Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Museum Objects in General

To meet the broad needs of its users with varied collections, the PSAP is has expanded its scope to include common cultural heritage objects, and now covers four types of inorganic object materials often found in libraries, archives, and museums: ceramic, glass, stone, and metal. The term “object” refers to three dimensional materials outside the realm of audiovisual, photographic and image, and paper and book materials. The essentials of preservation for objects are similar to those for previously covered PSAP materials in that control of environmental factors is crucial. However, because of material type, size, shape, and other differences, the approach regarding storage, display, and handling of museum objects raise different preservation concerns.

While the PSAP now covers ceramic, glass, stone, and metal objects, this module of the PSAP will not address issues surrounding architectural objects such as stone foundations, bricks, masonry, glass or mica windows, composite windows such as lead-lined stained glass, siding, plumbing or electrical wiring. Composite objects that are made of more than one type of material will also not be addressed at this time, as preservation assessment and needs become complicated when multiple materials exist on one object. For example, a glass-and-metal object cannot be treated as though it were solely glass or solely metal, as the two materials can react differently in different environments-- creating additional concerns for care, handling, and storage.

Note that the term “objects” comprises a wide variety of material types even within the categories of ceramic, stone, glass and metal. As a result, the goal of the PSAP is not to provide identification and preservation information for every potential sub-type within each broad material category (for instance, distinctions between granite and gabbro or other similar types of stone). As the condition of an object often creates the greatest challenges for preservation, the PSAP’s Collection ID Guide and assessment tool try to provide users with the information they need to identify whether a material/object is stable or unstable, rather than with specific details on the characteristics of each sub-type of material. The questions used for item and collection assessment are designed to uncover clues as to the broad preservation stability or instability of that item. More detailed information about specific materials and some material sub-types can be found in the CIDG material sections and in Advanced Help.

- Is it glass, stone, or ceramic?

- Object Surfaces

- Previous Residue

- Previous Repairs

- Storage of Objects

- Handling Objects

- Labeling Objects

- Displaying Objects

- Archaeological Objects

Is it glass, stone, or ceramic?

While it is often easy to tell what kind of material an object is made of, sometimes it can be difficult to discern if an object is made of glass vs. stone, or ceramic vs. glass, etc. Typically, if an object is transparent, it is probably glass. If it is translucent or semi-transparent, it is likely either glass or porcelain (as other ceramics and most types of stone do not allow light to pass through). Stone is considerably more dense, and is typically a poor insulator (thus feels colder to the touch) than ceramic. Many stone objects in collections are from archaeological sites.

Object Surfaces

It is important to note that common museum objects will have a wide variety of surface strengths and porosities. However, soft, porous items are at higher risk for surface damage than hard, non-porous items. Soft surfaces can be damaged with even minor jostling, so iems with soft surfaces must be carefully packed and stored to avoid unnecessary breakage. All materials in a collection should be kept from accumulating dust. Dust is hygroscopic and will attract additional dust and dirt that can damage or stain materials. Soft, porous materials like alabaster and terracotta, for example, easily absorb dirt and dust, so they are more susceptible to staining and damage from moisture, dirt, and dust. Hard, and non-porous items are less likely to absorb dirt and dust, and are typically easier to keep clean.

Ideally, items will be protected from dust while in storage and display. To protect items from dust: larger objects on shelves should either be in a cabinet with gasketed doors or have a dust barrier made of clear plastic (polyethylene) or unbleached cotton. You may attach dust barrier sheets to shelving with either magnets or binder clips. At very least: basic dusting and housekeeping –will help prevent further dust and corrosion problems. Dust can be removed from stable objects by gentle brushing and regular dusting. If an object is seen to be accumulating dust you may gently use a HEPA museum vacuum to remove dust particles 0.3 microns or larger. If you don’t have one, you might be able to borrow one from a nearby museum.

Previous Residue

Visible residue from previous use or accumulated material on the surface of an item should not be cleaned or removed, even to view the surface beneath. These residues may be useful for purposes of research and, if removed, can harm or seriously destabilize the object. An expert should be consulted if removal of previous residue is considered absolutely necessary.

