Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Audiocassettes

Unique Content

If what you are assessing is a commercially produced item, more than likely it is not "unique." It may be unique to your archive but, at some point, it was mass produced. Truly unique items often require priority in preservation because they may be the sole remaining document of this material.

First Generation / Master / Original Items

When we talk about "generations" in audiovisual preservation, we're talking about "copies." If something is a second-generation item, it means that it has been copied from the original, or "master." (We should note that sometimes people use the term "master copy," which can be confusing. A master copy is a master.)

The original audiovisual item is the most valuable iteration of the item that you can have, because it should have the best audio and video quality possible when compared to its copies. (This assumes, of course, that the original has been well preserved and is in good shape.) Another reason for giving priority to the original is that it may be the only iteration there is of the item. This means that any damage that occurs to the original could mean that information is lost forever. Even if you have a copy, damage to the master means that you must resort to using copies that may have inferior picture and/or sound.

Following best practice, you should use the master as little as possible and store it in the best conditions possible. Many institutions use their master once to make a "secondary master." This secondary master is then used to make copies for access. Ideally, you should almost never have to return to the master so that it can stay in the best possible storage conditions in perpetuity. If the item you are assessing is a master, then it will be higher in priority for reformatting and preservation than those items which are copies.

Risks of Handling/Playback

Playback and handling are the leading causes of damage to audiovisual items. A film, for example, is most likely to be damaged being fed into or coming off of a projector. Any playback machine, no matter how well maintained, can cause damage to an audiovisual item. That said, it is still best to maintain your playback equipment alongside your audiovisual items. Regular service and cleaning is critical to helping minimize the risks of playback for your materials. An item may sometimes only have one play left before it is permanently damaged, rendering it unusable. If an item must be played back, an operator skilled in handling the playback equipment and at identifying problems with the media prior to playback should be the only person allowed to play the material in question. Allowing media to be handled and played back by untrained staff or patrons is a danger to the material.

Playback Equipment

One of the great challenges of audiovisual preservation is the fact that AV materials require playback machines in order to "decode" the information stored on the materials. This applies to all audiovisual formats. Of course, a further complication is that the playback machine must be appropriate to the format of the AV material. When we consider how many hundreds of AV formats there are, we see that this is a large challenge indeed. The playback machine must also be well-maintained because it can damage the materials fed into it if the machine is in poor repair.

It is important to look at your collection and consider what formats are most valuable to your institution, what formats are accessed the most by your users, and what format you have the most of. These will be the materials that you should have playback equipment for, if at all possible. This can be challenging, but there are avenues you can explore. Local television and radio stations, colleges and universities (particularly those with film, art, communications, or journalism departments), and audio recording studios often have older equipment that they no longer need. As a result, these are excellent places to establish relationships with as you may be able to procure equipment at very reasonable prices. However, keep in mind that universities and colleges often have considerable red tape when selling or donating their equipment, so you should be prepared to invest some time and effort when working with them.

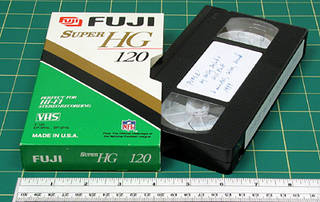

Remember: never put any collections materials into a playback machine without first testing that machine. Have a "dummy" item that you can test a piece of equipment with. For example, you can designate a VHS tape as your dummy tape and use it to test your recently procured and/or serviced VCR. Ideally, this tape should neither be an item that is a part of your collection nor have any value so that it will make no difference if you damage the item.

We do not recommend that you service a piece of playback equipment yourself because of the potential for damage to both the equipment and AV materials. We recommend that you find and establish a relationship with a local repair service. Maintaining your playback equipment should be at least as important as maintaining your collections.

If you do not have (and cannot acquire) playback equipment, it does not mean that the AV materials are without value. In fact, it may be an indicator of higher preservation priority if the playback equipment is obsolete or unavailable to you at your archives. These materials can be especially vulnerable. Film duplication vendors will most likely have the equipment and can transfer the film to a format accessible to your archives.

Remember, if you have materials with no way to play them back, these items will have diminished accessibility. They can end up costing you time, effort, and money when you have to send them out to be transferred to a format for which your institution does have playback equipment. If you plan to digitize your materials, you will have to have well-functioning playback equipment for each format you decide to digitize.

Orientation in Storage

The orientation of a cassette can affect its long-term well-being while in storage. The best orientation for cassettes is vertical and "on edge" .

Audiocassettes and cartridges, generally speaking, like to be stored upright on shelves like books. Piling tapes one upon the other tends to stress the cassettes at the bottom of the stack. This can, over time, cause the plastic housing of the cartridges to warp and even crack, leading to poor playback. Tapes that have been stacked one upon the other for long periods should be closely inspected for cracks and fractures before playback. Storing tapes in their case and upright also helps to protect the cassette within from water damage (since water can flow off the case without pooling inside it) as well as from dust and dirt.

Record Protection Tab Removal

It is very important to copy-protect your cassettes. This is probably the single best thing you should do--and the first thing you should do--to protect your audiocassettes!

With most audiocassettes, the record protection mechanism is simple. This is a piece of plastic that is removed in order to protect your cassette from accidental erasure or copying over while in its playback machine. This should be the first thing you do with your audiocassettes in order to protect them from accidental information loss. If you are assessing a tape and notice that the record protection tab is not removed or in the "save" position, do it now!

The protection tab is in the upper corner of your cassette, opposite the end consisting of the tape path. There is a tab for each side of the cassette. You should remove both of these tabs in order to protect both sides of the cassette.

Audiocassette - Appropriate Container

Containers protect the cassette from dirt, dust, mold, and vermin. These contaminants can damage the surface of the magnetic tape, which can affect its sound quality and even render it unplayable. Ideally, a cassette should be housed in an inert waterproof plastic container. An audiotape's container should be clean and protect the tape's recording surface. Moldy, damaged, and dirty containers should be replaced. The container may provide clues as to how the item has been previously cared for. A dirty, damaged container may be an indication that the tape is in need of preservation care, especially if the container is not providing adequate protection for the tape's recording surface.

If your audiocassette is housed in a plastic container and you're unsure if it is inert or if it is acceptable for preservation purposes, check the condition of the container. If it is protecting the tape from dust, pests, and other contaminants, not shedding or introducing any contaminants through its own degradation, and is clean and free of mold or excessive dirt, the container is acceptable for use. Rehousing to a more expensive inert plastic container is not vital in this case. If the tape is housed in anything other than a hard plastic container (e.g. in a cardboard slipcover) or is not sufficiently protected, it should be rehoused in an inert plastic container.

Labeling

If your item has any kind of labeling on the container, the item itself, or any related material, we highly recommend that you revise the description of this item and enter this information in the notes field.

Unidentified tapes have a tendency to get overlooked or shuffled to the back of the shelf in an institution. Basic information should be recorded on a label both on the tape itself and on the tape's container. Information like title, creator, some kind of alphanumeric identifier (e.g. accession number, catalog number), and some kind of date information (e.g. the date the tape was received, the date the tape was recorded). Bear in mind that describing your materials both on the containers and in a catalog help to keep the materials accessible. When you can't find something, you're less likely to devote time, effort, and funds to its preservation.

Additionally, if you are considering re-housing your tape, you should transfer or retain the labeling and notes (if extant) of the original container. These notes may be helpful to a future researcher.

Physical Damage

Tape Damage

Before playback, thoroughly inspect the tape each time. Look through the cassette window at the quality of the tape wind. Does it seem uneven? Does the tape look twisted within the shell? Look at the tape track. Is the tape rumpled? These may be indicators of physical damage that may not be immediately apparent.

If you load a crumpled or otherwise damaged audiocassette into a deck, you are asking for trouble because you are significantly increasing the odds of the tape being eaten and/or further damaged by the playback machine. Sadly, there are no guarantees that even a pristine tape will not be eaten by a machine--this is why we must preserve playback equipment alongside our media. However, there is no guarantee that even a well maintained machine will not damage an item that is played on it. Exercise caution every time an item is played back. Original materials should rarely, if ever, be played back.

