Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Architectural/Technical Drawing Reproduction: Support Materials

When we talk about support materials, we are talking about the layer that acts as the carrier for the image material and visual information. Here are a few that are typically associated with architectural/technical drawings and reproductions. See the Paper profile for further information.

Paper

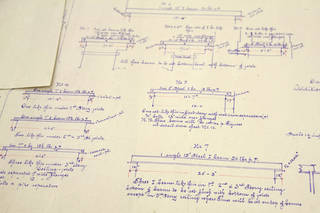

Paper supports of large-scale drawing reproduction will vary to extremes. Regardless of the paper’s function, tracing, or printing, the basic composition is often similar. Semi-translucent tracing paper aided in the professional reproduction of technical drawings before photo-reproductive processes and mechanical and chemical productions began to proliferate in the 1880s. The late 19th century introduced a wide array of surface textures, opacity, and tints. The quality of materials also varied considerably in this period as wood pulp paper emerged as a cheap alternative to rag paper. By 1900, rag paper (cotton, linen) had been pushed to specialty markets, and most paper was made from wood pulp, .

Rag paper has longer fibers, which causes it to stand up better over time than wood pulp paper. Due to the process of machine-pulping, wood pulp paper has short, weak fibers, which become further weakened by common sizing agents (i.e. alum-rosin). Due to a combination of factors (primarily alum-rosin size, lignin, and residual processing chemicals), wood pulp paper produced from 1850 through the 1980s has a tendency to yellow and become extremely brittle over a short amount of time. Exposure to light and/or heat will speed this degradation. As early as the 1930s, the acidic quality of wood pulp paper was widely recognized; and, it has been gradually improved since that time to the point that most papers and sizings are now chemically neutral or alkaline.

Working drawings and prints were often mounted on muslin as a means of strengthening their paper supports. The key degradation factor in such cases will be the adhesive. Masonite, cardboard, and foam-core are also common backings that are usually used in display situations. Of these, masonite and low-quality cardboard are known to damage the paper. If left attached to the backing, the drawing/print will become warped, embrittled, and/or stained in most cases.

Vellum Paper

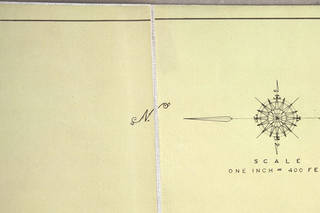

Vellum paper is a stiff or coated semi-transparent paper, not actual animal skin as the name suggests. Specifically, it is a synthetic paper product made from plasticized wood pulp or cotton fibers. Over time, plasticizing agents have shifted from oils to resins to composites. Vellum paper has an ivory or frosted quality. It is semi-translucent relative to its thickness, and it is available in semi-gloss and matte finishes. Vellum paper is a modern support chiefly used for tracing technical drawings, plans, and maps. A thin sheet may be transparent enough to enable light-exposed copies to be created from it. From the 1950s to the early 1980s, vellum paper along with polyester film (Mylar) were predominant materials for reproduction-focused prints and drawings, since they were more dimensionally stable than earlier paper or cloth supports. Vellum paper may also be referred to as vegetable vellum or Japanese vellum.

Vellum paper should be treated similar to drafting paper. Oversize drawings and prints are ideally stored in flat files, as rolling will easily lead to edge tearing. Place them in acid-free and lignin-free folders. Regardless of composition, be sure to interleave these papers with unbuffered, acid-free sheets in order to prevent resins or oils from spreading to others.

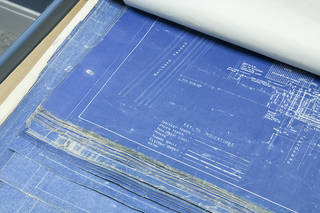

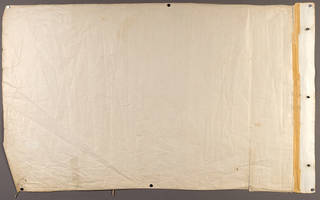

Drafting Cloth

Drafting cloth is among the most common supports found in 19th and early 20th century architectural and technical drawing collections. Introduced in the 1850s, this flexible, durable alternative to paper was used primarily by architects and engineers for process drawings, tracings, and reprographic prints (e.g. blueprints, diazotypes). The fabric is typically cotton or linen, which has been starched and calendered to create a smooth, glossy drawing surface. Over time, additional oil and plasticizer treatments improved translucency and water-resistance in drafting cloths. Prior to the 1880s, cloths had an off-white or natural color; after 1880, a bluish-white tint was common due to a colorant used to increase transparency. Subsequently, blueprinting and similar processes became more popular, as increased translucency enabled more precise photo-reproductions to be struck. Drafting cloth fell out of favor in the mid-20th century after the emergence of synthetic drafting film (e.g. acetate, polyester). Regardless of composition, some people refer to all drafting cloth as drafting linen, or simply "linen."

Since media like pencil and ink rest on the the starch or finish on the surface, the drawing or print should be protected from water and high humidity. Exposure to either element could cause the media to bleed, smear, or migrate.

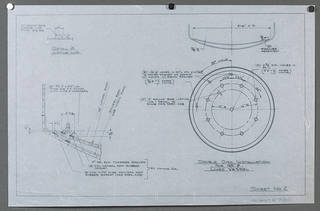

Plastic Film

Plastic drafting film has been used since the 1940s but was a preferred support from the 1980s through the 2000s. Drafting films will have a matte finish on one or both sides, which gives the surface "teeth" to accept media or emulsion. Like other translucent supports, drafting film may be used alternately for original drawings or as a reproductive intermediate. Reproductions were likely run through a diazo machine. Stability will largely depend on composition.

Acetate (1939–present; significant decrease in 1960s)

Early acetates are especially prone to shrinking, and they may exhibit bubbling or "channeling" between layers due to disparate warping. Acetate with "vinegar syndrome" can infect other acetate-based materials stored nearby, particularly in a poorly ventilated storage area. Deterioration is hastened by high relative humidity (RH). If it is suffering from decay, acetate film will emit an vinegar odor. Segregate acetate film in unbuffered paper sleeves, and do not enclose it in polyester sleeves. Reformat if possible.

Polyester, or Mylar (c. 1950–present; popular after 1970)

Debuting in the 1950s, polyester became the standard film material during the 1970s. It cannot be easily torn and is considered chemically inert—despite some reported reaction to the diazo process. If stored in appropriate conditions, polyester may last over 500 years. Some early drafting polyester matte coatings (1950s–1970s) are known to flake; reformat these as soon as possible. Store all polyester film flat in acid-free folders. Interleaving with unbuffered paper may help prevent image transfer or loss. Polyester film is commonly referred to by the trade name Mylar.

Reproductive formats associated with plastic film:

- Electrostatic Prints: Xerox Copy or Laser Print

- Wash-Off Print

- Diazo Print

Resources

- Lowell, W.B. & Nelb, T.R. (2006). Architectural records: Managing design and construction records. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists.