Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Film

Unique Content

If what you are assessing is a commercially produced item, more than likely it is not "unique." It may be unique to your archive but, at some point, it was mass produced. Truly unique items often require priority in preservation because they may be the sole remaining document of this material.

First Generation / Master / Original Items

When we talk about "generations" in audiovisual preservation, we're talking about "copies." If something is a second-generation item, it means that it has been copied from the original, or "master." (We should note that sometimes people use the term "master copy," which can be confusing. A master copy is a master.)

The original audiovisual item is the most valuable iteration of the item that you can have because it should have the best audio and video quality possible when compared to its copies. (This assumes, of course, that the original has been well preserved and is in good shape.) Another reason for giving priority to the original is that it may be the only iteration there is of the item. This means that any damage that occurs to the original could mean that information is lost forever. Even if you have a copy, damage to the master means that you must resort to using copies that may have inferior picture and/or sound.

Following best practice, you should use the master as little as possible and store it in the best conditions possible. Many institutions use their master once to make a "secondary master." This secondary master is then used to make copies for access. Ideally, you should almost never have to return to the master so that it can stay in the best possible storage conditions in perpetuity. If the item you are assessing is a master, then it will be higher in priority for reformatting and preservation than those items which are copies.

In the case of film, your collection may contain many copies or iterations of the same film. These various film elements could be original negatives or positives used to create the master print. For example, 16mm film that has been acquired from a film maker could be labeled as A and B rolls. These elements are original positive or negative images used to create the final master print. Additionally, there may be a sound track element on a separate roll of film. This combination of A, B, and soundtrack rolls comprise the whole of the final film print. It is important to keep these elements together (at least, intellectually) as they are original materials and may be used in the future to reprint the entire film.

It is especially important to note if a film is reversal. Reversal film is the original film that runs through the camera and is then processed into a final projection print. Thus, the camera original and projected film are the same. If this film has not been duplicated, you are running the risk of losing what may be the only copy if this film is damaged.

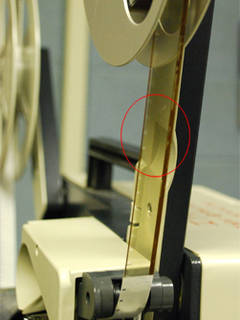

Playback

Playback and handling are the leading causes of damage to audiovisual items. A film, for example, is most likely to be damaged being fed into or coming off of a projector. Any playback machine, no matter how well maintained, can cause damage to an audiovisual item. That said, it is still best to maintain your playback equipment alongside your audiovisual items. Regular service and cleaning is critical to helping minimize the risks of playback for your materials. An item may sometimes only have one play left before it is permanently damaged, rendering it unusable. If an item must be played back, an operator skilled in handling the playback equipment and at identifying problems with the media prior to playback should be the only person allowed to play the material in question. Allowing media to be handled and played back by untrained staff or patrons is a danger to the material.

Playback Equipment

One of the great challenges of audiovisual preservation is the fact that AV materials require playback machines in order to "decode" the information stored on the materials. This applies to all audiovisual formats. Of course, a further complication is that the playback machine must be appropriate to the format of the AV material. When we consider how many hundreds of AV formats there are, we see that this is a large challenge indeed. The playback machine must also be well-maintained because it can damage the materials fed into it if the machine is in poor repair.

It is important to look at your collection and consider what formats are most valuable to your institution, what formats are accessed the most by your users, and what format you have the most of. These will be the materials for which you should have playback equipment, if at all possible. This can be challenging, but there are avenues you can explore. Local television and radio stations, colleges and universities (particularly those with film, art, communications, or journalism departments), and audio recording studios often have older equipment that they no longer need. As a result, these are excellent places to establish relationships with as you may be able to procure equipment at very reasonable prices. However, keep in mind that universities and colleges often have considerable red tape when selling or donating their equipment, so you should be prepared to invest some time and effort when working with them.

Remember: never put any collections materials into a playback machine without first testing that machine. Have a "dummy" item that you can test a piece of equipment with. For example, you can designate a VHS tape as your dummy tape and use it to test your recently procured and/or serviced VCR. Ideally, this tape should neither be an item that is a part of your collection nor have any value so that it will make no difference if you damage the item.