Cassette or Cartridge Damage

Look for the following:

- Cracks and stress fractures

- Dust, dirt, mold, or other contaminant that can affect the tape

A dirty, dusty, or moldy tape transmits filth into the playback machine, impairing it. Look for cracks, stress fractures, dust, and other contaminants on the outer shell of the case. Remember, one of your jobs with regard to audiovisual preservation is to try to ensure the best possible image and/or sound quality during playback.

Mold / Pest Damage

Mold

MOLD CAN BE TOXIC. Proceed with caution when examining tapes for mold. Do not handle moldy tapes longer than necessary. If you find a moldy item, immediately place it and its container in a sealable plastic bag until conservation action can be taken. To check for mold on a audiocassette:

- Inspect the tape container. If you see fuzzy brown, black, white, green, or mustard patches, this is most likely mold. Mold on the container is a good indicator that the mold has traveled to or from the cassette.

- Look through the clear plastic windows or any other area that allows you to see the tape pack on the cassette. Look for black, brown, white, green, or mustard colored fuzzy patches. If you see any, you're most likely looking at mold.

- Look at the tape itself along the tape path for black, brown, white, green, or mustard colored fuzzy patches or fibers at the edge of the tape.

Tapes suspected of being moldy should NOT be played back as the mold can get into the playback machinery and cause poor playback. Mold can also travel onto other tapes so it is best to quarantine any tapes suspected of being moldy. Mold is very difficult to clean off of video and audiotapes, particularly cassette-based tapes, so you're going to have to send these tapes on to professionals for thorough cleaning. This isn't something you're going to want to do in-house.

Following are images of audiotape boxes exhibiting mold. This mold is noticeably darker and splotchier.

Pest Damage

Pests like insects and rodents tend to like paper and textile materials more than audiovisual materials. That said, pests can still do damage to your AV collections. When assessing the exposure of your collections to pests, it is necessary to look not just at the materials themselves and their containers but also at the rest of the environment. Insects and rodents tend to leave droppings in areas they inhabit. Insects tend to leave behind a substance called frass, which is the undigested fibers from paper. If you see droppings and/or frass in your storage area, it is a strong sign that your materials are being exposed to pests. Small, irregular holes on paper-based containers (e.g. sleeves for grooved-disc audio recordings) are also a sign that pests have attacked your materials.

Some tips for reducing your materials' exposure to pests are to refrain from eating anywhere near your collections materials. Crumbs draw rodents and insects, so keep food far from your collections. Another tip is to be careful opening donated materials when you receive them. Pests can hitch rides into your facility on these materials, so having a good, clean staging area where you can inspect donated items for, among other things, pest-related evidence can help you reduce your storage environments' exposure to pests.

Tape Length

Cassettes of longer length have thinner tape, which makes them more susceptible to stretching, snapping, or other damage during playback. Cassettes that are 90 minutes or longer are also more subject to print-through, in which an echo (either pre- or post-) may be heard when the tape is played. Valuable tapes recorded on longer cassettes are a higher preservation risk. Commercially produced pre-recorded audiocassettes are generally 30 minutes in length. Blank, recordable tapes tend to vary more. On blank recordable tapes, lengths are generally indicated somewhere on the cassette shell.

Magnetic Tape Binder Breakdown

a.k.a. Polyurethane Binder Deterioration (Sticky Shed Syndrome / Soft Binder Syndrome)

The material that binds magnetic particles to a base tape film is called the binder. When it comes to magnetic tapes, the polyurethane binder is often considered the weakest link (other than a degrading acetate base) due to an inherent vice broadly referred to as "Soft Binder Syndrome," or specifically as "Sticky Shed Syndrome" if the signal is salvageable. Although polyurethane binders were employed with polyester magnetic tapes from the late 1960s through the late 1970s, it seems that those from the early 1970s through the early 1980s are especially at risk. Binder breakdown will harm not only the recorded media but your playback equipment as well.

- Soft Binder Syndrome (SBS): Richard Hess (2008) recommends this inclusive term be used for all tapes that show stickiness, shedding, and/or squealing, whether they respond to baking or not. This category includes Sticky Shed Syndrome and what has been in the past (incorrectly) referred to as Loss of Lubricant.