Residue might take the form of active corrosion or damage. If this is the case, place the item in a microclimate (container) to slow deterioration and talk to a conservator about ways to prevent further deterioration. Residue from functional use, such as melted wax on candlesticks, is often preserved to secure the historical value of that item, but is occasionally removed by a conservation professional at the discretion of the institution. Cleaning museum objects is rarely recommended for non-experts, as damage often occurs as a result of inadvertent mishandling during cleaning. However, accumulated dust should be removed so that it does not cause further damage to an object.

Previous Repairs

Objects may show signs of previous repair. Most repairs will be evident under blacklight (UV), but many will also be visible to the naked eye. Materials used for previous repairs may have become unstable: old adhesives can discolor or become brittle, and metal or wooden splints and staples used to hold breaks may have degraded. Objects with previous repairs should be treated as highly fragile --- not only has the stability of an item been compromised by the original break, but aging adhesives, staples, and other fillers such as plaster of paris can continue to endanger the stability of the object. Degraded previous repairs can also stain or otherwise damage nearby materials, including other artifacts. Consult a conservator if you are concerned about the stability of a previous repair. Never attempt to reverse previous repairs without the assistance of an expert! More Information about adhesives can be found in the Collection ID Guide.

Storage of Objects

While there is some overlap in the storage needs of library, archives, and museum materials, the fact that museum objects can vary widely in size, shape, and weight, sometimes makes storage of objects more challenging. In general, objects should not be stored on shelving made of uncoated wood or anything that will off-gas. Shelves, cabinets, and other storage furniture should be far away from high-traffic areas, and they they should be in areas of the building that are not susceptible to vibration. Storage areas and shelving should not be near doors, windows, vents, pipes. heating units, or anything else that could cause a fluctuation in temperature or RH, or that could create a leak. Storage areas should be kept clean and free of dust. Shelves should not wobble and drawers should have safety mechanisms so they cannot slide out all the way. Because objects can be heavy, care must be taken to ensure that shelving can support their weight.

On the shelves and inside cabinets, there should be buffer layer between the shelf and the objects, a layer of acid-free tissue paper or polyethylene, for example. Items should be placed on shelves at safe distances from each other, so that access to each item is not impeded. Objects should not be stacked unless absolutely necessary. If stacking is unavoidable, a layer of inert foam or acid-free tissue should be placed in between objects to avoid damage from contact. Lids, pedestals, and other removable parts should be stored next to their items. Heavy objects should only be stored on shelves that are easily accessible -- ideally at waist- or cart-level, so that they are less difficult to retrieve from shelves. If open shelving is being used for object storage, items can be placed in archival boxes or acid-free tissue can be draped or wrapped around items to minimize dust accumulation and reduce the need for cleaning. Never let the width of an object protrude past the width of a shelf. Do not store large items that do not fit on the shelves directly on the floor -- use risers to prevent the item from coming in contact with the floor.

Supports and cushions can also be used to protect and prevent items from moving or tipping in storage. Supports can be fashioned from polyethylene foam or acid-free tissue. Adequate cushions can be made out of materials as simple as styrofoam packing peanuts in a plastic bag. Using supports underneath flat, oversize, or awkwardly-shaped objects can help handlers get a better grip underneath flat objects. Placing individual objects in trays made from archival-grade paperboard can also make it easier to move items in and out of storage. Smaller items can also be stored in 2 mil or 4 mil polyethylene ziploc bags (fragments, particularly glass fragments, should always be kept in 4 ml reclosable polyethylene bags or boxes to minimize the risks of their causing damage to other objects.

Handling Objects

It is best to handle fragile objects as little as possible. When handling is unavoidable make sure that hands are clean and dry and wear the appropriate gloves. (Read more about gloves in Handling & Preparation of the Exhibit Guidelines in the User Manual). Remove jewelry and accessories, including anything hanging around the neck or clothes that may inadvertently come into contact with and damage materials, such as: necklaces, headphones, nametags, scarves, bracelets, and loose sleeves. Take note of any damage, deterioration, previous repairs, vulnerabilities before handling objects. During handling, pick an item up underneath its center of gravity, never by its protruding elements (even if that protuberance is a handle). Artifacts should never be handed from one person to another, but placed on a flat, stable surface so that a second person can pick it up. Before picking up an item, remove any additional pieces, such as lids and pedestals, and carry those pieces separately. If objects are being transported more than a couple of feet, it is best to use a cart with proper padding and stabilization for the items on the cart.

