Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Photographic Prints

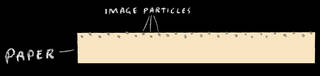

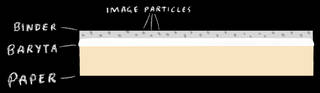

A photographic image is formed through the exposure of a photosensitive emulsion to light: this is the essence of a photograph. Photo emulsion, which is carried on a paper or plastic support, is composed of a light-sensitive image material (e.g. silver particles) dispersed in a binder substance (e.g. gelatin). Most prints are typically positive images. Photo prints may be full-color or monochrome, which means that the image is rendered using a single color (e.g. B&W prints). Monochrome prints are split into three categories: 1-layer (image material only), 2-layer (image material in a binder), or 3-layer (image material in a binder atop a baryta coating).

Monochrome Prints

1-Layer Prints (uncoated paper)

- Salt Print (1839 - 1860s)

- Cyanotype (Photo)(c. 1872 - present; technical uses, c. 1872 - 1950s)

- Platinum/Palladium Print (1873 - 1930s)

2-Layer Prints (uncoated paper w/ binder layer)

3-Layer Prints (baryta-coated w/ binder layer)

- Glossy Collodion POP Print (c. 1867 - 1930s)

- Silver Gelatin DOP Print (c. 1874 – present)

- Gelatin POP Print (1885 – 1910)

- Matte Collodion POP Print (1893 - 1920s)

Color Prints

- Color Carbro Print (early 1900s – c. 1950)

- Dye-Transfer Print (1935 - 1994)

- Chromogenic Color Print (1942 – present)

- Silver Dye-Bleach Print (1963 – c. 2011)

Instant Photos

- Instant Photo, B&W (1947 – 2008; limited production persists today)

- Instant Photo, Color (1963 – 2008; limited production persists today)

Related Notes

Salt Print

- Synonyms

-

- Salted paper print

- Dates

- 1839 – 1860s

- Surface Sheen

- Matte

- Paper Fibers

- Clearly visible

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (reddish brown (untoned), purplish brown (toned)); may appear yellowish brown or greenish yellow if faded.

- Description

- A salt print is a single-layer print comprised of an uncoated paper support with a silver image deposited in the paper fibers. A positive print is created by placing a negative in contact with the sensitized silver printing-out paper and exposing it to sunlight. Paper fibers will be clearly visible. Many silver salt print images appear to be embedded into the paper surface. The surface sheen will likely be matte and will not exhibit surface gloss; its texture will be rough due to the absence of a binder layer. If unmounted, the paper will be semi-translucent when viewed over a light source. In some cases, it may bear a watermark. The image will likely range from light brown to reddish brown (untoned) to purplish brown (toned). If the print is faded, the image may appear yellowish brown. Salt prints are typically found mounted in albums or loose.

-

Salt print matte surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas - Composition

-

Support Image Paper (uncoated) Silver - Deterioration

- Salted paper prints are sensitive to pollutants, humidity, and light. Images are often faded and may show pale yellow at their edges. Highlight details will fade first, but overall fading is also common. Untoned images will be especially vulnerable to fading. Embrittled supports, "foxing," and other types of paper staining are also common. If a salt print was retouched, it will now likely appear as a dark spot that may be mistaken as a form of deterioration.

- Risk Level

- High. A tendency toward image fading and discoloration will be greatly accelerated by environmental factors like airborne pollutants, high humidity, and light exposure. A salt print is of higher priority if it is untoned.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; image dimensions correspond to the process negative

- Background

- Although he had been working on stabilizing the format since around 1834, William Henry Fox Talbot first published his work on salted paper photography in 1839. Salted paper prints were the earliest positive print format and, until the 1850s, the primary positive process for contact-printing directly from paper negatives and glass negatives. Exposure times ranged from a few minutes to a few hours, requiring that the image be visually inspected throughout the process to determine when the exposure was complete. Before fixing and washing, the image could be toned with gold chloride to increase permanence and create a richer tone. The comparatively less arduous silver albumen print overtook the silver salt process in the mid-1850s, just before the salt print faded into obscurity in the 1860s.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. This is particularly important for salt prints, which are very sensitive to light. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Cyanotype (Photo)

- Synonyms

-

- Blueprint

- Ferro-prussiate print

- Dates

- c. 1872 - present; technical uses, c. 1872 - 1950s

- Surface Sheen

- Matte

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (brilliant Prussian blue)

- Description

- A cyanotype is a single-layer print comprised of a blue pigment image embedded in an uncoated paper’s fibers. The image color is a brilliant Prussian blue with continuous tone. Image is typically of poor contrast and sharpness. The paper fibers are clearly visible, and paper texture will likely be rough. Surface finish is extremely matte with no surface gloss due to the absence of a binder layer. Typically found in albums or loose, the process was used to produce snapshots or blueprints.

- Composition

-

Support Image Paper (uncoated) Blue pigment - Deterioration

- Cyanotypes are sensitive to light. They will fade quickly in direct, intense light but can be kept quite stable otherwise if kept in dark storage. Furthermore, faded cyanotypes can regain substantial image density when kept in dark storage. As with other early photographic processes, the paper support will often be the weakest link. Paper staining, discoloration, and embrittlement are common deteriorative traits.

