resulting score can be used to evaluate the "preservation savviness" or existing preservation infrastructure of your institution.

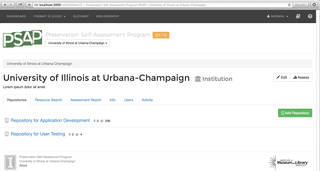

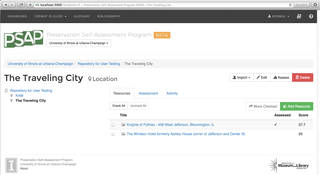

Adding a Repository

Once the institution has been registered and assessed, you will need to add information about the repository storing your resources. One institution, such as the University of Illinois may have many repositories, such as the "University Library", "University Archives", or "Spurlock Museum", for example. Most users will work in only one repository and in smaller organizations, the institution and repository may be the same.

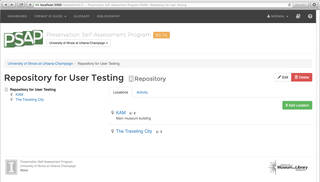

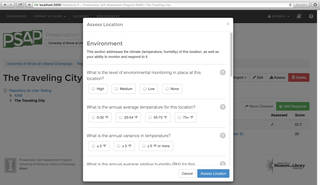

Adding and Assessing a Location

Now that you have added and assessed the institution and added the repository, you will need to enter information about the location of your resources within its repository. In order to do this, you will need to first add the location and then to assess it, by clicking on the "add location" button in the top right of the screen.

Information on your locations (and the scores generated from their assessments) is saved and each can be selected as a saved location as you add resources to the PSAP.

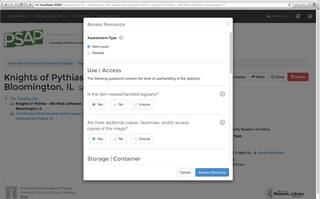

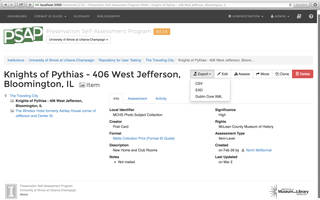

Adding and Assessing a Resource

Now that you are done entering information about your institution and your resource's repository and location, you can finally begin the process of assessing your resource. Similar to how you added your institution and location before assessing them, you must first add a resource before assessing it.

To create a resource, click "add resource to assess", give the resource a name (this can be based on unique identifiers already in place in your collection) and select whether your resource is a collection with items within it which you want to be able to assess as a collection, or whether it is an item unrelated to a collection. You will will also be asked to identify the format of the resource, if at an item level (see the Collection ID Guide for assistance with format identification) and will be given the option to provide descriptive information about the collection/item. This descriptive information is optional. See Why Descriptive Data is Important for more detail on the value of these questions.

Click here to view a short video on creating collections.

Once you have created a resource, select the resource and click on the "assess" button. Then, in the pop-up window, you will answer guided questions about:

- Storage containers and orientation

- Storage environments in which the item resides

- Physical condition and defects like inherent vices, mold exposure, and structural problems (e.g. the amount of scratches and dust on a grooved audio record)

For each question, you simply choose the answer that best describes the storage or physical condition of the item. Although "Unsure" is an option in many cases, the assessment becomes more diagnostic and useful the more completely you answer each question.

In most areas, the terms used do not require foreknowledge of cataloguing or metadata practices, although the information provided will be more accurate with such training. Since PSAP is designed to aid users with any level of experience, basic help windows are built into each question, so you can always look up unfamiliar terms. There is also a more detailed advanced help guide, glossary, format identification guide, and a number of supplemental guides to provide you with further guidance.

Cloning Existing Records

To help speed along the assessment process, the PSAP is equipped with a cloning functionality. This tool is most helpful when you are assessing a run of individual materials that share most or all of their descriptive information. For instance, a collection of 25 8x10 black and white photographs of the same subject will share many data points. The clone function will allow you to create a new record that exactly copies the information from an existing resource record, reducing the need to re-enter that information manually. When you select to clone a resource (by clicking on the “Clone” button on the upper right of the resource page), you will be prompted to clone the record either “including the assessment”, or “without the assessment”. If the condition or storage of the object is in any way different than the previous resource, you should choose to clone without the assessment. However, if all the materials are stored together and in the same condition, you may also choose to clone the assessment along with the resource information. In either case, be sure to change the name for the resource so that each item is differentiated.

Moving Existing Records

Another handy tool offered by the PSAP is the “Move” function. This function can be used to update records if an item or collection is shifted from one location to the next. Resources can be shifted individually from the resource page by clicking on the “move” button, but can also be shifted in batches from the location screen by selecting resources found listed under any one location (items are selected by clicking on the checkbox to the left of the resource) and then clicking on the “move checked items” button at the top right. In either case, you will be asked to select a new location for the selected resources and the PSAP will change their location and scores to reflect this modification. This functionality can be particularly useful if you are considering the best long-term storage for an object or collection of objects. Once the descriptive, format, and condition information are entered, materials can be “moved” to different locations and scores can be compared to find the best location for long-term preservation.

Deleting Records

While the University of Illinois is committed to providing free long-term storage (backed up nightly) and maintenance for the PSAP application in order to protect against any data-loss caused by system failure, PSAP data that is deleted by a user is not recoverable. If a user chooses to delete a resource, location, repository, or institution, then all information associated with those entities will be permanently deleted. This means that if a user deletes a location, then any objects associated or “housed within” that location are also deleted. Similarly, if a user deletes a repository or institution, any locations and resources within the repository or institution will also be deleted. PSAP administrators are unable to recover any PSAP data that are purposefully deleted by a user, so please be thoughtful when deleting data in the PSAP.

