Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Parchment

- Description

-

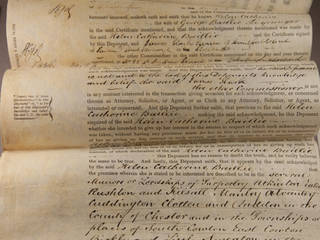

Parchment is made of animal skin (calf, sheep, or goat). The term "vellum" refers specifically to calfskin, which is often used as a binding material. Parchment was used as a writing surface from the 2nd century B.C. through the 19th century, first in the form of rolled manuscripts and later as multiple sheets bound together. While paper began to supplant parchment as early as the 15th century, parchment remained the preferred support for important legal documents and diplomas into the early 20th century.

During fabrication, parchment was treated with enzymes or lime to remove hair and flesh, scraped, and dried under tension. Depending on its intended use, the surface was often further prepared with the application of powdered pumice, vegetable oils, polishing, or a mineral ground like gesso or bole. Chalk was sometimes applied as a whitening agent.

Parchment may be identified by a number of characteristics that differentiate it from fiber-based paper. Follicle patterns, scars, veining, and fat deposits are visible under 30x magnification. Viewing through light may help to make these traits visible to the naked eye.

- Deterioration

-

Parchment is hygroscopic, meaning that it absorbs, retains, and releases moisture as it seeks balance with its environment. As a result, parchment is very sensitive to high humidity and can cockle, wrinkle, curl, and distort in moisture-heavy environments. If exposed to excessive amounts of water, such as in a flood, parchment will become gelatinized. Exposure to heat in addition to high humidity will cause parchment to shrink. Low humidity will cause parchment to dessicate and embrittle, which is particularly a concern if such objects are handled with any frequency.

Some degree of cockling and undulation is normal and not necessarily a sign of deterioration. Color and texture variation across a parchment leaf is also natural for any animal hide. Parchment should not be forced to lie absolutely flat, as the nature of the animal hide will not allow it to do so without causing stress and possible damage. Rolled, folded, or crumpled parchment should not be forced if it is rigid and does not open easily. Attempts to open or flatten such objects without the assistance of a trained conservator may result in tears and delamination.

Parchment is highly susceptible to mold. A regulated, clean storage environment should prevent mold growth. Fluctuating environment, poor storage, mold or insects may all result in damage. Inks and pigments may crack and flake off as a result of expanding and contracting caused by fluctuating temperatures and RH. As on paper, iron gall inks may fade and burn through their support.

Despite sensitivity to environmental conditions, overall parchment is quite stable. Many parchment documents that are hundreds of years old remain in good condition. Some processing techniques used in the 19th century produced a less stable product; however, some may be stiff, weak, and/or gray in color as a result of gypsum forming in the parchment (a chemical reaction between sulphuric acid and calcium carbonate). Parchment in good condition ranges in color from pale gray to strong white; a dark gray or dirty appearance may indicate the presence of gypsum.

- Risk Level

- The risk level of a parchment object varies widely based on the methods used to produce it and the storage environment in which it has been kept. Keeping an eye on relative humidity is the most important factor in parchment preservation. Parchment documents that have been stored in a consistently regulated environment will generally remain in stable condition.

- Storage

- Slight undulations and expansion/contraction of the parchment surface are normal and should be accommodated in the storage of parchment. Bound parchment items should be stored in individual boxes. Single parchment leafs should be stored in individual acid-free envelopes. If an item is unable to lie flat and would have to be forced into an envelope, it should instead be placed in a shallow box.

- Storage Environment Recommendation

- (±5°F; ±5% RH)

-

Woods in M. Kite and R. Thomson (2006)Temp/RH (Acceptable) < 65°F (18°C); 45–60% RH - Display Recommendations

- Parchment should not be adhered to a rigid mount due to its tendency to expand and contract. Parchment objects require significant preparation for exhibition, including the construction of special custom mounts to gently support the item(s). Parchment must also be protected from UV light and temperature fluctuations.

Resources

- Kite, M. & Thomson, R. (2006). Conservation of leather and related materials. Oxford, England: Elsevier.

- Pickwoad, N. (1992). Alternative methods of mounting parchment for framing and exhibition. The Paper Conservator, 16, 78-85.