- Risk Level

- Moderately low. Cyanotypes are relatively stable and image permanent if kept in dark storage conditions and out of an alkaline pH environment. The integrity of the support paper is often the decisive factor in the long term preservation of cyanotypes.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; image dimensions correspond to the process negative

- Background

- Cyanotypes were commercially produced in large numbers from the 1870s to the 1930s, but they are still made today. The cyanotype process was invented in the eighteenth century but did not attract much further development until John Frederick William Herschel's paper on the format in 1842. However, the process was still not widely adopted until the 1870s. The first commercial cyanotype paper was developed in France in 1872; the first commercial cyanotype producting machine was introduced to the United States in 1875. Pre-sensitized papers became available in 1876 from the Marion Company of Paris and were sold worldwide, including in the United States. The term "blueprint" generally refers to line drawings reproduced by the cyanotype process for schematic or technical drawings. Due to its affordability and simple processing, technical blueprints/cyanotypes were typically produced in-house by amateur photographers for the purpose of reproducing engineering and architectural designs. During the 1930s, blueprinting began to lose its popularity due to the development of the diazo process, which used vapor to develop the image rather than immersion in a liquid bath. The popularity of cyanotypes for non-technical uses underwent a revival in the 1960s. The cyanotype process has also been used to create photograms.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Cyanotypes should be stored in pH-neutral, unbuffered, paper products in order to prevent fading of the blue pigment. Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. This is particularly important for cyanotypes, which are very sensitive to light. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Platinum/Palladium Print

- Synonyms

-

- Platinotype

- Palladiotype

- Dates

- 1873 – late 1930s

- Surface Sheen

- Matte

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (neutral gray-black, warm brown, brown-black, or purple/blue-black)

- Description

- A platinum/palladium print is a single-layer print comprised of a platinum or palladium image embedded in uncoated paper’s fibers. The surface is extremely matte with no surface gloss due to the absence of a binder layer. The paper fibers are visible, and the image exhibits no fading or silvering. Images can be characterized as rich and soft with a mid-tone density value ranging from silver-gray to black, although warmer tones were achievable through the use of additives/toning. This resulted in color tones ranging from warm brown to sepia, brown-black, and, in some cases, purple/blue-black. Cyanotypes are typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose.

-

Platinum print matte surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas - Composition

-

* Gold, uranium, and iron additives fairly commonSupport Image Paper (uncoated) Platinum or Palladium* - Deterioration

- Platinum and palladium are the most long-lasting of all chemical photo processes. The metal image itself is permanent and will exhibit no fading. The paper support, however, will face a heightened risk of yellowing and embrittlement due to the image’s inherent acidity. The support will have little flexibility—avoid handling prints for this reason. Deterioration of the paper support will often shift the image toward a warmer tone in the highlights. If the image surface has been stored in contact with another piece of paper, there may be signs of catalytic degradation in the form of a mirror image "burned" into the facing paper. This staining is irreversible—do not house platinum prints in direct contact with other photographic materials!

- Risk Level

- Low. The integrity of the support paper is the decisive factor in long term preservation. Platinum and palladium images are among the most permanent photographic image materials yet pose an enormous threat due to their paper support. Do not allow unnecessary handling and consider creating access copies.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; Image dimensions correspond to the process negative

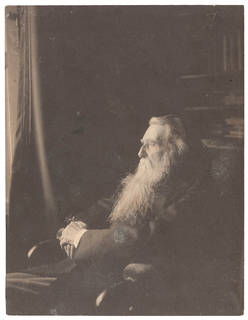

- Background

- Platinum prints were produced from 1873 to the late 1930s. They were expensive to produce and therefore were typically used for high-end portraiture and fine art photography. Inflation of platinum prices near the turn of the century gave rise to the palladium print, or palladiotype, which simply substitutes metal palladium for platinum. Palladium prints lack the tonal range of platinum prints but are otherwise analogous, chemically and visually.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Due to the platinum print’s inherent acidity, storage in a buffered, alkaline enclosure is recommended. Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Include a rigid secondary support within this enclosure. Position image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure and not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large prints. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

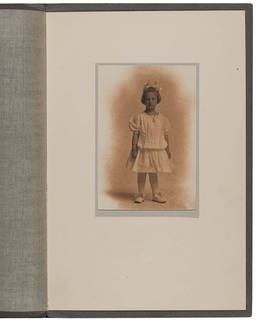

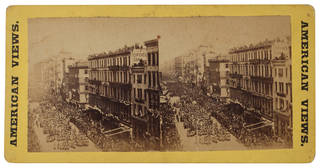

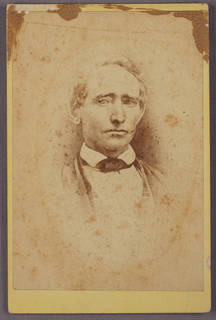

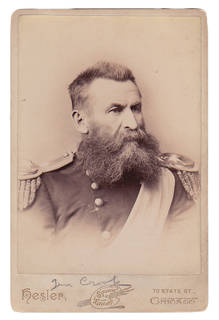

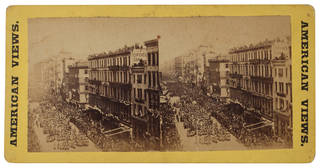

Albumen Print

- Dates

- 1850 – c. 1895

- Surface Sheen

- Semi-glossy to glossy

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (purplish brown to chocolate brown)

- Description

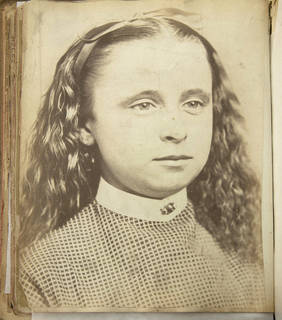

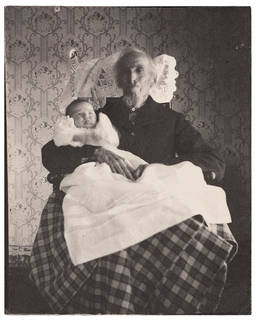

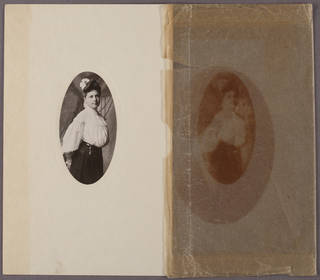

- An albumen print is a two-layer print comprised of a paper support with an albumen binder and silver image. Prints were generally produced on smooth-surfaced thin paper. Depending on the period, burnishing and rolling techniques may or may not have been implemented to smooth the surface after mounting. The surface sheen therefore may range from semi-glossy (1850 – c. 1870) to glossy (c. 1870 – c. 1895). Paper fibers are clearly visible. The monochromatic image tone is commonly purplish brown but may vary from warm chocolate brown to yellowish brown (when faded). Prints after 1855 were always toned with gold chloride. Papers after 1860 may have been tinted with a pink or blue dye in order to mask the natural yellowing of the albumen layer. Albumen prints are typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose. The print’s thin paper support is usually found on a cardstock mount as a carte-de-visite (2½" × 4¼"), cabinet card (6¼" × 4"), or stereocard (about 3½" × 7").