Interpreting PSAP's Assessment Scores and Reports

Once you have completed entering in assessments for your institution, locations, and at least one resource, you will have a complete PSAP score for that resource. Scores can be viewed individually by clicking on the “Score Summary” tab on the Assessment Report screen. You can also click on "Assessment Report," under the "Dashboard" on the left side of the screen or on the "My Dashboard" page to view aggregate scores for all the information you have entered for your institution. Many factors go into generating an item's ranking: the physical condition of the item, the format of the item, the conditions of the environment in which the item has been stored, and the container (or lack thereof) of the item. Many questions in the storage environment and item-level assessment sections have weights that affect the final score (and thus the ranking) of an item. The more questions you answer about an item, the more diagnostic the item's score will be. With more diagnostic information about each item, your assessment report will be more accurate and complete at the end of the assessment. You can use this list to plan your preservation efforts and make more targeted budgetary choices. The PSAP assessment report can also be used to document your specific needs to granting agencies and your organization's budget managers.

For more information about interpreting data from assessments, see Preservation Assessments and Surveys.

How Should I Interpret Assessment Scores?

Scores are generated by pulling information from values entered for the location, format, and condition of a given resource and combining them to give a final value between 0 and 100, where 0 is the lowest possible score and 100 is the highest possible score. Note that scores of 0 and 100 are both nearly impossible actually attain for your final score (though possible in sections such as Location), and most final scores actually lie between 50 and 90. The final resource score is weighed such that the condition of an item is weighted as half (50%) of the score, the format of the resource is 40%, the location of the resource is 5%, and the temperature and relative humidity of the location are each 2.5% for a total of 100% of the total score. This weighting of scores was developed by the project team to represent the understood balance of the current condition of the object with the inherent vice of an individual artifact (format) and the effects of the environment on that particular format (Location, Temperature and RH).

Click here to view a short video on interpreting your PSAP scores.

A summary judgement of the preservation/conservation needs of an item or collection depends on the value of the final assessment score. Broadly speaking, a score can be understood as: low = below 60, moderate = 60-80, and high = 80-100.

How Should I Interpret Assessment Reports?

PSAP's assessment reports display several fields: collection name, item name, location (i.e. the storage environments you have assessed), the total assessment score, item format, item significance, and the notes field for each item. The list can be sorted by each of these fields. Although the PSAP score is out of 100, the obsolescence of the various media types and their inherent instability makes it very difficult to get a score near 100. It is very likely that your highest scores will be far lower than 100. Don't fear! Many materials are, generally speaking, not built to last. It's very common for PSAP assessments to have few items that score higher than 80.

Click here to view a short video on understanding PSAP reports.

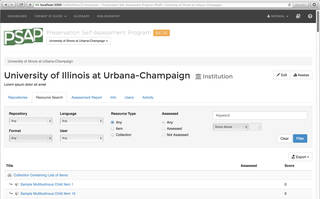

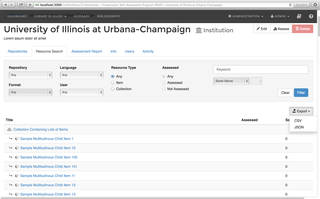

Importing and Exporting Data

PSAP data is designed to be exportable as spreadsheets in common formats that can be easily integrated and manipulated with an institution's data management services. The data can be exported both as a PDF and a CSV or JSON file.

In order to export a pdf, you must be at the institutional level. Once you select Assessment Report, the export option will appear on the right.

In order to export a CSV/JSON files, you must be at the institutional level. Once you select Resource Search, the export option will appear on the right. Click on it to select the format that you prefer.

Exporting Metadata

In order to export metadata, you must be at the item level of an assessed resource. You will be provided with the option of exporting metadata as CSV, DC, and EAD files. Dublin Core (DC) metadata is exported as DC-XML code and is only available at the item-assessment level. Encoded Archival Description (EAD) metadata is exported as EAD-XML code and is only available when one is assessing at the collection-sample level.

Importing Data Files

As an added feature, we have designed the PSAP to import EADXML data from the ArchivesSpace. software. To export existing records from ArchivesSpace, see http://www.archivesspace.org/importexport.

In order to import a file, you must be at the location level. You will see the option to import data through a white dropdown box. Click on that and select 'Resources from ArchivesSpace.' Then, choose which files you'd like to upload from your downloaded and saved data.

Why Descriptive Data is Important

We purposefully require minimal descriptive information about the materials to be assessed both to streamline data entry, but also because that information may not be available for all materials, however, that should not downplay its importance.

If your institution already has a catalog or inventory of your collections with information about the materials held within them, you may choose not to record descriptive information in the PSAP, but instead note a barcode, call number, accession number, or other unique identifier in the PSAP that will help users link between the preservation assessment in the PSAP and the descriptive information about the object. This will help better prioritize materials for preservation later, when the value of materials to the collection is necessary to create priorities.

If your institution does NOT have a catalog or inventory of the collections you wish to assess, entering descriptive information will be helpful for several reasons.

- It will help you describe your collections to others

- It can be used to create inventories or finding aids to help users and staff

- It can be exported into Past Perfect software. See Mapping to Past Perfect for more information on moving data from PSAP to Past Perfect

- It results in better intellectual control over your collections allows you to better assess priorities for preservation, or other actions

While PSAP focuses mainly on the physical condition of the items being assessed, no assessment can be complete without acknowledging the significance of an item to the repository. Significance refers to the intellectual content of the item and its value to your collection. During the item-level assessment, PSAP asks you to rate the significance of each item. This rating does not affect the final assessment score but serves to "flag" items that have high significance. The collections manager can then consider the significance of items when using the PSAP preservation assessment report. For example, a collections manager may decide to focus preservation efforts on an item high in significance even though it scores low on the PSAP assessment report. The help window for this question provides several methods of assessing significance to help you generate a useful answer. See Understanding Significance for more information.