- Sticky Shed Syndrome (SSS): A subclass of Soft Binder Syndrome that is treatable through "baking." The most common form of binder breakdown, SSS leaves a dark, gummy residue on playback of back-coated tapes. The shed residue comes from both the binder and the back coating. Attempt to identify SSS before playback.

- "Loss of Lubricant" (LoL): An outmoded but still useful term for a form of SBS. The term is now considered a misnomer since lubricant loss is not actually to blame. The major distinction between LoL and SSS is that the former does not react to incubation. Do not bake tapes identified as having LoL.

Identification

Test for Sticky Shed Syndrome BEFORE attempting playback. To do this, slowly turn the reel, watching to see whether the tape unspools naturally from the pack or whether it sticks/lingers on the pack. The affected tape surface may exhibit a soft and gummy quality and will leave a dark brown residue on tape player components on playback: this is a result of binder and back coating shedding. Do not subject an SSS-affected tape to playback.

Most tapes with SBS will make an audible squealing sound during playback. Other telltale signs of SBS may include jerky and/or slowed tape movement during playback. At its worst, binder breakdown will prevent playback or cause tapes to distort due to high tension from playback.

For more information on binder failure, causes, solutions, known types, and more example images, see Magnetic Tape Binder Breakdown in the Collection ID Guide.

Playback Quality

It is often difficult to truly assess a tape without playing it back. It is entirely possible to have a tape that, to the eye, appears to be in good condition but when played has very bad sound quality. Playback, however, carries with it the risk that your tape could be irrevocably damaged and/or could cause damage to the playback machine. For this reason, we do not recommend playback as a means of assessment. However, if you do play a tape and find that the sound quality is poor, it likely means the tape is in need of reformatting. If this item has been played back recently, there may be notes indicating the playback quality.

Documentation

Having additional documentation about your item can help inform your future preservation decisions. If you have any past documentation about playback or tape quality, this information can be extremely useful in assessing the tape without having to subject it to playback risks. Additionally, documentation may provide evidence of past preservation measures taken on the content or item. You should always document any preservation measures that you take on your materials. This provides evidence to future preservationists and researchers about the path that the content/object has traveled.

Your documentation should NOT be stored with the item. You should store your documentation (e.g. notes written on paper) in a separate physical location. Paper has numerous conservation issues and can be more damaging than helpful. For example, paper can damage your tape by shedding fibers that can abrade the tape surface. If you track your items via electronic means, you may be able to note preservation history in your electronic tracking system and should consider consulting resources on responsible metadata practices.

Audiocassette - Squealing During Playback

Squealing during playback can be a result of a number of things. This could denote problems with the playback machine, especially if many cassettes inserted into the machine exhibit the same problem. It could also be a problem with the tape itself. One common cause of squealing is sticky shed syndrome. Tapes that squeal or make any other abnormal noise during playback should be removed immediately from the playback machine. It is not recommended that you play these tapes back yourself; you should send them to a professional restoration expert to be reformatted. If you determine that the playback machine is the problem, the machine should be serviced before you use it again.

Quality of the Tape Wind

All audio and videotapes should exhibit a tight, even tape pack. This means that when you look at the tape itself, you should not see "windows", or large gaps through the pack. Additionally, if you look at the tape from a slight angle (usually through the clear or translucent window in the cassette), you notice no strands of tape that are standing higher than the rest of the wound tape. These strands of tape are referred to as "popped strands."

A tape will show popped strands if the tape is damaged or warped, if the tape has been stored without being completely rewound or fast-forwarded, or if the playback deck plays, rewinds, or fast-forwards in a less-than-uniform speed. Caution should be exercised when playing back a tape without a uniform tape pack, as it could indicate a problem that will be exacerbated by playing it back--sometimes with disastrous results. Checking the tape pack should be a step taken before playing back any tape.

Many institutions, including the Library of Congress, recommend storing all tapes (audio or video) in the fully fast-forwarded position. This can prevent tape pack issues while the tape is in storage. It will also force you to fully rewind a tape before playing it back (called "exercising" the tape), which can help keep a tape in good shape. Some institutions also create a schedule whereby all tapes that are in good enough condition are taken from the shelf and fully rewound and then fast-forwarded. Making it a point to periodically exercise tapes that are not exhibiting problems can help keep these tapes in good condition.