Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Books and Bound Items

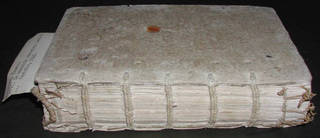

A book consists predominantly of paper and/or parchment leaves, often with assorted isolated components, all of which is sewn or glued together and then attached to a cover. During the early modern period, the textblock was made from large sheets of paper or parchment that were folded down to the desired size. The pages in "quarto" and smaller volumes then had to be cut open in order to be read. Up into the nineteenth century, books were often sold "in sheets," that is, as stacks of folded, printed paper. The buyer would then hire a bookbinder to bind the pages together.

Medieval and early modern books have their cover attached directly to the textblock by sewing, lacing, or cords. Following the development of case binding in the nineteenth century, it became common practice to construct the textblock and its covers separately. The textblock is then "cased in," usually by adhering the front and back sheets of the textblock to the insides of the front and back boards. This technique of book production proved conducive to mass production and continues to the present day.

The extensive history of books and their myriad structures are beyond the scope of the PSAP. The most common structures found in library and archive collections are presented here. The Collection ID Guide and supplemental guides also contain information about commonly used materials that impact the preservation of books and unbound paper.

Binding Types

- Adhesive Bindings ("Perfect," double fan adhesive)

- Sewn Bindings (Through-the-fold, oversewn, stab)

- Other Bindings (Punch-and-bind, stapled)

Board Materials

Cover and Binding Materials

- Cloth (Acrylic-coated, pyroxylin-treated, starch-filled)

- Leather

- Paper

- Tawed Skin

- Vellum / Parchment

General Preservation Concerns

Binding Types

Adhesive Bindings

- Description

-

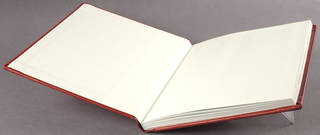

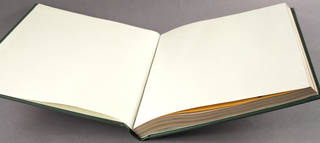

Perfect binding (or, "thermoset adhesive binding") is a type of binding using a hot melt adhesive applied along the spine to hold the pages of the textblock together. Since this method does not allow the adhesive to penetrate between the sheets, it provides a less secure bond than double fan adhesive. While adhesive bindings are generally considered inferior to sewn bindings, they are economical and work well for books that receive heavy use over a short period of time. Mass market paperbacks are an example of this binding type.

"Perfect" binding. "Perfect" binding (inside). "Perfect" binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. "Perfect" binding with staples (inside). Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. -

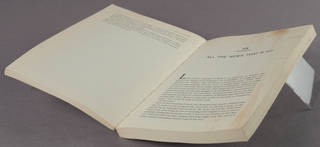

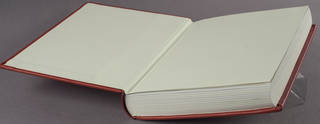

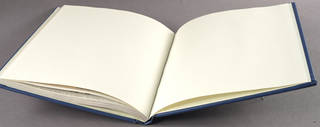

Double fan adhesive binding (DFAB) is a type of binding usually done with polyvinyl acetate (PVA) adhesive. The pages of the textblock are fanned out at an angle on the spine-edge of the book, and adhesive is brushed on. The pages are then fanned out in the opposite direction, and the adhesive is applied again. This procedure provides a secure bond between the pages and results in a binding that lies open flat.

Double fan adhesive binding (DFAB). Double fan adhesive binding (inside). Double fan adhesive binding with non-coated paper (inside). Double fan adhesive binding (bottom) compared to oversewn binding (top). Image courtesy of New York University.

Sewn Bindings

- Description

-

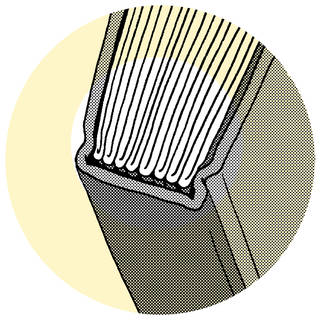

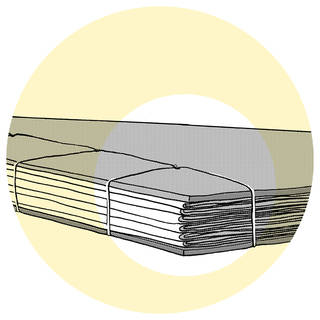

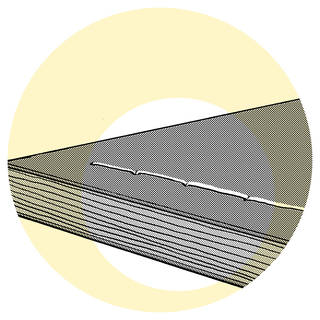

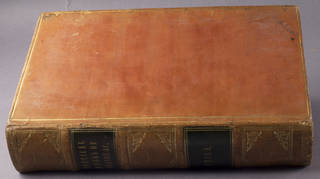

Through-the-fold binding involves sections of pages called signatures, which are arranged and sewn together with thread through holes in the folded edges. The sewing is generally done over either cords, thongs made from animal skins, thongs made of plant fibers (raised or recessed), or tapes (e.g. strips of cloth or vellum) that have been arranged perpendicular to the spine. One of the benefits of this type of binding is that sewing over cords and tapes provides extra support to the textblock. Raised cords create a decorative element on the spine in the form of raised bands. Starting in the nineteenth century, it has now become common for these raised bands to be solely cosmetic additions and not to be an indication of the actual sewing structure beneath. In addition to the sewing, a layer of adhesive is often applied along the spine in order to attach spine linings made of paper, parchment, or textile.

Sewn through the fold. Sewn through the fold. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Handsewn through the fold on tape. Machine-sewn through the fold. -

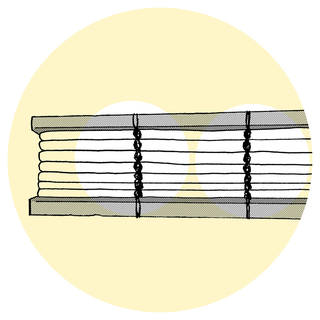

Oversewn binding (or, "library binding") was introduced as a hand-sewn binding technique during the late eighteenth century. Hand oversewing grew as a popular binding for libraries to use to protect their books during the 1900s and 1910s. Oversewing is rarely done by hand anymore, thanks to the development of the oversewing machine by W. Elmo Reavis in 1920. Used almost exclusively by library binders, oversewn binding is intended for large books and those with loose plates. After oversewing, the textblock has about 5/16" removed from the original margin and is tighter in the gutter.

Oversewn binding. Oversewn binding. Spine showing oversewn binding. Image courtesy of New York University. -

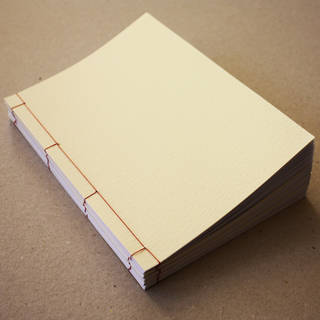

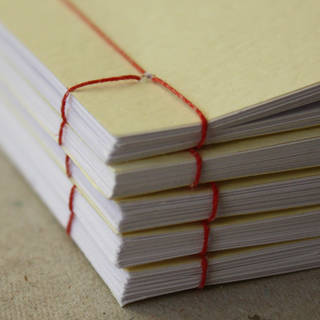

Stab binding (also: Japanese, Chinese, or Korean binding; stitched binding) is an Asian style of sewn binding, which involves punching holes (typically three, five, or six holes) through the textblock along the margin and sewing through to secure the leaves together.