Using the Supplemental Guides and Other Resources

IN addition to this User Manual, there are many resources that may be useful to PSAP users. There is a Glossary of Terms to help those new to preservation better understand the terminology, as well as a Selected Bibiography of resources used to develop that PSAP that may be used by those seeking more information on specific topics. The User Manual and the Collection ID Guide (CIDG) also offer supplemental guides that speak to different aspects of conservation and preservation needs, as well as quick reference "cheat sheets". These guides provide additional information geared towards helping users either use the PSAP more effectively, or better understand the preservation needs of their collections in a broader scale. The Supplemental guides are broken into four areas of focus:

- Audiovisual-Specific Additional Information (in the CIDG)

- Identification Cheat Sheets (in the CIDG)

- Material/Format Additional Information (in the CIDG)

- Policy/Procedure Information (later in this User Manual)

Using Basic and Advanced Help

PSAP is designed to be both an assessment tool and an educational tool. So, for example, the illustrations and descriptions in the Audiovisual Media section of the Collection ID Guide provide guidance on identifying audiovisual formats. If you aren't clear what the question is asking, you can click on the question's "help" icon located next to the symbol. This will open a window to the right of the question that contains information explaining what kind of information the question is trying to obtain. Alternatively, this basic help text can be turned on simply by clicking on the arrow next to the icon at the top right of the screen–this will activate the help text for whatever question you are currently typing in. To close this help screen, simply click on the arrow.

The PSAP also provides pop-up windows that lead to advanced help options throughout the assessment program. The Advanced Help guide can be accessed by clicking on the symbol next to each assessment question or by clicking on the hyperlinks for more information located in the basic help text. These boxes give users help in answering the content of the question. For example, if a user wanted to answer a question about the level of "vinegar syndrome" that a 16mm film was suffering from but did not know what vinegar syndrome was or how to assess it, he/she would click on the symbol next to the question for a popup that would explain what vinegar syndrome is, what causes it, and how to assess its level in a motion picture film. Many boxes also provide pictures to further help the user understand the concepts underpinning the question.

In summary, PSAP provides help by:

- explaining the assessment questions;

- explaining the concepts behind the questions;

- explaining how best to interpret your answer choices;

- providing images (where possible) to illustrate the concepts;

- minimizing subjectivity in the questions by giving you a practical sense of what the questions are looking for;

- providing educational resources to help understand the concepts and methods associated with item and collection preservation;

- providing recommendations, tips, and best practices so that you can improve the preservation practices in your own institution.

Supplemental Guides

Understanding Use of Certain Fields and Approaches in the PSAP

Preservation Assessments and Surveys

What are preservation assessments and surveys? Why do they matter?

Preservation assessments and surveys are a key element of good collection stewardship as they allow collection managers and curators to become more familiar with the condition of their collections and derive useful and accurate data about collections. This data helps managers to then establish and articulate preservation needs. In general, a preservation assessment considers many different facets of preservation need, ranging from the condition of specific materials to understanding how the building, environment, policies, and use all affect the health of the materials overall.

What’s the difference between the two?

Preservation Assessments: Most often, a preservation assessment evaluates the policies, practices, and conditions in an institution that affect the preservation of all or specific collections and considers the general state of the collections being evaluated, what is needed to improve that state, and how to preserve the collections long-term. It must identify specific preservation needs, recommend actions to meet those needs, and prioritize the recommended actions.

Typical components of a preservation assessment may include all or some of the following:

- Building/facility characteristics, including structure and maintenance;

- Environment of the building, including climate control, lighting, pests, housekeeping, fire protection, and security;

- Policies that affect preservation of collections, including emergency preparedness, disaster response, security, exhibit, circulation, and loan;

- Storage and exhibit areas, including shelving/case types and their condition as well as shelving and exhibit practices;

- Condition of the collection, either through a sample or item-level survey;

- Storage and handling practices, including use of protective enclosures, shelving practices, and staff handling;

- Reformatting and repair options available.

Preservation Surveys: By comparison, a preservation survey collects data on individual items to generate a broader understanding of the condition of materials. Therefore, preservation surveys are often incorporated into larger preservation assessments or provide information that can develop short or long-term preservation plans for collections or entire institutions.

Surveys may be one of two types:

- Condition surveys, which are designed to identify the physical condition of the collection in a specific manner, often combining observations on damage and deterioration with known use;

- Action surveys, which express the preservation needs of the collection in terms of actions that will secure, replace, protect, or treat the items examined.

Surveys can look at every item in a given collection, or at a sample of a larger collection. The PSAP (and AvSAP) can be utilized for both item-level and sample surveys (See sample versus item level assessment document for specifics on these two approaches and the benefits and drawbacks of each). From the information collected, survey data can be used to generate preservation priorities, which can be combined with collection/curatorial priorities as shown below to arrive at a prioritized approach to preservation action.

Preservation and Curatorial Priorities: An Example of Prioritization Outcomes

| High Use/Value | Moderate Use/Value | Low Use/Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Condition | VERY HIGH | HIGH | MEDIUM |

| Fair Condition | HIGH | MEDIUM | LOW |

| Good Condition | MEDIUM | LOW | VERY LOW |

Resources

- Brown, K. (2005). Use of General Preservation Assessments Process. Library Resources and Technical Services (LRTS), 49(2) April 2005: 90-106.

- Brown, K.E.K. (2006). Use of General Preservation Assessment Outputs. Library Resources and Technical Services (LRTS), 50(1), Jan 2006: 58-72.

- Buchanan, S., & Coleman, S. (1987). Deterioration Survey of the Stanford University Libraries Green Library Stack Collection. In P. Darling (Comp.) & Wesley Boomgaarden (Rev. Ed.), Preservation Planning Program Resource Notebook. Washington, DC: Assn. of Research Libraries, Office of Management Studies.

- Child, M. (1994). Preservation assessment and planning. In Preservation of Library and Archival Materials: A manual. Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center, 1994. Retrieved July 30, 2014 from: http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/1.-planning-and-prioritizing/1.2-preservation-assessment-and-planning

- Ogden, S. (1994). The Needs Assessment Survey. In Preservation of Library and Archival Materials: A manual. Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved July 30, 2014 from: http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/1.-planning-and-prioritizing/1.3-the-needs-assessment-survey

- Walker, G. (1985). The Yale Survey: A large-scale study of book deterioration in the Yale University Library. College and Research Libraries, 46 (March 1985): 111-132.

Assessing a Repository or Collection Using a Sample

The most diagnostic assessment option is an item-level assessment, in which each resource is individually assessed. Item-level assessment is recommended for either individuals or institutions with a small number of items or for institutions with enough staff and time for this type of thorough assessment.