We do not recommend that you service a piece of playback equipment yourself because of the potential for damage to both the equipment and AV materials. We recommend that you find and establish a relationship with a local repair service. Maintaining your playback equipment should be at least as important as maintaining your collections.

If you do not have (and cannot acquire) playback equipment, it does not mean that the AV materials are without value. In fact, it may be an indicator of higher preservation priority if the playback equipment is obsolete or unavailable to you at your archives. These materials can be especially vulnerable. Film duplication vendors will most likely have the equipment and can transfer the film to a format accessible to your archives.

Remember, if you have materials with no way to play them back, these items will have diminished accessibility. They can end up costing you time, effort, and money when you have to send them out to be transferred to a format for which your institution does have playback equipment. If you plan to digitize your materials, you will have to have well-functioning playback equipment for each format you decide to digitize.

Orientation in Storage

Film should be stored by stacking film canisters horizontally on a shelf. Film that has been stored over time in different orientations has an increased preservation priority.

Film is heavy! Because of its weight and the way that it is wound, it is best to store film flat and on an inert plastic core. Doing so will allow the film to keep an even, rounded shape. Stacking film on reels without a film canister of some kind is not recommended because the reels will, over time, be compressed and can press into the film itself.

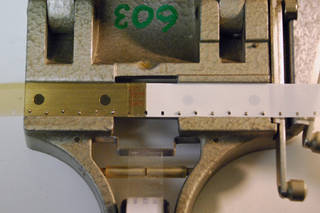

Film - Storage Container

Appropriate film containers:

- Protect the film from damage, dust, and other contaminants

- Will not exacerbate film deterioration. Dirty, rusty, non-vented, and dented metal containers can heighten the potential for film surface damage

- A good canister allows a film to "breathe"; that is, the canister is vented to allow for air exchange, particularly in the case of acetate films

Ideally, motion picture film should be stored in vented plastic cans. Film stored in metal containers or stored without a container will have a higher preservation priority.

Film without a container is especially vulnerable to damage or contamination through surface scratching, unwinding, dust, and mold. Yet, simply storing your film in a container is not enough. If your film is stored in a rusty, dirty container, it is not receiving adequate protection. Dirt and rust flakes can scratch the delicate film surface. You should consider replacing damaged containers in order to increase the longevity of your film.

Containers are made from a variety of materials: inert plastics, non-corrosive metal, and cardboard. The container your institution uses will largely depend upon the film storage environment. Are you storing your film in a standard room-temperature environment? Are they stored in a freezer? If you are storing your film in a room-temperature environment, polypropylene or polyethylene containers that are vented are optimal. This will allow for the film to "breathe" and to off-gas vapors that may be emitted from the film. If you are storing your film in freezing temperatures, your cans should be sealed and moisture-resistant. In all cases, cans should be clean and free from debris, rust, and structural damage.

When freezing film, ensure that the the film is properly housed by double-bagging it in zip-sealed freezer bags. If you are interested in freezing infrequently accessed materials, see the Home Film Preservation Guide for detailed steps on how prepare your film for long-term freezing.

Cores

Ideally, films should be stored on cores, not on reels. Films that are stored on reels or that are stored with neither reel nor core are considered higher preservation priorities.

A core is distinct from a reel. A reel is a metal or plastic hub with extended sides between which the film is wound for projection. Reels—especially metal, dented, or otherwise damaged reels—are NOT appropriate for long-term storage.

These cores should be made of an inert plastic material. For 16mm and 35mm film, the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) recommends that the core be at least three inches wide. A larger core diameter lessens the stress on the film because the film does not have to wind as tightly around a larger core as it would with a small core. Smaller gauge film may be wound on smaller (less than 3") cores.

Labeling

If your item has any kind of labeling on the container, the item itself, or any related material, we highly recommend that you revise the description of this item and enter this information in the notes field.

If correct, the labeling on a container or leader can offer important clues about what is on the film. If you are replacing a container or leader that holds labeling information, it is important to transfer this information to the new container or label. Be sure to copy down any titles, dates, or production data found on these items; and, save notes housed on the can. Information gained from container labels should be used with caution as cans frequently are reused or switched by accident.

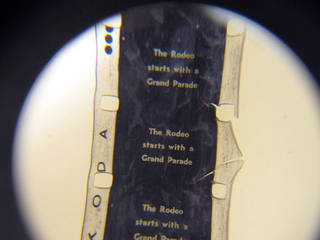

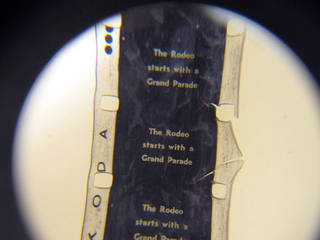

Film Leader

It's easy to tell if a film has leader. Look at the outer layers of the film. Leader is usually white, yellow, or clear, and it often has writing on it (but not always). The writing could be the name of the film, the filmmaker, etc. A film without leader is at greater risk for damage and dust contamination. Consequently, a film without leader will have a higher preservation priority.

Leader can be made of white or clean polyester film stock or from unprocessed black-and-white print stock. It is usually attached to the beginning or end of a film, but in some cases, it can be spliced between shorter films to separate individual films on a single reel. Some preservationists prefer using different color leader for the beginning ("head") and the end ("tail") of the film. Leader is used to protect the film and can also be a place where pertinent information about a film can be written. As projected film is most likely to be damaged at the beginning and end of the film, leader should be fairly long (i.e. enough leader to wrap around the reel a few times) so that there is sufficient leader to protect the film at the head and the tail. In this way, the leader would take the brunt of the damage if there were any issues with the projector feed. Damaged leader is easier to replace than unique film frames. Dirty or damaged leaders should be removed and replaced. If replacing leader that contains information, transcribe that information onto the new leader.

Film Damage

This question may involve unspooling the film to answer. Unspooling film is not without risk. If you are unable or unwilling to unspool your film and you have no supporting information that may answer this question, we recommend you click on "Unsure."

Motion picture film can be very long-lived when stored properly. That said, it can also be a very fragile medium. Film that is damaged even slightly can be damaged even more during playback. PSAP considers damaged film to be at higher risk.

Film damage can include scratches, torn sprocket holes, and torn film. It is absolutely critical to inspect film before playing it back. Projectors put film under great amounts of torque and that force can cause small tears to be full breaks. Film that has even minor tears (particularly to the sprocket holes) can be irreparably shredded during projection.

Ideally, a user should unspool a film on rewinds before projecting or sending off for transfer to video (telecine). Carefully inspect the sprocket holes as you wind through the film. Take a look at splices and make sure they are still intact. Make sure that the film is all in one piece—many times small pieces of film will be wound in a reel and will need to either be spliced into the larger film or removed and wound onto their own cores.

When you unspool your film be sure to note what kinds of damage the film is suffering from and, ideally, where on the film (in terms of feet) the damage occurs. This information should be recorded in the finding aid or catalog entry for this film. If you are sending this film out for repair and/or transfer work, be sure to pass this information on to them.

Mold / Pest Damage

The gelatin binder of photographic film is an especially good nutrient for mold. If your film is exhibiting white or brown patches or if you see a lattice-like growth on the edges of the film, you are most likely viewing mold. Film stored in hot, humid environments (generally above 65% relative humidity) is most vulnerable to mold, mildew and fungus contamination. Mold typically damages the edges of a film first. If mold has eaten into the emulsion, the film will be noticeably and irreparably damaged, exhibiting feathery-like distortions or dull spots on the projected image. Mold on film can be removed through cleaning and then storing the film in a cold, dry environment.

Pests like insects and rodents tend to like paper and textile materials more than film-based materials. That said, pests can still do damage to your AV collections. Insects can be attracted to the organic components of film emulsion, although film cans, both plastic and metal, tend to keep most pests out. When assessing the exposure of your collections to pests, it is necessary to look not just at the materials themselves and their containers but to also look around at the larger environment. Insects and rodents tend to leave droppings in areas they inhabit. Insects tend to leave behind a substance called frass, which is the undigested fibers from paper. If you see droppings and/or frass in the storage area, it is a strong sign that your materials are being exposed to pests. Small, irregular holes on paper-based enclosures are also a sign that pests have attacked your materials.

Some tips for reducing your materials' exposure to pests are to refrain from eating anywhere near your collections materials. Crumbs draw pests, so keep food far away from your collections. Another tip applying to both pests and mold is to be cautious about donated materials when you receive them. Pests and mold can hitch a ride into your facility on these materials, so having a good, clean staging area where you can inspect donated items for pest and mold evidence can help you reduce your storage environments' exposure to both.

B&W or Color Film

This question may involve unspooling the film to answer. Unspooling film is not without risk. If you are unable or unwilling to unspool your film and you have no supporting information that may answer this question, we recommend you click on "Unsure."

- B&W film is at lower preservation priority

- Color film is at higher preservation priority

- B&W negative film often has a greyish or purplish cast

- Color negative film often has an orange cast

- The easiest way to determine if a film is in color is to unspool it and look at a few frames

- If you have a film that has some parts in color and some in black and white, be sure to click on "color/both"

B&W motion picture film contains silver salt particles that are suspended in a gelatin binder. During processing, these salts are converted to metallic silver particles, which is what the image on the film is composed of.

Film Elements

This question may involve unspooling the film to answer. Unspooling film is not without risk. If you are unable or unwilling to unspool your film and you have no supporting information that may answer this question, we recommend you click on "Unsure."

Film Types Overview:

- Reversal and negative films are the highest preservation priority because they are usually irreplaceable

- Negative film often has a purplish, greyish, or orangish cast

- In negative films, the light parts and dark parts of the image are reversed (e.g. the sky will appear dark)

- Print films are the lowest in terms of preservation priority

- In print films, the images will look intuitively appropriate—light parts and dark parts are appropriate to reality (e.g. the sky is light)

- Magnetic stock is at a moderate preservation priority

- Magnetic stock has a magnetic information layer that looks like audiotape and has an dark brown to orange cast

- Magnetic stock, if it is older, often has an orangish powder on it (see below for images)

For the purposes of PSAP assessment, film has one of four elements: print, reversal, negative, or mag stock. These terms refer to how the film has been created and processed.

Print (Positive)

- Positive image

- Produced from a film negative, and projected for viewing

- Film edge is clear

A print, or positive, is created from a negative and is projected for viewing. The film holds a positive image (i.e. one that appears natural to the eye).

Negative

- Negative image; images are reversed from a positive print

- Bright places on a print are dark on a negative

A negative is a film that has light-sensitive emulsion which is exposed in the camera. The emulsion on a film negative is softer than that of a film print, so negatives should be handled with the utmost care, if they must be handled at all. Negatives should be considered a higher preservation risk because they usually represent the original generation of a film and often cannot be replaced. Film negatives are fairly easy to identify since the images on them are reversed from a positive print—bright places on a print are dark on a negative and vice versa. The film negative's image looks like a still photographic negative. For example, the sky in a negative will appear dark, whereas in a positive print or a piece of reversal film the sky will appear very light. The negative is an important element because it is used to make projection prints.

Reversal

- Positive image

- No film negative is produced; the film that is run through the camera to capture the image is the same film that is projected for viewing

- Film edge is typically black

Reversal film is similar to photographic slide film in that reversal film is run through the camera to capture the motion picture subject. After processing, the same film is projected back for viewing—there is no film negative. You can identify a projected print and a reversal film by looking at the edge of the film. If the edge near the film is clear, it is a print produced from a negative. If the edge is black, it is most likely a reversal film.

Mag Stock

- No image; holds only sound information

- Dull, brown magnetic coated film

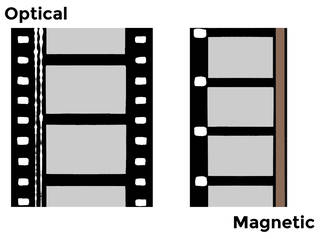

Magnetic, or "mag," stock holds sound information. It can be an entire reel on its own, or it can be a soundtrack stripe along the edge of the film. It is identified by its dull, brown magnetic recording layer. Mag stock has the same properties of magnetic audio tape and is subject to the same kind of decay—decay often related to being stored in humid conditions. It can become sticky and adhere to the film as the film is unwound from the reel.

Magnetic (Mag) Stock Breakdown

Acetate films with magnetic soundtracks are especially prone to vinegar syndrome. You can assess the breakdown by looking at the mag stripe. Is it flaking? Is it sticking to the round of the film reel? Does the film smell like vinegar?

Soundtracks

This question may involve unspooling the film to answer, but unspooling film is not without risk. If you are unable or unwilling to unspool your film and you have no supporting information that may answer this question, we recommend you click on "Unsure."

A soundtrack on film is often identified by a continuous stripe running along the length of the film. It looks considerably different than the film picture frames. The strip may be a reddish-brown color (a magnetic soundtrack). It may look like two strips that contain similar wavy forms (a variable area optical soundtrack), or it may look like a gray strip of varying darkness (a variable density optical soundtrack).

The soundtrack may not be on the film but may be a separate, individual element. For example, some film makers create a full-coat mag soundtrack, in which the magnetic oxide recording layer covers one full side of the film surface.

If your film does not have a soundtrack and it is a 35mm or 16mm, you may want to seek out production notes to determine if there are any additional sound elements. As advised in the Film Preservation Guide, preservationists should watch for commentary, dialog, or music recorded on a separate audiotape reel or cassette intended to be played with the film during screening. Amateur and avant-garde films in particular deserve special attention in this area.

Film Decay: Nitrate and Acetate

Nitrate

Nitrate in the beginning stages of decay will have a noxious odor, like "dirty socks." Be careful when testing film for odor—open the film can away from your nose and face so you are not exposed to irritating or toxic fumes and particles. You should be able to detect an odor without having your nose in close contact with the film.

The following is a guide to rating nitrate breakdown:

Deterioration Starting. As a guide to assigning a value, nitrate in this condition would have no decay or be in the earliest stages of decay. Due to the age and inherent vice of nitrate film, almost all of it will suffer from some decay. If the film is flexible, with little to no damage to the emulsion or image, it should still be considered as being in the early stages of deterioration. If you have nitrate film, PSAP recommends that you do not select "No deterioration," no matter how good the condition of the film appears to be.

Actively Deteriorating. Nitrate in this condition will exhibit emulsion damage and will most likely include image-area damage. It will have a noticeable noxious odor and may stick to itself as it is unwound. Nitrate film requires special care in handling, and a film with the "Actively Deteriorating" designation will imply some damage. As such, this film will need to be sent to a vendor for content retrieval and transfer.

If you discover you have degrading nitrate film, store it in a cold to freezing environment as soon as possible to prevent the risk of fire and to avoid further damage to the film and surrounding materials. If you do not have the resources to properly and safely handle nitrate film, contact an institution that may and strongly consider transferring the film to that institution. DO NOT throw away nitrate film! Not only could it be a valuable and unique resource, but nitrate is considered a hazardous material and must be disposed of properly.

Critical Deterioration. Nitrate film in this condition is extremely dangerous and volatile. The content of the film is most likely irretrievable as the film has congealed into a solid mass or has disintegrated into a brownish powder. Do not dispose of the film by throwing it in the garbage! You will want to contact a local HAZMAT disposal center to safely remove and dispose of this material. If you are unsure how to do so, try contacting your regional waste disposal office for further advice.

Acetate

One of the key signs that an acetate film is degrading is the presence of a vinegar smell. This degradation results from the chemical breakdown of the acetate into acetic acid and is known as "vinegar syndrome." When the film can is opened, the odor can be very strong and unmistakable.

Although the vinegar odor is often the most obvious sign that an acetate film is degrading, it is not the only sign. Acetate film that is degrading becomes brittle. The film loses its suppleness and does not gently curve around the core or reel; instead, the film appears jagged or "spoked." The film base will also shrink. Projecting a film that has shrunk will further damage the film because the sprocket holes of the film will no longer properly align with the sprockets on the projector.

To help prevent or slow acetate decay, you can place molecular sieves in your film cans. These desiccants will help absorb acetic acid and moisture in a sealed film can. You can also test the level of acetate decay by using A-D Strips. These strips, developed by the Image Permanence Institute, change color based upon the level of acidic vapor detected. A-D Strips are an excellent way to score and monitor vinegar syndrome; they can give you a finer level of assessment beyond visual and olfactory cues. The PSAP has adapted the Image Permanence Institute's A-D Strip scoring method to rate vinegar syndrome in acetate film. Using A-D Strips in conjunction with the PSAP can make your vinegar syndrome assessment much more accurate. For more information about A-D Strips, see https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/imaging/ad-strips.