Stab binding. Stab binding. Stab binding. Image by Wikimedia Commons user Leena Kultanen, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license (CC BY-SA 3.0). Book artist: Paul Green, Finland. Stab binding. Image by Flickr user Gareth Morgan, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license (CC BY-NC 2.0). Stab binding. Image by Flickr user Gareth Morgan, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Other Bindings

- Description

-

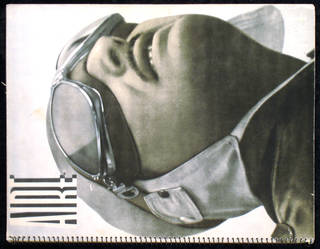

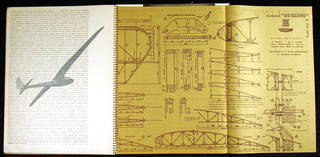

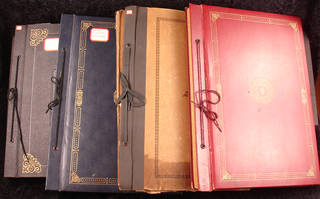

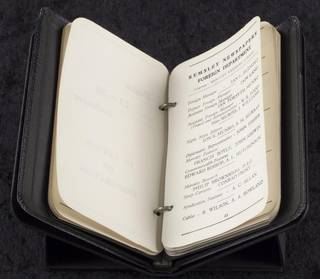

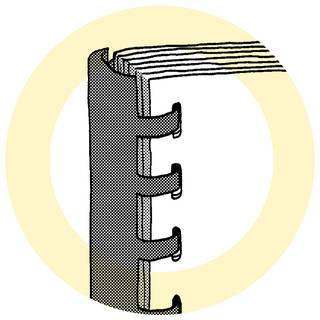

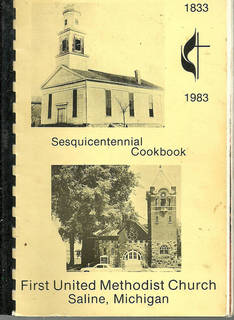

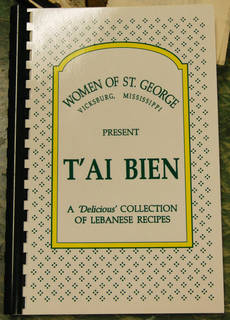

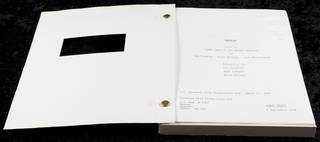

Punch-and-bind binding (also: "VeloBind") involves single sheets being hole-punched or riveted along the spine to allow some form of hardware (e.g. metal pins) to hold the textblock together. In the case of a comb binding for example, a plastic strip with curved prongs secures the sheets through the punched holes. There are many different styles of punch-and-bind binding, including spiral, wire, punch, side-laced, ring, comb, and post. The punch-and-bind method is often used by small businesses and organizations as a cheap and easy binding solution for publications. It is frequently used to bind reports, proceedings, manuals, scrapbooks, and church cookbooks.

Spiral binding. Spiral binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Spiral binding (inside). Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Wire binding. Punch binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Side-laced binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Ring binding (inside). Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Comb binding. Comb binding. Comb binding. Post binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Post binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Post binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. -

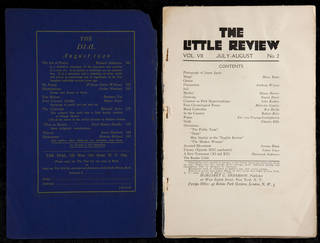

Staples are used in saddle-stitching (center-stapled) and side-stitching. For a saddle-stitched item, staples are driven through the center fold of a signature of pages. Side-stitched pages are loose leafs that have been stapled along the side of the textblock holding the pages together. Staples may rust, causing damage to the item itself and surrounding items.