An alternative approach to assessment is based on sampling. This is most useful for larger collections where item-level assessment would be too time-intensive. This method can be useful to help establish preservation priorities in a large collection, allowing you to strategically focus item-level assessments on the materials with the greatest need. A random sample assessment may also be useful to identify preservation needs for grant applications and other fund-raising efforts.

Item-level and collection-level assessments will produce different final products, though the reports will look similar in format. Although a random sample assessment will generate a final assessment report, it represents only a "snapshot" of preservation needs and priorities based on format and storage conditions. PSAP sample assessments can be done by one of two methods: a set percentage sample or a statistically valid random sample.

If your collection is large, you may consider doing a sample assessment, which can bbe approached in one of two ways:

- A Set Percentage by Collection

- A Statistically Valid Random Sample

A Set Percentage by Collection: To gather a very basic view of your materials, you can sample an identified percentage of the entire collection. We recommend a minimum of 10% of the total population of materials, or every tenth item. This method is particularly helpful if you don't know how many items you have. A set percentage sample will not provide detailed guidance on how many or which items need attention, but it will help prioritize preservation needs for the entire collection. You can then return to an item-level assessment for more detail or leverage your collection-level results to argue for preservation funding.

Creating a set percentage sample is relatively easy. If you want to end up with a 10% sample, you will assess every tenth item. If you want to end up with a 20% sample (which will be approximately twice as accurate as a 10% sample), you will sample every 5th item. The higher the percentage of your sample, the more accurate your results will be. Samples of less than 10% may give you a general idea of what your preservation needs are, but accuracy will be low and results should not be used for estimating specific project times or budgets.

A Statistically Valid Random Sample: A statistically valid random sample will give you estimated numbers of particular formats in your collections, their locations, and their prioritized preservation needs. This method requires that you know your total number of items to create a representative sample. You use either MS Excel or random number tables to select the sample. This provides more useful results because it commonly uses a larger sample than a set percentage sample. It requires more work to set up than a set assessment sample, but it is far less time consuming than a full item-level assessment.

Creating a random sample is slightly more complicated. First, you establish the total number of items in your collection (or the portion of your collections that you wish to survey). This is called your "population." You then choose what level of accuracy you want from your results. Accuracy is measured in two ways: "confidence" and "tolerance/margin of error." Confidence is a measurement of accuracy based on the repeatability of the sample. If you choose a confidence of 90% and you repeat the sample 100 times using a different randomly selected sample, your results would be the same 90 of those 100 times. Recommended confidence levels for sampling a collection are 90, 95, and 99 percent. Ninety-five percent is usually the optimum confidence level for accuracy of results and manageability of sample size. Tolerance or margin of error is the threshold of error that you allow for your results. For example, if your sample tells you that 80% of your collection consists of VHS tapes and you have set your margin of error to plus or minus 5 percent (±5%), then your collection might have between 75-85% VHS tapes. Common tolerance thresholds are ±2 or ±5 percent.

When you combine confidence and tolerance, you get the overall accuracy of your sampling results. For a sample that results in 95% confidence with a tolerance of ±2%, you would know that in 95% of the times you repeated the survey, the number of occurrences (of any one format or identified level of deterioration, etc.) would be accurate 95 out of 100 times within a range of ±2 percent. Once you have selected your desired confidence and tolerance, you use these values to determine the sample size of your overall population. Many web applications can do this for you, and a simple search for "sample size calculator" will likely yield several. One of our current favorites is the Raosoft Sample Size Calculator available at http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html. Simply enter values for margin of error, confidence level, and collection size, and the calculator will calculate how many items you need to sample. In a collection of 5,000 items with confidence set at 95% and tolerance set at ±2%, your sample size would be 1,623 items. For a confidence and tolerance of 90% and ±5% (much less accurate but still valid for many purposes), your sample size need only be 257 items. Finally, you must determine which items of your collection you are going to sample. To make a sample statistically valid, items must be drawn from your collection RANDOMLY. Random numbers can be generated through Microsoft Excel, a web-based random number generator, or a published book of random number tables. [Note: numbers generated through Excel or a web based number generator use a complex mathematical algorithm, which to a statistician is not truly random. However, they are considered 'nearly random,' which works just fine for our purposes.]

If all of your materials are combined in one area and can be assessed linearly, selecting a random sample is straightforward. A list of random numbers between one and the total size of your collection can be generated, and items matching the random numbers are pulled for the sample. However, this method is less straightforward for multiple archival collections spread among different locations. If this is your situation, you can randomly select both a collection number and an item number or even randomly select collection, box, and item number. For example: if you have 50 collections that have materials to be assessed, each collection has a maximum of 200 boxes, and each box contains a maximum of 100 items, you can generate three random number lists and work down all three lists in tandem. To generate your random numbers, you would require three lists of random numbers: one of numbers 1-50 for the collections, one of numbers 1-200 for the boxes, and one of numbers 1-100 for the items. It is recommended that you have at least double the number of random numbers in each list as the size of your sample. So, if your sample size was 257 items, each list should have about 500 random numbers between the defined range.

Understanding Significance

The PSAP recognizes that an item or collection's informational content can--and sometimes should--be taken into account when generating a prioritized preservation plan. In the PSAP application, significance is either selected or it is not, there is no scale of significance or option for indicating what type of significance is associated with a resource. Choosing a level of significance in this question will not affect the overall score of the resource. It can, however, allow you to rank your decision list by significance should you choose to. Consider this question as a way to flag significant materials in your decision list. If you have a resource item or collection that is in poor physical condition but has little significance to your institution, you may choose to put it lower on your prioritized list than a resource in better physical condition that has greater significance to your institution. For this reason, PSAP can factor this added nuance into its results through an evaluation of a resource's 'significance'.

While this field is optional, we recommend you consider the significance of the item as it will affect your preservation decisions, particularly when you have a limited amount of funds and a great deal of materials to treat. Of course, you may also exclude this consideration if you wish. This is the best choice for users that only have interest in the physical condition of the items you are assessing, without respect to the informational content of the materials.