The following is a guide to rating acetate decay (vinegar syndrome):

No Deterioration. This film is suffering from no acetate decay.

Deterioration Starting. Acetate decay is starting. This film should be moved to cold storage if possible and monitored. The film is flexible, with little (less than 1%) to no apparent shrinkage. There may be a very faint vinegar smell.

Actively Deteriorating. This film is actively deteriorating. It should be moved to cold storage if possible and duplicated. The film will have a stronger vinegar odor and may exhibit shrinkage (between .8 to 2%). The film may be able to be accessed and played back in-house by an experienced technician using maintained and functioning equipment. The film will also exhibit some waviness along the edges; it may curl slightly and resist lying flat.

Critical Deterioration. This film is exhibiting shrinkage and warping. It may be difficult or impossible to handle the film without damaging it. The film should be frozen if possible. The vinegar odor is unmistakable. (You should exercise caution when opening all film cans and avoid sticking your nose into the can—you could be in for a very unpleasant and potentially dangerous surprise!) The emulsion layer looks cracked and may already have separated from the film base. The film is very brittle and inflexible. It may appear to be "spoking" in the film can: the film pack does not look rounded but appears more angled. White powder may be visible on the edges of the film. In this stage of decay, the content may be unrecoverable. Acetate-based film in critical condition often cannot safely be played back in-house, if it can be played back at all. However, a highly qualified vendor may be able to recover the content, depending upon the flexibility of the film, the condition of the emulsion and image area, and the progress of shrinkage.

In order to slow or stop acetate decay, it should be stored in cold to frozen conditions (32–40°F and less than 32°F, respectively). Once the decay starts, it cannot be reversed. If a film is discovered to be acidic and succumbing to vinegar syndrome, it should be separated from other "healthy" films as it can "infect" the other films.

Film Shrinkage

Shrinkage is when the film has contracted from its original dimensions. That is, the film has become smaller through a chemical process, decay, and/or overly dry conditions. This can be a problem when the sprocket holes do not align correctly with the sprockets within the projector. If misalignment occurs, the film can be damaged. Most significant shrinkage in acetate film is due to vinegar syndrome, which also causes the film base to become brittle.

You can measure shrinkage by using a shrinkage gauge, which is a piece of equipment that measures the difference between standard sprocket holes and the film being measured.

A low-cost approach to determining if a film has shrinkage is to compare it to 100 frames of new leader. If the film is shorter than the 100 frames, it has shrunk. If the shrinkage is very obvious and dramatic (anything over half a frame difference), do not project the film!

Shrunken film can be duplicated by an experienced lab. If you have shrunken film but do not currently have the funds available to copy it, you can freeze the film to slow or halt the decay until a later time when the film can be duplicated.

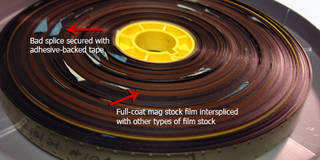

Splices

This question may involve unspooling the film to answer. Unspooling film is not without risk. If you are unable or unwilling to unspool your film and you have no supporting information that may answer this question, we recommend you click on "Unsure."

A splice is where two pieces of film are joined. Splices are usually made during film editing, although they can be made to repair a film, join two different film reels, or to attach leader to a film. You can identify splices by observing a slight overlap of film (in the case of cement splices) or tape on the film surface (in the case of tape splices).

You can check the quality of the splice by gently rotating the splice in opposite directions to see if the splice holds. If the splice is weak, dirty or has tape residue, the film around the splice should be cleaned and the splice should be removed and replaced. As directed by the Film Preservation Guide, old splicing material can be loosened by gently applying film cleaner with a lint-free cloth or cotton swab. A razor blade or other sharp tool can be helpful in removing tape. It is essential to remove all visible residue before continuing.

To repair splices, you'll need a splicer and splicing tape or cement depending upon the kind of splicer you have. Cement results in a more permanent splice, but cannot be used on polyester film. If you are splicing film with a soundtrack, be mindful that you will lose that portion of sound where you are making the splice. Additionally, the soundtrack does not align with the corresponding image, but precedes the image in projection.