Labeling Objects

Museum objects and each of their removable parts should be individually labeled. Even when working with small objects, resist the urge to label groups rather than individual items. Each item should be labeled individually rather than just labeling the larger bag or box containing the artifacts.

Labels should be durable, removable/reversible, and should not cause damage to the object. Never use permanent labeling techniques (i.e., etching or engraving) or pressure sensitive tape or stickers to label materials! Artifact labels should always be made or applied with approved materials -- different types of artifacts may require different labels. Typically, the best method of labeling basic museum object materials is to apply a barrier coat of B-72 lacquer, upon which a label (on acid-free paper) is applied or the number is directly written on the barrier coat with permanent ink. A top coat of B-72 lacquer is then applied to protect the label. If the surface of an object is too fragile or damaged (covered in a layer of corrosion, for example), an acid-free paper tag with a cotton string can be carefully tied to the item. If objects are too small to mark directly, they can be placed in a small container (polyethylene bag or acid-free envelope) and the container can be marked with a label.

Keep old labels - they are part of the object’s record and should be retained with the object (ie. in a reclosable bag with the object) or in the object or donor file. Even if you believe old labels are inaccurate, they should be retained as part of the object’s record.

Displaying Objects

Placing objects on display increases their risk of deterioration and damage. Objects should be adequately mounted and supported during exhibit. Some sources recommend using museum wax to affix items to their pedestals or exhibit displays, but wax may stain or leave an imprint on porous objects, including porous ceramics and stone. Instead of using museum wax, the best thing to do is provide proper support for the object using inert museum and archival quality materials. In addition to offering protection from dirt, dust, and other pollutants, exhibit enclosures should also create a physical barrier between objects and the public (to protect from being touched and also to keep secure). Never allow objects on display to come in direct contact with the floor - mount objects so they are lifted off the floor. Care should be taken with exhibit lighting and UV filters should be used to protect objects from undue light exposure. Avoid extended exposure to direct light by regulating light levels in an exhibit space and limiting the length of time an object is on exhibit. Read more in Exhibition Guidelines in the PSAP User Manual.

Archaeological Objects

Archaeological objects or fragments that were at one point buried, are generally considered less stable than non-archaeological items. Deterioration occurred during burial and exposure to soil, water, insects, mammals, roots, etc. Excavation and adjustment to a new environment also may add to deterioration. Evidence of damage includes salt deposits on ceramic and stone, iridescence on glass, and thick corrosion of various colors on metal. Archaeological items are more likely to degrade and should not be cleaned or dusted without consulting an expert. All objects believed to be archaeological should be treated with utmost care.

- Soluble Salts and Archaeological Materials

-

When objects are buried and exposed to water, salts can become deposited in the pores of the body of an object. Porous ceramics and stone that have been buried often contain soluble salts, which are found in both groundwater and seawater. Soluble salts dissolve when exposed to moisture in the air (a process called deliquescence). As a result, these salts can move through the porous body of an object, crystallizing at or just below the surface. As salts crystallize on or near the surface of an object, they can break or crack the surface of the object. Soluble salts produce what appears as a white growth on the surface of objects, particularly along cracks or abraded areas. As salts continue to crystallize, they will take on a look of white powder or salt crystals on the surface.

Changes in RH will trigger the movement of soluble salts in and out of porous object materials. In addition, salts can form on objects when object materials chemically react with acids released from wood or paints in certain storage materials. Storing an object in an environment or microclimate with a stable RH can help prevent deterioration caused by the movement of soluble salts. Desalinating objects is not recommended, since desalination treatment can cause additional damage. Consult an expert or conservator if you want more information about halting salt deterioration occurring on objects in your collection.