- Composition

-

* Gold toning commonSupport Binder Image Paper Albumen Silver* - Deterioration

- Albumen prints will likely exhibit yellowing and some fading. Most albumen prints exhibit distinct yellow or yellowish brown staining in the non-image and highlight areas. As the albumen binder tends to yellow, overall print discoloration follows. Highlights tend to lose image contrast and detail first. A cracked or crazed pattern may be seen in dark areas, particularly in the case of a thin emulsion coating or an unburnished print. If the print is unmounted from its cardstock mount, it will curl up very tightly. Some albumen prints will suffer a form of paper staining known as foxing. Foxing is characterized by the appearance of reddish brown blotches and will often occur in patches. If an albumen print was retouched, it will now likely appear as a dark spot that may be mistaken as a form of deterioration.

- Risk Level

- Moderately high. Albumen prints are sensitive to light, pollutants, and humidity. High humidity and excessive light exposure will accelerate fading and the deterioration of the albumen binder. High humidity may also cause foxing to occur. Low humidity will cause albumen to crack and delaminate. Folds, creases, and general mishandling will also cause cracking and fissuring.

- Common Size(s)

- Typically mounted on cards. 2½" × 4" –4¼" (carte-de-visite); 4¼" × 6½" (cabinet card); 3–4½" × 7" (stereocard)

- Background

- The albumen process for photographic prints was first presented and published by Louis Blanquart-Evrard in 1850. Albumen prints were produced from 1850 to around 1895. Albumen prints were the dominant print medium for commercial photography between 1860 and the 1890s, replacing daguerreotypes as the prevailing portrait medium. Albumen carte-de-visite portraits were incredibly popular, allowing people to collect photographs of their family members and prominent public figures alike. After 1885, albumen was gradually superseded by gelatin and collodion-based prints.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Carbon Print

- Analogous

-

- Monochrome carbro print

- Dates

- 1855 – 1950s

- Surface Sheen

- Differential; dark areas of image appear glossy while highlights appear semi-matte

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (neutral black, reddish brown, or chocolate brown)

- Description

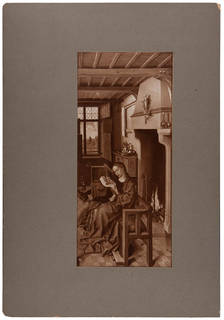

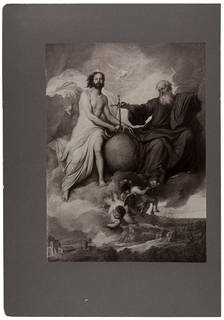

-

A carbon print is a two-layer print comprised of a paper support with a carbon black pigment image carried by gelatin. The surface exhibits differential sheen, with dark areas of the image appearing more glossy than semi-matte highlights. Thicker application of the pigment on the gelatin is relative to the density of the image and will lend toward a subtle relief effect. Although any pigment color is possible, carbon images are recognizable by their dense, dark tones, which are generally either neutral black, reddish brown, or chocolate brown. Carbon prints may be printed on a variety of colored papers, whose fibers will be visible in highlights.

Although created through different processes, a carbon print and a monochrome carbro print will appear indistinguishable: each possesses the same key elements and a similar image stability. A carbon print may be labeled "Permanent" or "Autotype." They are typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose. Carbon prints may also be quite large in size.

-

Carbon print differential surface gloss visible in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas - Composition

-

Support Binder Image Paper Gelatin Carbon black pigment - Deterioration

- Carbon images will exhibit little to no fading or yellowing. Carbon black is among the most light stable of pigments. Darker areas of the image may develop large cracks, where the gelatin layer is thickest. As with all prints on paper, they are susceptible to mechanical damage and staining. When found unmounted, carbon prints will have a tendency to curl in on themselves.

- Risk Level

- Low. As carbon prints contain pigment rather than silver or other unstable components, the integrity of the support paper is the decisive factor in the object’s permanence, as is their display and storage history.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; Image dimensions correspond to the process negative

- Background

- Carbon prints were produced from 1855 to the 1950s, and they were popular between 1870 and 1910. Because of their rich image quality, carbon prints were often used for portraiture, fine art, and fine art reproduction. Although understood as a stable and rich alternative to silver processes, carbon prints never reached a wide audience, largely due to the time and effort their production demanded.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

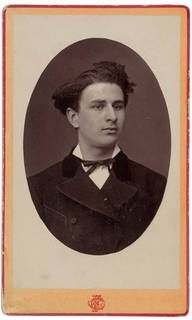

Glossy Collodion POP Print

- Synonyms

-

- Collodion POP print

- Collodion printing-out paper

- Collodion-chloride

- Dates

- c. 1867 – 1930s

- Surface Sheen

- Semi-glossy to glossy; may exhibit iridescent effect when viewed under fluorescent lights.

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (purple-brown if toned; reddish-brown if untoned or faded)

- Description

- A glossy collodion print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support with a baryta layer, collodion binder, and a silver image. The surface finish ranges from semi-glossy to glossy due to the thick baryta layer. Baryta layer may be tinted, exhibiting an overall pink, blue, or green tint. A collodion print may also have a glazed surface, resulting in a high-gloss finish. Most glossy collodion prints exhibit a subtle iridescent effect on their surface when viewed under fluorescent lighting. Image tones range from reddish-brown to purple or violet brown. Paper fibers will not be visible. A collodion print may be difficult to distinguish from the gelatin POP; it is not, however, often critical to make this distinction. Typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose, collodion prints were often produced as cabinet cards.

-

Glossy collodion print surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas -

Glossy collodion print surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas - Composition

-

* Toning commonSupport Paper Coating Binder Image Paper Baryta Collodion Silver* - Deterioration

- Collodion prints exhibit very little image fading. Collodion prints are extremely sensitive to surface abrasion, resulting in white scratch marks where the image material has been removed and the baryta layer is exposed. This is a distinctive trait of collodion print deterioration. The collodion layer may also delaminate or exhibit tiny cracks due to fluctuating relative humidity and/or mishandling.

- Risk Level

- Moderate. Care must always be shown when handling collodion prints to avoid abrasion, scratching, and surface wear. Do not attempt to clean print surface. A stable environment should also prevent the emulsion from delaminating.

- Common Size(s)

- Larger sizes are rather rare. Image dimensions will often correspond to gelatin glass plate negatives of the era: 2½" × 2½"; 2½" × 4"; 4" × 5"; 5" × 7"; 8" × 10"; 11" × 14"; 14" × 17"; 16" × 20"; 18" × 22"; 20" × 24"

- Background

- Collodion prints were produced from around 1870 into the 1930s; and, they were used for portraiture, landscape, and architectural photography. Glossy collodion papers were the first emulsion type printing-out-paper (POP) to be marketed. Due to the public’s favor for glossy commercial portraiture at the time, collodion POP’s popularity rose quickly in the 1880s but fell second to the more versatile gelatin POP in the following decade. By the end of the 1930s, collodion prints had faded from use.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, since it contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Silver Gelatin DOP Print

- Synonyms

-

- Gelatin silver print

- B&W print [colloquial]

- Gelatin silver developing-out paper print

- Gelatin silver bromide print

- DOP print

- Dates

- c. 1874 – present

- Surface Sheen

- Matte, glossy, or textured

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (neutral gray-black [untoned]; brown, sepia, yellowish, or purplish [toned])

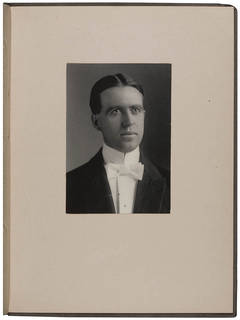

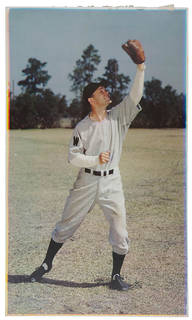

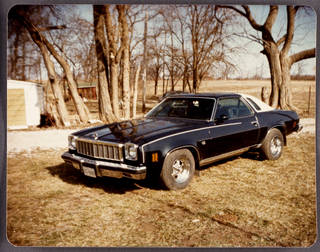

- Description

- A silver gelatin print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support with a baryta or resin coating, a gelatin binder, and a silver image. Prints are made using a light-sensitive gelatin silver bromide or gelatin silver chloride paper, and a negative. The surface sheen may be matte, glossy, or specially textured. In most cases, no paper fibers are visible, obscured behind a thick baryta layer (fiber-based paper) or a behind a pigmented polyethylene layer (resin-coated paper). Some of the earliest papers (those prior to 1900) may have a thin baryta layer. Resin-coated prints can be identified by their smooth, plasticized back side. The untoned print image will be neutral gray-black unless severely deteriorated. Many resin-coated prints, however, were toned. They typically appear within the range of brown or sepia, but yellowish and purplish tones are also common. Silver gelatin photo postcards (c. 1900–1940s) can be identified by their continuous tone image, which they do not share in common with photomechanical postcards, and postal back printing. Silver gelatin prints are typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose.

- Composition

-

Support Paper Coating Binder Image Paper (fiber-based, FB; resin-coated, RC) Baryta (fiber-based, 1890s – present) or Polyethylene (resin-coated, after 1968) Gelatin Silver - Deterioration

- Silver gelatin images often exhibit silver mirroring due to oxidation, causing the silver particles to rise to the top of the gelatin layer. This defect is typically more acute along the edges and in darker areas of the image. Image fading is first and most apparent in highlights. Discoloration (yellow-brown) and fading in highlights, at edges, or across the image are often symptoms of air pollution or poor storage materials. Resin-coated silver gelatin prints are exclusively susceptible to redox blemishing, which appear as small orange-yellow spots in the image. Fiber-based prints will have a tendency to curl, usually as a result of fluctuating humidity.

- Risk Level

- Fiber-based: Moderately low. Resin-coated: Moderate. Exposure to air pollutants is often the significant prolonged threat to silver image materials, but warm and humid environments will only accelerate the destructive effects. Resin-coated prints’ surfaces may stick to one another under extreme heat. Resin-coated prints are also more susceptible to light damage than fiber-based.

- Common Size(s)

- 3½" × 5" ; 5" × 8" ; 8" × 10" ; 11" × 14" ; 16" × 20" ; 20" × 24" ; 24" × 30"

- Background

- Silver gelatin prints have been in common use from around 1874, when the first commercial silver gelatin paper was created, up through today, although its popularity has ebbed since the rise of digital photography. Nevertheless, black-and-white silver gelatin prints are by far the most common type of monochromatic photograph. Silver gelatin prints were the dominant black-and-white photographic process of the twentieth century, and their sizable presence in many archives and special collections reflects this. Unlike the printing-out process, which allowed exposure to be monitored while an image gradually appeared, the developing-out process required a "light-tight" room and precise exposure times. The process of developing-out prints became widely used and resulted in making new forms of industrial printing possible. Silver gelatin photographic postcards were common from about 1900 through the 1920s and featured families, local athletes, and worldwide celebrities as subject material. Resin-coated papers were introduced in 1968 and were immediately popular. By the early 1970s, resin-coated paper accounted for about 70% of the photographic paper market share.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

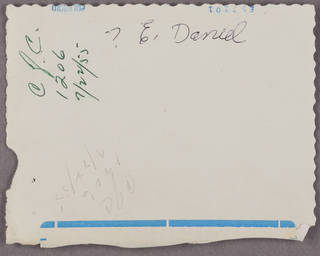

- Backprinting

- Manufacturer backprints will often help to both identify the format as well as to determine the time period. The absence of backprints should not definitively rule out a format or period. Common Kodak backprinting will include "Velox" (late 1920s – c. 1950s), "Kodak / Velox / Paper" (c. 1950 – mid 1960s), "A Kodak Paper" (1960s – early 1970s), and "THIS PAPER / MANUFACTURED / BY KODAK" (1970s – 1980s). Before the late 1950s, "Agfa" was followed by the brand name (e.g. "Agfa Lupex" ); after the late 1950s, the brand name was dropped and backprints simply read "Agfa".

Gelatin POP Print

- Synonyms

-

- Gelatin printing-out paper

- Citrate paper

- Solio [Kodak]

- Dates

- 1885 – 1910

- Surface Sheen

- Matte to glossy

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible, although texture will suggest fiber contours

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (red-brown to purple-brown or light yellow-brown to yellow-green)

- Description

- A gelatin POP print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support with a baryta layer, gelatin binder, and a silver image. Gelatin POP prints have a matte surface when air-dried or a glossy surface achieved through ferrotyping (drying the print in contact with a polished metal or glass surface) or burnishing. Baryta layer may be tinted, exhibiting an overall pink, blue, or green tint. Image colors range from reddish-brown (untoned) to purple (toned) or, when faded, from yellow-brown to yellow-green. Paper fibers are not visible. Gelatin POP prints may be difficult to distinguish from collodion prints. It is not crucial to make this distinction, as generally the only variable that sets each apart is the binder material. Gelatin POP prints are typically found framed, mounted in an album or as cabinet cards, or loose.

- Composition

-

* Gold toning commonSupport Paper Coating Binder Image Paper Baryta Gelatin Silver* - Deterioration

- Gelatin POP prints are often faded and yellowed. The gelatin binder is very sensitive to high and low humidity. Excessively low humidity will cause the gelatin to crack, while high humidity will cause gelatin to soften and stick to adjacent objects or enclosures. Gelatin POP prints are also very sensitive to abrasion; in some cases, deep scratches and abrasion will remove the image layer, exposing the stark white baryta layer. Unmounted or poorly mounted gelatin POP prints will have curling and warping issues.

- Risk Level

- Moderate. Care must always be shown when handling collodion prints to avoid abrasion, scratching, and surface wear. Do not attempt to clean print surface. A stable environment should also prevent the emulsion from delaminating.

- Common Size(s)

- Image dimensions will often correspond to gelatin glass plate negatives of the era: 2½" × 2½" ; 2½" × 4" ; 4" × 5" ; 5" × 7" ; 8" × 10" ; 11" × 14" ; 14" × 17" ; 16" × 20" ; 18" × 22" ; 20" × 24". Larger sizes are rather rare.

- Background

- The gelatin POP process was often used in commercial portraiture at the end of the 19th century. Most gelatin POPs were produced on cabinet card supports. The POP process involves contact-printing a negative onto paper using a light source. This process met consumer demand for newer small-format cameras as well as existing large-format cameras. POP allowed for exposure using gaslight, kerosene lamps, or electrical lightbulbs and for exposure to be monitored while an image gradually appeared.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Matte Collodion POP Print

- Synonyms

-

- Matte collodion POP print

- Matte collodion printing-out paper

- Dates

- 1893 – 1920s

- Surface Sheen

- Semi-matte with slight luster

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (neutral gray-black, brownish black, or purplish black)

- Description

- A matte collodion print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support with a baryta layer, collodion binder, and a silver image. Owing to a thinner baryta layer than its glossy collodion counterpart, the surface will have a semi-matte quality with only a slight luster. Matte collodion images should be assumed to be toned; they will range in color from neutral gray-black to a near neutral brownish black to purplish black. Matte collodion prints were most often toned with gold and platinum, which gave them an appearance similar to platinum prints. Their surface will not appear faded due to the common use of stabilizing toners. Matte collodion are often found in the form of cabinet cards or are mounted in a paper folder.

-

Matte collodion print surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas -

Matte collodion print surface viewed in raking light. Video courtesy of Image Permanence Institute, Graphics Atlas - Composition

-

* Gold and platinum toning commonSupport Paper Coating Binder Image Paper Baryta Collodion Silver* - Deterioration

- Due to a strong reliance on gold and/or platinum image toning, matte collodion print images are exceptionally stable. Matte collodion typically have greater stability than the glossy collodion, although, while they exhibit less fade and silver mirroring, matte collodion will slightly fade and yellow over time. As with all collodion prints, they are sensitive to surface abrasion. They may exhibit white scratch marks where the image material has been removed and the baryta layer is exposed. The collodion layer may also delaminate or exhibit tiny cracks due to fluctuating relative humidity and/or mishandling.

- Risk Level

- Moderate. Care must always be shown when handling collodion prints to avoid abrasion, scratching, and surface wear. Do not attempt to clean print surface. Stable humidity should also prevent the emulsion from delaminating.

- Common Size(s)

- Image dimensions will often correspond to gelatin glass plate negatives of the era: 2½" × 2½" ; 2½" × 4" ; 4" × 5" ; 5" × 7" ; 8" × 10" ; 11" × 14" ; 14" × 17" ; 16" × 20" ; 18" × 22" ; 20" × 24"

- Background

- Matte collodion prints were produced from 1893 into the 1920s. Both their commercial introduction in the 1890s and their divergence from the earlier collodion POP print were based on the public’s preference for platinum and matte surfaced prints. Matte collodion prints were meant to mimic the appearance of platinum prints. While both types of prints were reliant on image toning, matte collodion POP prints were cheaper to produce. Matte collodion paper was the material of choice among portrait photographers until 1910, when the more convenient silver gelatin-based print paper emerged.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

The duration of an exhibit should be determined in advance, and no item should be placed on display permanently. Most items should not be displayed for longer than 3 to 4 months, assuming other conditions such as light levels, temperature, and relative humidity are within acceptable ranges. Facsimiles or items of low artifactual value may be exhibited for longer periods of time. Between display periods, it should be returned to an appropriate environment where it may "rest" in dark storage.

Light levels should be kept as low as possible. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize this exposure. Display cases should be enclosed and sealed to protect their contents, and their items should be securely framed or matted using preservation-quality materials that have passed the Photographic Activity Test (ISO18916).

For more information on exhibition management, see Exhibition Guidelines.

Color Carbro Print

- Synonyms

-

- 3-color carbro

- Tri-color carbro

- Tri-chrome carbro

- Dates

- early 1900s – c. 1950

- Surface Sheen

- Differential gloss: glossy in dark areas, semi-matte in highlights

- Paper Fibers

- Partially visible

- Image Tone

- Full-color (cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes)

- Description

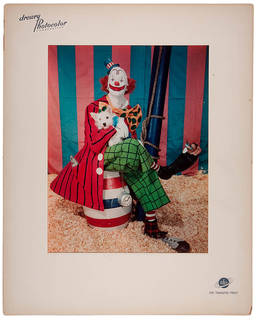

- A carbro print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support and an image with three pigmented gelatin layers. Carbro printing is a tri-color variation of the carbon pigment printing process. Each gelatin layer is printed from a B&W negative produced through a colored filter. After the layers have been processed, they are superimposed on a paper support to create a 3-color image. Print surface will exhibit a differential gloss as a result of the thicker pigmented gelatin in dense areas and thinner gelatin in light areas. Darker areas are glossy, while highlights have a semi-matte surface finish. This disparity is especially apparent between high- and low-density image areas. Color layers will often seem misaligned or separated, particularly at borders and in areas of fine detail. Another common printing flaw is the wrinkling, creasing, or frilling of gelatin-pigment layers. Pigment particles can be seen throughout the image under low magnification. Carbro prints are known for their vivid 3-color values and image permanence, and they are synonymous with color magazines and advertising imagery of the era.

- Composition

-

Support Image Paper 3 layers of pigmented gelatin: cyan, magenta, and yellow - Deterioration

- Since the pigments used to form carbro print images are particularly stable, carbro prints show little to no image fading and no yellowing. Unstable environmental conditions, especially low relative humidity, may cause the pigmented gelatin layers to delaminate or crack, especially in dark areas where the gelatin is thicker. Carbro prints are also sensitive to abrasions, scratches, and general physical damage.

- Risk Level

- Moderately low. As carbro prints contain pigment rather than silver or other unstable components, the integrity of the support paper is the decisive factor in the object’s permanence. Yet, the print's display and storage history are also significant factors in determining preservation needs. Carbro prints should not be stored in excessively dry storage conditions in order to avoid delamination or cracking of the pigmented gelatin layers.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; image dimensions correspond to the process negative

- Background

- Carbro prints were produced from the early 1900s to 1950. Carbro was the standard process for high-end advertising, particularly in fashion magazines, until the 1950s when the less expensive and more flexible dye-transfer process won over magazine publishers. The Autotype Company produced carbro materials until 1953, but they remained available into the 1960s. The Vivex color process, which was produced from 1931 until stalled by World War 2 in 1939, was a commercial printing process based on the tri-color carbro.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 32–40°F (0–4°C) RH 30–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

Dye-Transfer Print

- Synonyms

-

- Dye imbibition print

- Dates

- 1935 - 1994

- Surface Sheen

- Glossy, sometimes semi-matte

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Full-color (cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes)

- Description

- A dye-transfer print is a three-layer print comprised of a paper support with a baryta layer and an image made up of yellow, magenta, and cyan dyes held in a single gelatin layer. A dye-transfer print may be identified by misalignment of the color dye layers, mainly visible along the edges of high and low density areas. Similarly, under magnification, the image details will appear soft, and there will be no discernible color particles. The non-image margins may also have dye stains. When viewed under UV light, the magenta dye fluoresces orange. Dye-transfer prints were for some time the only color print process with a fiber-base support, and they may be identified as such. The baryta layer is very thick, which obscures all evidence of paper fibers. The surface is smooth, showing no relief or differential sheen. Dye-transfer prints will most likely be clearly identifiable as either studio or high-end production photography.

- Composition

-

Support Paper Coating Binder Image Paper Baryta Gelatin "image-receiving" layer Yellow, magenta, and cyan dyes - Deterioration

- Dye-transfer prints are sensitive to light and water; they are ideally kept in a dark, low humidity storage environment. If they are protected from prolonged exposure to light, dye-transfer prints will maintain excellent image stability and exhibit little dye fading and no discoloration. On the whole, dye-transfer will display little to no image fading. Yellow or magenta dye bleeding may be a result of water exposure.

- Risk Level

- Moderately low. They are more stable in dark storage than any other Kodak color print process. If kept in the dark except for occasional viewing or short-term display, they can last over 100 years without significant change. Dye-transfer prints should neither be stored in humid environments nor exposed to intense light for prolonged periods. Wetting the print surface may cause the dyes to bleed or run.

- Common Size(s)

- Typically medium to large format: 8" × 10" ; 11" × 14" ; 16" × 20"

- Background

- First released in 1935 as Kodak’s Wash-Off Relief Process, the dye-transfer process was improved and renamed as the Original Kodak Dye Transfer Process in 1946. Dye-transfer printing is a highly complex process that allowed unparalleled control over color levels and development. It was expensive and difficult to master, existing primarily in the domain of professional labs. Perfectly-registered prints were difficult to achieve by those who were not expert technicians. Dye-transfer was touted as the preferred color print process for artists and collectors because of both this control and the permanence of the image. Eastman Kodak ceased production of dye-transfer materials in 1994, essentially ending the widespread use of this process.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. RH 30–50% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Dye-transfer prints should be stored in nonbuffered storage materials, since the prints are stabilized at an acid pH (acetic acid bath). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- About the Process

- Although dye-transfer prints are considered photographic images, they are not the result of direct exposure to light. Rather, they are created by a series of dye layers applied using special dye-transfer matrix film. Each matrix film (one for each dye color) used to create the print has a gelatin layer, which varies in thickness according to the image density. This in turn controls how much dye is picked up by those areas of the gelatin when the matrix film is submerged in the dye solution. Each color layer is transferred to the print surface by bringing the matrix film in contact with the paper surface.