Stapled bindings: Side-stitch, saddle-stich (outside), saddle-stitch (inside). Side-stitch binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Side-stitch binding (inside). Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Saddle-stitch binding. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Saddle-stitch binding (inside). Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees.

Board Materials

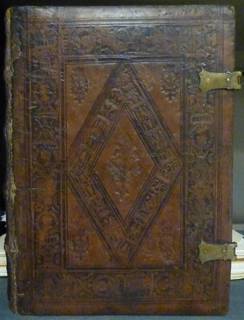

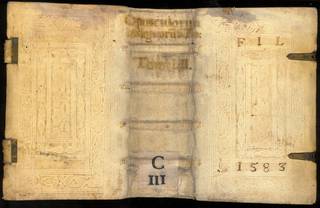

Wood Board

- Description

- Wood board covers are commonly found on books bound prior to 1570. After this date, pasteboards and other types of paper board supplanted wood as primary cover materials in Europe. Wood board covers continued to be used, particularly for school books and bibles, up through the mid-nineteenth century in the United States. Wood boards can be up to one inch thick and were usually made of oak. Scaleboard was a cheap form of book board that was made out of a thin piece of wood (oak, maple, beech, or birch).

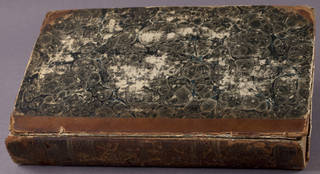

Paper Board

- Description

- Paper boards have been used as support materials for European books since the late sixteenth century. There are many different types of rigid board that are used as book covers: pasteboard, millboard, strawboard, chipboard, laminated board, rag board, davey board, and binder’s board. The materials used to construct different boards can be made of various products ranging from waste paper and rags to wood chips and straw. Early boards, which were made by adhering sheets of paper to one another, were called pasteboards.

Cover and Binding Materials

Cloth

- Description

-

Book cloth came into widespread use around the 1820s. Prior to that, books were primarily bound in leather. Although an array of fabrics (e.g. silk, velvet, and starch-filled muslin) have been used for this purpose—particularly earlier in the nineteenth century, cotton and linen are the most common types of book cloth. Buckram is a sturdy cotton or linen cloth, which is coated and calendared for use as book cloth. Book cloth can also be embossed with different textures and may be made to imitate the texture of leather. There are three main types of book cloth treatments: acrylic-coated, pyroxylin-treated, and starch-filled.

- Acrylic-coated cloth is chemically stable. It is resistant to moisture, mold, and insects.

- Pyroxylin-treated cloth is created with the use of solvents. This process was introduced in the late nineteenth century. It is a sturdy material, although not as chemically stable as starch-filled cloth. Pyroxylin-treated cloth like buckram becomes stiff in low temperatures and may become tacky in high temperatures. It is resistant to moisture and insects, and it can be wiped clean with a damp cloth. Buckram is primarily used as a book covering for circulating library collections and bound journals.

- Starch-filled cloth originally was a colored and sized muslin. Starch-filled cloth is still in use today and is produced by coating cloth with a slurry of water, starch, clay, and pigment. It is chemically stable but not durable. It is susceptible to insect damage, mold, water spotting, and soiling.