For our purposes, we break down the concept of "significance" according to traditional archival theory:

- Significance of the item/collection to your institution and its mission

- Significance of the item/collection to your users

- Contribution of the item to scholarship

- Uniqueness of the item/collection. (Uniqueness in this context refers to how many copies exist. Commercially produced materials are not usually considered unique. An example of an unique item would be a handwritten document, since it is unlikely that there are many copies of this item.)

- Costs of retention, or how much it would cost you (in terms of space, funds, and time) to maintain, store, and provide access to the item

- Importance of the events, people, or subjects related to the item/collection

- Political considerations involved in retaining the resource, such as the importance to your community, a donor, or the creator of the item/collection

These are just some of the factors you can consider when making decisions about the significance of an item or collection. Some institutions may consider the fiscal value of a resource as well, which is usually determined by an outside (third party) appraiser. Assigning a high level of significance to most or all of your materials will render this field worthless in your final decision list. For this reason, we strongly recommend for you to be as discerning as possible when assigning a level of significance to your materials.

Understanding Dates

Assigning dates to resources can be a tricky process, because it is often difficult to determine whether the date value should be the date the resource was created, the creation date of the items the resource contains (if it is a collection of items), the date of the original resource (if it is a digital version or facsimile), or the copyright date (usually in the case of a book). For the purposes of the PSAP, date values should represent the creation of the physical resources. This is important in determining the preservation risks to the physical material.

If you are interested in finding out more about describing archives resources, see the Society of American Archivists' Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS).

Entering Dates

The date value follows the YYYY-MM-DD syntax, and comes in three different forms (types):

Single date: Resource falls within a single year or has an exact date (e.g. "1987" or "1987-02-27")

Span/Inclusive range: Resource spans across a range of dates: the earliest and latest dates (e.g. Begin: "1987"; End: "2014")

Bulk range: Resource has a predominant focus in this date range; must be used to complement a span/inclusive date range (e.g. Begin: "1987"; End: "2014")

If the full date is unknown, month and year (YYYY-MM) or just year (YYYY) may be used.

Use Cases

- My resource is a single, hand-colored, silver gelatin print. This is one of several prints produced from a negative. The polyester negative was produced in 1957, but the print being assessed was produced in 1981.

- During assessment, the date assigned to this resource should be a single date of 1981, because that is the date that represents the material components of the print.

- My resource is a compact disc created in 2010 containing files originally created in 1985.

- For the purposes of the PSAP assessment, the date assigned to this resource should be a single date of 2010 because that is the creation date of the physical item. The PSAP is not designed to comprehensively address digital content; and while issues like file format obsolescence may affect the resource, that is outside the scope of the PSAP assessment.

- My resource is a collection of documents accessioned after the retirement of a faculty member, which were created throughout her many years at my institution from 1975-2005. However, the vast majority of the documents were created between 1999 and 2001.

- In this instance, the resource should be assigned a span/inclusive range of Begin: "1975"; End: "2005". Additionally, it could be assigned a bulk range of Begin: "1999"; End: "2001".

- My resource is printed ephemera, and I have no idea what the date of creation is.

- In this case, try using the Collection ID Guide to determine the general time frame that the resource could have been produced. If no date can be determined, you may leave the date field blank and continue to assess the resource without it.

Understanding Institutional Practices

Preservation Planning

A preservation plan is a document that addresses the overarching preservation needs and approaches for the collection(s) in your care and considers what steps the institution must take to address these needs with the resources it has available or means to acquire. A plan should not only address the value of materials—where value may be monetary, curatorial, rarity, etcetera, or any combination of these—but should also encompass all of the institution's collections to some extent, while prioritizing based on preservation need and value to the institution/collection. Preservation plans should be living documents, which grow and adapt over time as collections are added to the institution and institutional priorities change. Revision should occur every few years to accommodate accomplished goals and changing priorities and opportunities.

The PSAP can help with the formation of a preservation plan by giving you a deeper understanding of what collection materials are most at risk and, therefore, which collections require the most pressing preservation attention.

A preservation plan should describe the current state of a preservation program/initiative or the lack thereof. It should acknowledge support and interest in furthering preservation efforts, and it should clearly outline prioritized preservation needs and available resources, policies, and operations that support those needs. Specifically, a primary purpose of the preservation plan is to establish both short and long-term goals for the development of a preservation program/initiative. These goals should be prioritized for implementation in some manner, often by those obtainable with current staff and funding followed by those only obtainable with additional support—either through reallocated internal resources or external sources, such as grant funding.

Format-specific Preservation Plans

It may be useful to consider tailoring preservation plans or portions of a larger preservation plan towards certain formats in a collection(s) to develop preservation progress in a certain area. Audiovisual materials especially may benefit by this approach because of their unique fragility and susceptibility to obsolescence. The PSAP can help you assess the AV materials in your collections so that you can make informed and targeted decisions in terms of what to conserve and reformat, and when. Similarly, early photographic materials or fragile reprographic processes may be evaluated using the PSAP to guide collection managers in setting meaningful goals for the preservation of these often unique or near unique collection materials.

Resources

- Dean, J.F. (1995). Managing collection information for preservation planning. In Advances in Preservation and Access, Volume 2. Bedford, NJ: Learned Information, Inc.

- Ogden, S. (1994). What is preservation planning?. In Preservation of Library and Archival Materials: A manual. Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved July 30, 2014 from: http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/1.-planning-and-prioritizing/1.1-what-is-preservation-planning

Environmental Guidelines

Climate Control

The physical environment—and the ability to control it—should be the highest priority of any collecting organization. This encompasses balanced temperature and humidity, regulated light sources, clean and well-circulated air, and preventive measures against pest infestation and water exposure. An HVAC (heating, ventilating, and air conditioning) system the ideal mechanism for much of this, and is most cost-effective with regard to long-term preservation. But HVAC installation and repairs can be very expensive—perhaps too much for some organizations. See Control Mechanisms below for more.