Chromogenic Color Print

- Synonyms

-

- Chromogenic process print

- Dye coupling print

- Color-coupler print

- C-print

- Popular brand names: Kodacolor, Ektacolor

- Dates

- 1942 – present

- Surface Sheen

- Varies; matte to high gloss in addition to numerous other surface textures

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Full-color (cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes); may have yellowish or reddish cast if faded

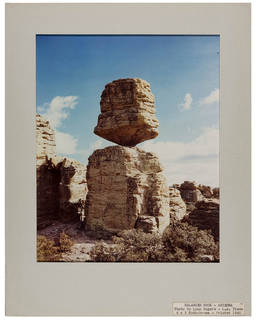

- Description

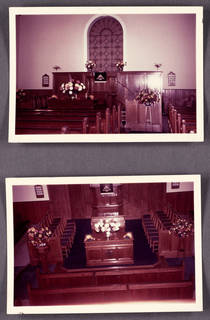

- A chromogenic color print is a three-layer "full-color" print comprised of a paper support with gelatin binder and an image made up of three dye layers: yellow, magenta, and cyan. If produced after 1968, the support is most likely resin-coated. Chromogenic prints often will be identifiable by the manufacturer’s print on the back of the support paper (backprint) or by the stamp left by the photo-processor on the print's back. Information about the process, date, and materials used are usually included in these stamps. White borders will appear on fiber-based prints but were abandoned with resin-coated prints. Chromogenic prints are by far the most common type of color photograph. They are typically found framed, mounted in albums, or loose.

- Composition

-

Support Paper Coating Binder Image Paper (fiber-based, FB; resin-coated, RC) Baryta (fiber-based, 1942–1971) or Polyethylene (resin-coated, after 1968) Gelatin 3-color dye layers of gelatin silver bromide emulsion: Yellow, magenta, cyan - Deterioration

- Chromogenic color prints are extremely sensitive to light and humidity, and they will exhibit some dye fading even if kept in dark, cold storage. Early chromogenic prints from before the 1980s are especially prone to coupler staining due to dye instability. Staining is a typical form of deterioration caused by light exposure and inherent coupler print-out; it is most apparent in highlights and borders. Yellow staining results from the fading or loss of magenta dye. Prints created before the 1980s may have reddish image discoloration as a result of the unstable cyan dye’s severe thermal fading and poor storage in high temperatures. Unlike other photographs, the progressive improvement of color print stability is linear since coupler staining and dye stability have gradually improved over time.

- Risk Level

- Moderately high. Chromogenic prints are extremely sensitive to light and humidity. They should be stored in a cool, dark environment in order to slow dye fading. Cold storage is ideal. A chromogenic print produced prior to the mid-1980s will invariably lose its image in time, even in dark storage.

- Common Size(s)

- 3½" × 5" ; 4" × 6" ; 5" × 7" ; 8" × 10" ; 11" × 14" ; 16" × 20" ; 20" × 24" ; 20" × 30" ; 24" × 30"

- Background

- In 1942, Kodak introduced Kodacolor, the first consumer "snapshot" quality positive (and negative) color print on paper process. Although popular, chromogenic prints faded and discolored quickly due to unstable dye couplers. By the mid 1960s, many of the challenges to dye stability and print quality were resolved; and, chromogenic prints overtook black-and-white across the amateur market. Fiber-based papers with baryta brightener were produced from 1942 to 1971. Resin-coated polyethylene paper with titanium dioxide brightener have been produced from 1968 up through the present day.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Ideal range 28-36°F (2°C) for 30–40% RH The colder the temperature, the longer the lifetime of the dyes.

- Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of the enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Display Recommendations

-

Light exposure should be limited. This is especially true of prints made before 1965.

- Other Chromogenic Print Supports

-

There were many forms of the color print that failed to take off, including some that will appear to be chromogenic color prints as profiled in this description. Be aware that some structural variations of the dye coupler print exist.

Polyester supports (1979 – present): These show up in a few contemporary Fuji and Ilford formats and in Kodak's Endura Display. An extremely glossy surface makes them appear similar to a silver dye-bleach print. There will also be no backprint.

Acetate supports (1941 – 1981): Kodak’s Minicolor (wallet-sized; renamed Kodachrome Print) and Kotavachrome (large-scale professional format; renamed Kodachrome Professional Print). Other than their white-pigmented acetate support, the Minicolor and Kotavachrome were structurally identical to chromogenic prints. Both formats were introduced in 1941, a year before Kodachrome, and were available until the mid-1950s. More obscure formats employing acetate supports persisted until the early 1980s.

Silver Dye-Bleach Print

- Synonyms

-

- Cibachrome print

- Ilfochrome Classic prin

- Dye destruction print

- Dates

- 1963 – 2011

- Surface Sheen

- Extremely high-gloss or semi-gloss ("pearl")

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Full-color, highly saturated colors (cyan, magenta, and yellow azo dyes)

- Description

- A silver dye-bleach print is a three-layer "full-color" print comprised of a paper support and an image made up of three gelatin layers, each containing an azo dye image: cyan, magenta, and yellow. The support can be polyester, pigmented acetate, or resin-coated. The three silver bromide gelatin emulsion layers are each sensitized to a different spectral region. After the paper is exposed using a positive color transparency, it is developed and then bleached, selectively destroying pre-formed dyes. The dye molecules remaining after the image has been developed and bleached constitute the direct positive image from the positive transparency used during the exposure. The silver dye image has vivid colors, high contrast, and minimal fading. The surface may be either a semi-gloss ("pearl") or high-gloss finish. Resin-coated paper will have a manufacturer’s backprint, while plastic-based supports likely will not. In some cases, there may also be a black margin around the image.

- Composition

-

Support Paper Coating Image Polyester, Acetate, or Resin-Coated Paper Resin (only if on paper) Silver; Gelatin w/ yellow azo dye, gelatin w/ magenta azo dye, gelatin w/ cyan azo dye - Deterioration

- Silver dye-bleach prints are highly sensitive to water, pollutants, abrasion, and fingerprints. Wetting may cause distortion, delamination, and dye migration. Image quality is high and will exhibit little to no image fading because silver dye-bleach prints are produced using azo dyes, which are relatively light stable. Polyester supports have strength and provide excellent image stability. Resin-coated supports curl and will embrittle and crack due to light exposure and fluctuating relative humidity. Acetate supports will yellow and eventually exhibit vinegar syndrome. Long term display should be avoided as prolonged light exposure and airborne pollutants will cause color to shift.

- Risk Level

- Moderately low. Silver dye-bleach prints have superior stability in dark storage. They are considered to be essentially permanent when kept in the dark. This, of course, supposes that the print is on a polyester support instead of on the rarer acetate or resin-coated paper support. Polyester supports are low risk and quite stable. If on resin-coated paper or acetate however, support instability will be the weakest link in terms of photographic permanence. Care should be taken when handling prints to avoid placing fingerprints on or abrading the glossy surface. Very humid or wet environments may cause considerable deformation and delamination.