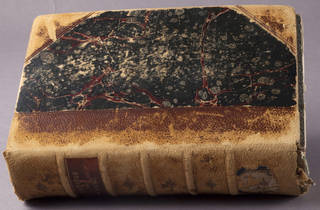

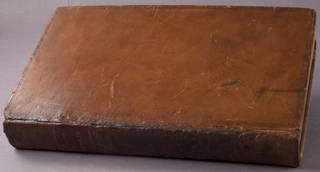

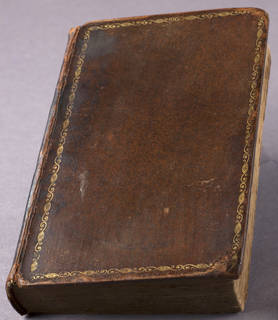

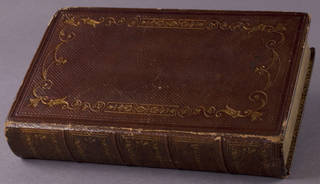

Leather

- Description

-

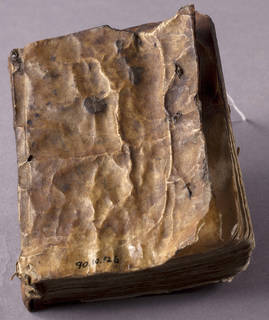

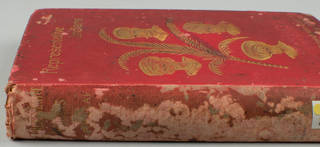

Book-binding leather is most often made out of calf-, goat-, pig-, or sheepskin. Different leathers have varying durability, but they should be treated the same in terms of preservation. The leather is prepared first by removing animal hair from the skin either mechanically or with chemicals and then by processing the skin through tanning. Leather produced throughout the sixteenth century is generally stable and often found in good condition due to the slow tanning process, which resulted in leather that was resistant to decay and acid deterioration. As demand for books grew in the seventeenth century, so too did the demand for leather. In fact, leather was the most common book-covering material until the nineteenth century; and, it continues to be used today.

Books with slight leather components are sometimes inaccurately referred to as "leather bound." Here are more specific terms regarding the ratio of cover and spine materials: "Full binding" means that the cover and spine is covered in one material (e.g. leather); "half binding" indicates that one material is split across the spine and only slightly across the sides at roughly a 1:1 ratio to another binding material (e.g. leather and muslin); and, "quarter binding" means that only the spine is covered in one particular material and that it is at a 1:3 ratio to another binding material.

Split leather: Leather, particularly that which is used in bookbinding, has often been split in order to thin the top-grain by separating it from its underside. This "drop split" may be used to produce suede, which is a type of leather often used to bind books in the nineteenth century. Suede is produced from the underside of softer animal skins (lamb, goat, calf) or produced through splitting the hides of thicker cow or deer skins. As it does not include the exterior skin layer, suede is therefore softer, less durable, and more susceptible to staining and water damage than full-grain leather.

Leather from the nineteenth century will often deteriorate quickly due to the aggressive chemicals used to speed up the tanning process. All leather is inherently acidic, but excessive acidity in combination with exposure to atmospheric pollutants may result in "red rot," a form of leather decomposition that appears soft and will crumble into a reddish-brown powder. Historically, leather dressings have been applied to leather bindings with the intention of preserving the leather’s surface and suppleness. However, recent research may suggest that these dressings likely do not provide any noticeable preservative effect to leather bindings.

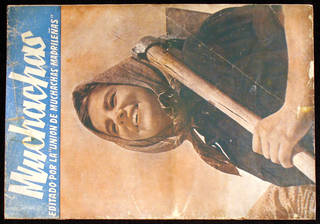

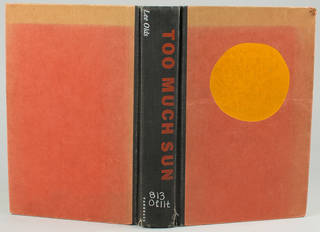

Paper

- Description

- Paper covers may be made with coated or uncoated paper of many different types. For more on different types of bound paper, see Paper.

Tawed Skin

- Description

- Tawed skin is not tanned, which differentiates it from leather. Tawed skin, which is usually either pigskin or goatskin, is first preserved using solutions of alum, salt, and sometimes other materials like egg yolk or flour. The skin is then air-dried and flexed over a blade to soften it. The result is a tough, flexible, white skin. It was used most frequently for seventeenth and eighteenth century books.

Vellum/ Parchment

- Description

- For a complete profile of the use of animal skin in book production, see Parchment.