Regardless of an organization’s financial resources, one can easily monitor and even manage environmental conditions with even a the most modest budget. The work that you put into your building’s envelope and climate control mechanisms has a direct and significant impact on the life-long health of your collection materials. With this in mind, always strive to maintain communicative relationships with your facilities and maintenance staff. Convert them to the preservation way of thinking whenever possible.

See the sections below and Exhibition Guidelines for practical steps to improve both macro- and micro-environments. If nothing else, try to keep most collection materials in an environment that most people would be comfortable in (65–68°F). But, of course, a colder and drier climate is almost always an improvement, so this means moving your materials out of the hot attic and the damp basement, if possible.

Environmental Monitoring

A monitoring program will allow you to establish a baseline for your environment and its typical conditions. From this data you can infer deterioration rates of your collection materials, the risk of mold outbreak, and likelihood of pest infestations. As a result, your organization will benefit from having hard data to improve policy and environment control measures. Environmental monitoring is the single most important thing you can do to sustain the life of your collections.

A full-scale environmental monitoring program should be comprehensive, including:

- Temperature: Establish an average temperature and the allowable annual variance.

- Relative Humidity (RH): Establish an average relative humidity and the allowable annual variance (RH is the amount of moisture [water vapor] held in the air, expressed as a percentage of the maximum amount that the air could hold at the given temperature).

- Pest Populations: The goal is not to eradicate all pests. Instead, integrated pest management (IPM) can be your first line of defense (see Mold/Pests below). Establish a normal, healthy range for your facilities throughout the calendar year and then continue to monitor fluctuations to make targeted adjustments.

Other environmental considerations include:

- Light Levels (visible light and UV light): Monitoring light levels (daylight and artificial lighting) will not necessarily be a sustained action (unlike temp., RH, pests), but results should be considered each time collections are shifted to a new environment (e.g. exhibitions).

- Pollution Levels: Monitoring contaminants is a relative rarity; valid pollutant monitoring requires gas analyzers and other expensive gear. Instead one can make sure that HVAC system’s filters are changed often to mitigate the effects of airborne pollutants.

Monitoring Equipment

The quality and prices of equipment varies considerably. Though some tools have emerged as the industry standard for a given function (i.e. PEM dataloggers), keep in mind that any one of these methods below will be effective so long as you are checking and recording results consistently.

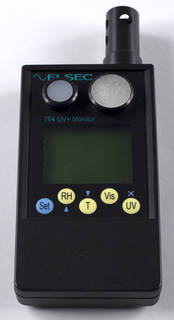

Temperature and Relative Humidity

- Datalogger

- Hygrothermograph

- Portable hygro-thermometer

Pests

- Traps (sticky and non-toxic)

- Temperature and RH monitoring should inform prevention of mold and pest population growth

Light

- Light meters

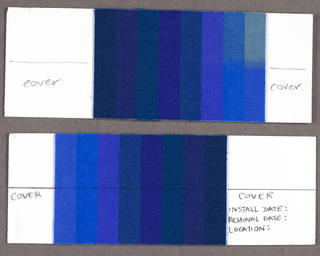

- Blue Wool test

More than high-end equipment, trained and attentive staff will go a long way in the effort to monitor across facilities and across collections spaces. Getting people to recognize the importance of a balanced and well-documented environment is the most crucial first step.

Temperature

Regulating temperature (along with humidity) is crucial for lengthening the viable lives of your collections. High temperatures will accelerate the rate of material deterioration. All damaging environmental factors are exacerbated by heat and humidity, including inherent internal flaws (residual chemicals) and external threats (air pollutants) alike. For example, photographic emulsions, prints, and writing media will oxidize more quickly, color dyes will fade more drastically, and acidic papers will yellow and embrittle at accelerated rates.

Temperature and humidity will have a mutual effect on one another. "Within certain ranges, a lower temperature can compensate for a higher RH and vice versa" (Roosa, 2002). The preservation community recognizes this (see ISO 18911; Image Permanence Institute), and, in lieu of recommending rigid temperature and RH limits, has championed target storage climate options. For example, at a cool-moderate temperature, the RH range may be 20–30%, while freezing conditions could allow for a broader range between 20–40% or more broad, depending on the materials.

Variations in temperature can cause your materials to expand and contract which can age these materials over time. It is best to keep temperatures in your facilities as steady as possible so as to lengthen the viable lives of these items. Even if you cannot maintain the ideal storage temperatures for your materials, it is still helpful to minimize the variances as much as you can.

| > 72°F (> 22°C) | Warm – Hot (Poor) |

| 65–72°F (18–22°C) | Moderate (Room Temp.) |

| 55–65°F (13–18°C) | Cool |

| 32–55°F (0–13°C) | Cold |

| < 32°F (< 0°C) | Freezing |

Remember that optimal temperature ranges are just that: ideals. They might not reflect what you are able to accomplish in your storage facilities, but the closer you can get to these conditions the better. Keep in mind that variations in temperature are what we are really trying to avoid. Keeping your materials at steady temperatures, even if imperfect, will still help grant them longer life. You should also consider how to arrange your collections. Since different formats have different needs you may consider how you can store them separately so as to properly match an item with an environment. Don't be discouraged! These conditions should be the goal that you are moving toward, even if you can't always achieve them. For more specific environmental conditions based on formats, see the respective profiles in the Collection ID Guide.

Humidity

Extreme highs, extreme lows, and fluctuating humidity will have a negative effect on materials. Relative humidity (RH) is a measure of how saturated the air is in an environment.

- A high RH will generally cause materials to swell and misshapen, as well as make conditions favorable for pest and mold growth/damage.

- A low RH often causes materials to desiccate, shrink, crack, and curl.

- RH fluctuation beyond 10% above or below a set point begins to put materials under considerable strain and at great risk, as the components will often react incongruently (e.g. photographic support and emulsion contracting and expanding at different rates).

As with temperature, rapid fluctuation is the real threat, speeding up chemical deterioration and bringing stress to collection materials over time. It is best to keep the humidity across your facilities as steady as possible. Even if you cannot maintain the best possible relative humidity levels for your materials, it is still helpful to minimize the variances as much as you can.