- Common Size(s)

- Varied; medium and large format prints (due to enlargement) are common

- Background

- Silver dye-bleach prints were produced from 1963 to 2011. The Cibachrome process was based on a color motion film process called Gasparcolor, which was developed by Bela Gaspar in 1933. Ciba-Geigy introduced the modern version of this process in 1963 when polyester and resin-coated papers were released under the names Cilchrome and Cibachrome. Pigmented acetate supports were also manufactured but only lasted into the late 1970s. Ciba acquired Ilford in 1967 and championed the Cibachrome process throughout the next two decades before selling it to International Paper Corp in 1989. The product was then renamed Ilfochrome in 1991. Ilford ceased production of Ilfochrome products and processing chemicals in 2011. Silver dye-bleach prints are noted for their high image quality and permanence, making them a popular choice for those creating fine art prints.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Temp. < 68°F (20°C) RH 30–50% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Acid-free (pH 7.2–9.5) enclosures and/or folders strongly advised (ANSI IT9.2). Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from handling damage (fingerprints, creases), dust, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival-quality, acid-free) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Position photo image material away from seams in paper enclosures. Seams should be on the sides of a paper enclosure, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

Instant Photo, B&W

- Synonyms

-

- Internal dye diffusion transfer print

- Diffusion transfer

- Polaroid

- Dates

- 1947 – 2008; limited production persists today

- Surface Sheen

- Glossy

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Monochrome (neutral gray-black)

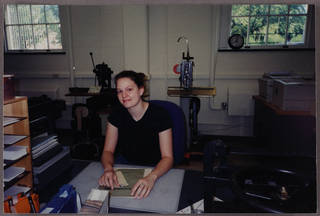

- Description

- A black-and-white instant photo is comprised of a paper or plastic (rare) support, gelatin binder, and silver image. The image is produced by an alkaline induced dye diffusion transfer process. B&W instant photos are generally of the peel-apart variety. B&W integral photos do exist (Polaroid type 600) but are rare. All the chemicals necessary to create the print are self-contained within or facing the support material. They are activated when the exposure is made and the image is squeezed through rollers ejecting it from the camera. The surface sheen will be glossy. The most common format dimensions are 3 ¼" × 4 ¼" and 2 ½" × 3 ¼" (Polaroid roll film with perforated edges). Polaroid prints after 1968 will feature a manufacturer's stamp identifying the film type and manufacturing date in alphanumeric code. Polaroid did not produce a B&W film other than those that required the protective polymer coater until 1970.

- Composition

-

Support Paper Coating Binder Image Paper (peel-apart) Baryta (peel-apart) Gelatin Silver - Deterioration

- Sensitivity to abrasion and environmental pollutants depends on how the print was produced. Generally, B&W instant photos commonly fade around the edges and develop discolored patches throughout the print. Properly coated peel-apart prints are resistant to abrasion, but more susceptible to chemical contaminants. B&W photos manufactured by Polaroid before 1970 required the print to be hand-coated with a protective polymer. If applied unevenly, uncoated areas may develop yellowing, loss of detail, and increased sensitivity to abrasion. The white border found around instant photos should never be cut off or removed; it provides a barrier to atmospheric pollutants and removal would also weaken the structural integrity of the photograph. Unmounted prints may curl.

- Risk Level

- Moderate. The absolute uniqueness of the item/image should factor in an instant print’s value appraisal and preservation. Preservation risk largely depends on whether the image was produced according to the film specifications (e.g. whether processing chemicals have been neutralized, whether a protective coating was correctly applied), and the type of film (peel-apart, coated peel-apart, or integral). On the whole, B&W instant photos are more stable than color instant photos, but as with all silver-based photographs, they are susceptible to light fading and oxidative deterioration.

- Common Size(s)

- 3¼" × 4¼" ; 2½" × 3¼" ; 2⅛" × 2⅞" ; 2⅞" × 3¾" ; 4" × 5"

- Background

- B&W instant photos were produced from 1947 through the late 2000s. The instant photographic process was developed by Edwin Land, one of the cofounders of the Polaroid Corporation, who sought to create a photographic process that did not require a darkroom. He believed there would be a large market for photographs that could be exposed and developed immediately. Polaroid was the first to manufacture instant photographic film and cameras, with the release of the Land Camera in 1947. Instant photos were popular among a wide range of consumers and used for many applications, from spontaneous family snapshots, to test shots made by professional photographers, to original fine art prints created by artists. After the end of Polaroid’s instant film production in 2008, The Impossible Project began the manufacture of instant photo products in 2010, but in limited, boutique numbers.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is better unless frequently used (frequent and sudden changes in temperature and relative humidity could result in physical stress to the object). Allowable Fluctuation: ±2°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Temp. 54–68°F (12–20°C) RH 35–40% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Store instant prints/films away from other photographs due to the escape of chemicals and sharp, sturdy corners with an ability to damage adjacent photos. Store integral instant prints on their sides rather than on end so to prevent dye migration. Acidic and high-alkaline enclosures and/or folders should be avoided. Materials with a pH of 7.0 to 8.5 are recommended. Each print should have its own enclosure to protect it from dust, handling damage, and changes in environmental conditions. This enclosure may be a paper (archival quality) or plastic (uncoated polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, cellulose triacetate) sleeve, envelope, or wrapper. Paper enclosure seams should be along the sides, not down its center. All storage materials should pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT) as specified in ISO Standard 18916:2007.

- Storage Orientation

- Store vertically with dividers between each print. May also be stored horizontally, especially in the case of large prints. Avoid folding and rolling large formats. Enclosures and folders may be stored in hanging files or archival storage boxes. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

Instant Photo, Color

- Synonyms

-

- Internal dye diffusion transfer print

- Polaroid

- Polacolor

- SX-70

- Dates

- 1963 – 2008; limited production persists today

- Surface Sheen

- Glossy

- Paper Fibers

- Not visible

- Image Tone

- Full-color (cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes)

- Description