General Preservation Concerns

- Deterioration

-

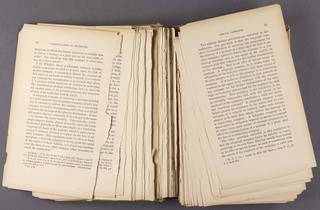

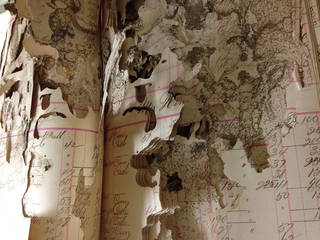

The deterioration of a book or any bound item will greatly depend on the materials used to make it. This means that you must consider the cover and binding materials of the book as well as the types of paper and ink used for the textblock. The adhesives binding pages together can deteriorate over time and cause the binding to weaken or come apart. Rubber-based and animal hide glues are particularly unstable. Factors like temperature, relative humidity (RH), and environmental pollutants may cause paper and other materials used in the binding to deteriorate. Fluctuating temperature and RH cause paper to swell and contract, which puts stress on the binding and covers. This stress may manifest in the forms of cockling, deformed covers, or loose binding. High heat will accelerate deterioration and cause paper to become yellow and brittle. An environment with a stable temperature below 65°F and relative humidity between 35–45% will both preserve items and help prevent pest infestation and mold.

Mold may develop on items stored in a warm, damp environment. Fluctuating temperature and RH may also cause mold to bloom. Mold can leave staining, even when it is no longer active. Pests--particularly silverfish, cockroaches, and rodents--may cause physical damage or stain cover material and pages.

Mishandling and heavy use may cause damage or soiling. Common forms of this type of damage include broken hinges, torn headcaps, loosened sewing, and folded or creased pages. Book cradles should be available so books are not opened too far, putting stress on the sewn or glued binding.

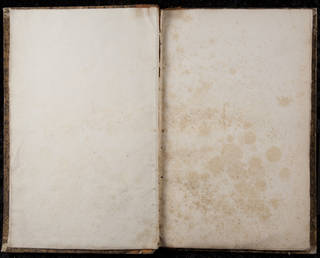

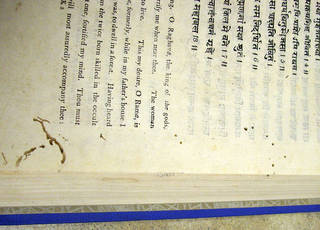

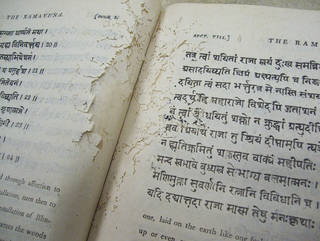

Foxing is a common form of paper deterioration that is frequently seen in books. Although the exact causes of foxing are varied and not easily identified, it is often the result of high humidity combined with fungal growth or metal impurities present in the paper. Foxing will appear as reddish-brown (rusty) flecks on the paper. They can appear across the surface or can be situated in clusters in either "bullseye" (small and round, dark center) or "snowflake" (larger, irregularly shaped blotches) shapes.

Red rot is a type of deterioration particular to leather. It is common in leather bindings produced in the nineteenth century. The exact cause of red rot is unknown, but it is believed to be the result of acidic residue in the leather reacting to poor environmental conditions (pollutants and high heat especially). Red rotted leather is characterized as soft, powdery leather that crumbles into a reddish brown powder. There is no way to reverse this deterioration, but the leather can be consolidated so it does not crumble further. Consult a conservator before applying consolidants to objects. An alternative treatment, which does not stop the red rot but contains it for easier handling, is to cover the book in a polyethylene sleeve or wrap it in acid-free paper.

- Storage Recommendations

-

Books should be stored upright on the tail edge. They should be gently supported, not tightly crammed onto shelves or allowed to slump or sit at an angle. If a book is too tall to fit on the shelf, it should be stored upright on its spine or laid horizontally flat. A book should never be stored on its fore-edge: the weight of the textblock is pulled away from the spine and may cause the hinges to loosen or break.