Generally, it is best to keep collections between 30% and 50% relative humidity. It is important to remember, however, that often when you lower the temperature, you raise the relative humidity. This is why it is critical to monitor humidity and temperature in your storage facilities. Bringing materials out of uncontrolled environments like basements, sheds, and attics and moving them into climate controlled areas like internal rooms or even closets can do much to keep these materials viable.

| < 20% RH | Extremely dry (poor) |

| 20–30% RH | Low humidity; dry (acceptable) |

| 30–50% RH | Moderate humidity; temperate (excellent) |

| 50–70% RH | High humidity; humid (poor) |

| > 70% RH | Extremely damp (very poor) |

| ± 5% RH | No risk |

| ± 10% RH | Minimal risk |

| ± 20% RH | Moderate risk |

| ± 40% RH | High risk |

Control Mechanisms: Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning

The best thing you can do to protect from seasonal shifts, pollutants, and particulate matter is to have a dependable heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system in place. Filtration, AC, and dehumidification running on a 24-hour-a-day cycle will do more in the long run to protect items in your care than any high-end airtight enclosure could. In addition to regulating temperature and humidity, a modern HVAC system should also filter particulate matter from the environment. Just remember to change filters on a regular basis.

For many however, the cost of purchase and installation of an HVAC system in an existing space is prohibitively expensive. Room-size air conditioning units may be an achievable alternative. Temperature control will make relative humidity more easily manageable. If air conditioning is not an option, strategic placement of fans and dehumidifiers are a workable substitute to mitigate extreme temperature and humidity in your space. Do not open windows, however, as this would allow unfiltered contaminants and organisms into the environment.

| Temperature | 65–68°F (±2°) |

|---|---|

| Relative Humidity | 45–55% RH (±5%) |

Also consider the strength of your microclimates. If possible, do not place your collection materials near the window, against exterior walls, or on/near the ground. A well-sealed case can be a decent buffer from humidity and accidental leaks or spills. In seasons or geographic regions of high humidity, silica gel (or similar desiccants and humectants) can act to keep humidity at acceptable levels by absorbing moisture in these more enclosed areas. Contact a supplier or manufacturer to learn more about what your unique environment will necessitate.

To learn more about environmental control practices with regard to collection storage, see the Image Permanence Institute’s Environmental Management research and publications.

Mold and Other Pests

High temperature and humidity also heighten the potential for mold growth. Once mold takes hold of materials, especially photographic materials, it is nearly impossible to remove without permanent damage to the visual information. It is best to stay well below 60% RH and below 75°F in order to prevent mold and fungi outbreaks.

Insects and rodents, in one form or another, will undoubtedly exist in comfortable climate controlled environments. The first thing you must do is accept this—learn to look beyond the errant mouse or cockroach to see their occasional presence as normal. For the sake of collections and personal health, consider a defense alternative to fumigation and the use of harmful chemicals.

Integrated pest management (IPM) is a proactive method designed to pinpoint potential pest infestation areas and to determine whether there are facilities maintenance or operation issues that need to be improved to reduce the likelihood of a full infestation in the future. This approach essentially treats pests as symptoms of greater environmental control shortcomings (e.g. compromised building envelope, policies, HVAC system failure).

Although the process may take 1–2 years to establish, you can determine acceptable insect levels to anticipate season-by-season patterns by monitoring pest populations across the most sensitive areas of your facilities. Once a baseline has been set, staff might then be able to point to sharp upticks in a particular area and thus make a strong case (with hard data) for more meaningful and lasting repairs.

For more information, see Museum Pests by the Integrated Pest Management Working Group (IPM-WG) and the University of Illinois Library Preservation’s Integrated Pest Management program.

Light Levels

Light exposure is the primary external threat to objects on that are on display (see Exhibition Guidelines). Exposure at any level is a threat, but a high level of intensity (e.g. natural light) at long intervals will be most immediately damaging. The effects of light exposure are cumulative: short-term exposures at low intensity can add up to affect significant damage to an object. And because this fading is gradual, it is often difficult to recognize before it is too late.

Light damage is irreversible. Exposure will cause surface discoloration and severe fading that in most cases cannot be repaired. For paper, light can also weaken the internal structure, weakening and embrittling its support. All photographic materials are highly susceptible to light damage, especially color dye images. Many printing inks, writing and drawing media can altogether fade to nothing.

Measuring Light Levels

Light level measurement can range from the highly precise (and expensive) to low tech (and low cost), and there are many practical workarounds. On the high end: light meters measure visible light, while UV meters (more expensive) measure invisible UV radiation. If a UV meter cannot be procured, it is safe to assume sunlight, fluorescents, and halogen lamps will produce high UV radiation and will necessitate filters (Conn, 2012).

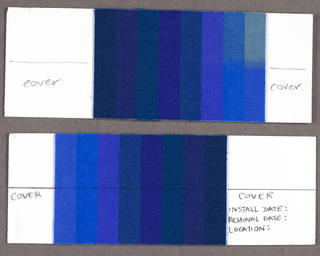

Another method of measuring light is through the use of Blue Wool tests, which demonstrate light damage to an array of blue-dye colourants in wool samples. By observing dye fade from exposure to a given light level for a specific length of time, you can gain an idea of appropriate exhibition intervals—or convince others at your institution that endless exhibitions are in fact damaging your collections. ISO’s Blue Wool cards are available from many archive material suppliers.

Many SLR film cameras and some DSLR (digital) cameras have built-in light meters capable of measuring light levels in a "scene." Though the quality of through-the-lens light metering will vary, most will help to provide you with a scale of high and low intensities in your space. Ultimately, for many institutions, these light readings do not necessarily have to be exact. As is the case for many quick-and-dirty methods, you will learn that doing something—however small—is better than nothing at all; use the tools at your disposal to make the most informed decisions possible.

Gaseous Pollutants and Particulate Matter

Airborne pollutants initiate chemical reactions that may stain and degrade support or base materials. They can also accelerate the fading, staining, or loss of photographic and print/writing media (e.g. sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and ozone cause oxidation in silver images and contribute to silver mirroring or yellowing).

Sources of pollution can include:

- Emissions from the facilities

- Facilities cleaning chemicals

- Furniture and decor materials (e.g. rugs, window curtains)

- Environmental systems

- Office equipment

- Collection materials

- High traffic (people)

- Other external sources

Gaseous pollutants include sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone, acidic fumes, ammonia, and peroxides, just to name a few. Particulate contaminants are very fine solid or liquid particles that may lead to the soiling and abrasion of material surfaces. Particulates can include dirt, aerosols, and dust, the last of which (i.e. dust consisting of human skin, fibers, pollen) may also attract pests. Particulate matter are most easily removed from the environment by filtration systems. Most HVAC systems and furnaces have filters that help to mitigate the effects of airborne pollutants; these will need to be changed regularly.

Water Exposure

Water damage, irrespective of the cause, can cause:

- Paper staining

- Aqueous coloring/colorant bleeding,

- Coated papers and photographic materials alike to block or stick together,

- Photo emulsion to delaminate,

- Pest populations to rise, and

- Rapid mold growth.

Water damage can be minimized with the appropriate disaster planning and response infrastructures in place. See Disaster Preparedness for more information.

Resources

- Conn, D. (2012). Environment: Protection from light damage. Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved from: http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/2.-the-environment/2.4-protection-from-light-damage

- ISO. (2000). 18911 Imaging materials–Processed safety photographic films–Storage practices. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

- Roosa, M. (2002). Care, handling, and storage of photographs. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core Programme Preservation and Conservation.

Use and Access

Control, organization, and documentation will not only keep your collections safe, but will improve long-term accessibility into the future. Policies and regulations like those outlined below that establish levels of access and use are a great start to safe-guarding collections.

Handling and Collections Care

One of the easiest areas to implement protections for collections is through careful handling and sensible collections care. The unfettered use and handling of materials heightens the general risk of damage--be it through neglectful handling (e.g. touching photo emulsion with bare hands) or irresponsible operation of access equipment. Whether intentional or not, this is a risk posed by patrons and staff alike.

Examples of neglect, mishandling, and mismanagement include:

- Pressure-sensitive (such as “Scotch®” brand) tape to mend tears.

- Permanent or volatile inks used to label documents (even the back side).

- Folding materials to fit into a given box or enclosure.

- Poor handling: Not washing and drying hands before handling fragile documents; or not using gloves when handling materials that could be damaged by contact with oils on the skin (for example: gloves must always be worn when handling metals).

- Inadequate storage or exhibit environments, such as areas with excessive climate swings or the use of poor display mounts.

- Inadequate packaging/padding for shipping

- Lack of bibliographic control over holdings, which has led to the harmful and excessive use of unique or vulnerable items.

General Recommendations:

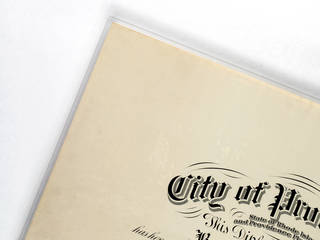

- Use archival-quality folders, boxes, sleeves, and other enclosures to support and house materials of differing shapes and sizes. Avoid use of acidic containers such as brown paper bags and shipping or moving boxes.

- Use only Photographic Activity Test (PAT)-compliant storage enclosure materials for valuable photographic materials.

- Wear gloves (either cotton or nitrile) while handling archival photographic emulsion materials and museum objects.

- Avoid wearing cotton gloves while handling particularly fragile or slippery items, since gloves can hamper tactile senses and lead to accidentally dropping and breaking objects.

- Handle fragile materials as little as possible.

- Use clean, dry hands with carefully trimmed nails to handle materials (even when wearing gloves).

- Use both hands and ask for assistance when handling/moving oversized materials.

- Remove jewelry and accessories, including anything hanging around the neck or clothes that may inadvertently come into contact with and damage materials, such as: necklaces, headphones, glasses hanging around the neck, nametags, scarves, rings, watches, bracelets, ties, loose sleeves, and belts. Avoid wearing loose clothing.

- During transport, use enclosures, supports, book carts, and other equipment as appropriate to minimize the risk to materials. Use materials like foam and snake supports to ensure that items are supported and do not come in contact with other items or with the sides of carts during transport. Always ensure sufficient assistance while transporting items.

- Only use pencils for direct labeling (e.g. on a photo verso) of paper, AV, and photographic materials or folders/enclosures. Never use or carry pens around items and materials.

- Ensure that patrons know and understand guidelines on proper handling of all fragile materials.

- Ensure that staff, volunteers, and patrons are adequately trained in handling collection materials.

Cataloging and Description

An undocumented or poorly described collection can be especially vulnerable to theft, neglect, deterioration, improper storage, and deaccessioning. Although collecting institutions typically create formalized inventory controls and finding aids when an item/collection is accessioned, these accession records may not be authoritative, descriptive, or publicly searchable.

Why Is Description Critical to Collection Management?

- Why Is Description Critical to Collection Management?

- Without descriptive data capturing key characteristics, all materials are at greater risk of misidentification, misplacement, and improper care.

- Digital files are especially vulnerable to loss without descriptive data. These items cannot be visually browsed or skimmed like photos and other human-readable documents. Instead, the information is retrievable only through machines.

- Descriptive information makes digital and analog materials searchable for administrative and collection development purposes, and helps makes items easier to access for researchers.

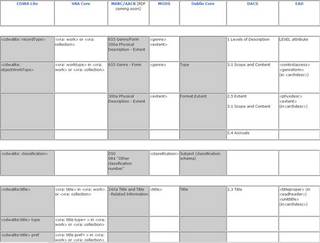

- At a minimum, in order to make analog or digital items searchable, it is important to collect information about the materials. Information such as a unique identifier, title, creator, date, format, collection size, access restrictions, and use restrictions (e.g. those based on intellectual property and copyright issues) are key elements for promoting and aiding access to your holdings. At the very minimum, you should consider documenting this information. To best ensure the longevity and use of the information, it is also a very good idea to describe the collection or item using a common, well-known metadata standard (e.g. Dublin Core). For more information on descriptive metadata, refer to the Understanding Metadata section in this User Manual.

Originals and Copies