If possible, books of similar size should be shelved together so that they are equally supported on both sides.

When removing a book from the shelf, grip it on both sides of the spine near the middle of the book and slide it out from the shelf. Do not pull a book from the shelf by the headcap: it may loosen, break, or cause the spine to tear.

Regular housekeeping, which includes dusting and wiping down shelves as well as collection materials, prevents the accumulation of dirt and debris on and around collection materials as necessary. Dust absorbs and holds moisture, which promotes mold growth, pest damage, and accelerates deterioration.

Dark storage is best if possible, and lights should be turned off in storage areas when patrons and staff are not present. UV filters should be applied on fluorescent light tubes and windows in these areas.

If possible, shelves should not be butted up directly against outside walls and should be placed away from radiators, vents, and other areas where temperature or RH fluctuate.

- Storage Furniture

- Store on metal shelves, preferably powder-coated steel or chrome-plated steel shelves and components. Avoid wood. If wood is unavoidable, make certain that it is properly sealed to reduce these gaseous emissions. Avoid oil-based sealants and paints. Always elect for non-toxic or low VOC (volatile organic compound) sealants and paints if available. Recommended sealants include water-based polyurethane or two-part epoxy sealant.

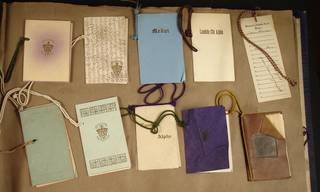

- Storage Enclosures

- Valuable or very fragile books may require their own enclosures. Depending on the condition and value of the item, this can be as simple as wrapping them in paper or as complex as providing them with a custom clamshell box. These custom boxes may be constructed in-house using archival (acid-free) materials that are available through many archival supply companies.

- Storage Environment

-

Cool storage (below 50 degrees) is recommended, and colder is generally better. Allowable Fluctuation: ±5°F; ±5% RH

Based on ISO 18920Ideal Temp. 35–65°F (2–18°C) RH 35–50% RH - Display Recommendations

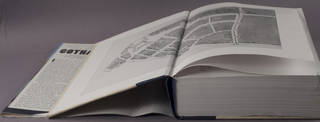

- Books and pamphlets should be displayed horizontally or at a gentle angle. Do not display an open book beyond its comfort angle, generally 30–45°. Anything else may cause warping or weakened binding. Books on display should have their pages turned at regular intervals so to prevent overexposing any single spread to light. Turning the pages also helps prevent damage to the binding from leaving it open at a single point, which puts undue stress on that part of the spine.

Resources

- Glaser, M.T. (n.d.). Protecting paper and book collections during exhibition. Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center. Retrieved from: http://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/2.-the-environment/2.5-protecting-paper-and-book-collections-during-exhibition

- ISO. (2000). 18920 Imaging materials–Processed photographic reflection prints–Storage practices.

- McCrady, E. & Raphael, T. (1993). Leather dressing: to dress or not to dress. Conserve O Gram, 9(1). National Archives (U.K.) (n.d.). How to deal with red-rotted bindings. Retrieved from: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/preservation/faq/redrot.html

- Miller, J. (2010). Books will speak plain: A handbook for identifying and describing historical bindings. Ann Arbor, MI: The Legacy Press.

- Nicholson, C. (1992). What exhibits can do to your collection. Restaurator, 13(3), 95–113.

- Ritzenthaler, M. L. (1983). Archives & manuscripts: Conservation, a manual on physical care and management. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists (SAA Basic Manual Series). [ISO 18920]

- Ritzenthaler, M.L. (2010). Creating a preservation environment. In Preserving Archives and Manuscripts (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The Society of American Archivists.

- For additional resources, see Adhesives, Books & Paper (General), and Leather & Parchment.