Unlike soluble salts, insoluble salts take a much longer time to dissolve in water. Insoluble salts are not deliquescent, and will not cause the same post-excavation damage as soluble salts. But insoluble salts can still be disfiguring: they can contain contaminants from the soil that can obscure the surface of an artifact. Insoluble salts can make an object surface appear bumpy, uneven, or muddy.

-

Terracotta bowl (low-fired ceramic) with efflorescence from soluble salts. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Earthenware pot (low-fired ceramic) with efflorescence from soluble salts. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. - Archaeological stone

-

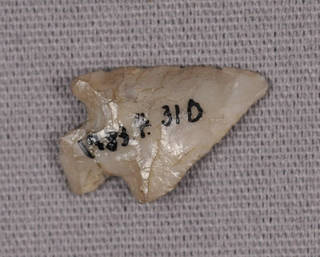

Can typically be grouped into two general categories: chipped stone and ground stone. Storage and exhibit environments are almost identical for objects in either category, but to avoid damage, groundstone and chipped stone should not be stored together in the same container. Read more about types of stone, including types of archaeological stone, in Stone of the Object Materials page in the Collection ID Guide.

-

Chert projectile point. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Limestone discoidal stone tool. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. - Archaeological ceramics

-

Buried ceramics, particularly those with high porosity, are more likely to show signs of salt efflorescence or spalling (substantial flaking) than non-archaeological ceramics. Read more about types of ceramics in Ceramics of the Object Materials page in the Collection ID Guide.

-

Archaeological ceramics. Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. Archaeological ceramics. Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. - Archaeological glass

-

Glass that has been buried often exhibits signs of iridescence-- rainbow-colored, shiny, and flaky layers on the surface as a result of its exposure to moisture. Archaeological glass is also more likely to develop dulling or frosting, in which previously clear glass turns cloudy or shows a network of cracks that appear like patterns of frost on a window. However archaeological glass that has been maintained in a cool, dry environment may not immediately show signs of weathering. Read more in Glass of the Object Materials page in the Collection ID Guide.

Obsidian, a shiny igneous rock, is considered “volcanic glass” and is often found in archaeological environments. For more information on obsidian, see Type of stones.

-

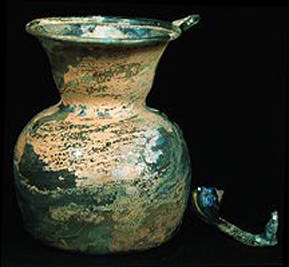

Archaeological Roman glass pitcher with broken handle and iridescence. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Piece of archaeological glass (the bottom of a bottle) with iridescence. Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. - Archaeological metals

Metals that have been buried will be corroded with either thick layers that form a crust on the surface of the metal, or thinner more regular layers of corrosion. Typical archaeological metals include iron (wrought and cast), copper and copper alloys (brass and bronze), zinc, lead, and tin. The type and color of corrosion may give clues as to the type of metal beneath (e,g., copper corrosion is typically blue/green, while iron corrosion is usually yellow/brown/orange in color). Read more about types of meta Metal of the Object Materials page in the Collection ID Guide.

-

Archaeological metal nails (probably iron). Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. Archaeological metal post (probably iron). Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. - Storing Archaeological Materials

-

It is best to house archaeological stone objects in separate containers, preferably acid-free small boxes with padding if necessary. Small, 2 mil or 4 mil polyethylene reclosable bags may also be used. If it is necessary to house collections of stone objects, such as archaeological arrowheads in the same box, be sure to place chipped stone and groundstone objects into different containers. The denser, heavier and larger groundstone objects may damage the chipped stone objects, especially if you are using bags and they are touching each other. Chipped stone objects are prone to chipping (which is why they were chosen for artifact manufacture), and will likely chip and/or break if stored loose in a box with other objects. As with other objects, constant RH and temperature is important for archaeological materials, which are more sensitive to environmental changes.

Many regional museums receive donations of archaeological artifacts from private local collectors. These collections are often housed inappropriately: archaeological objects are stored loosely in a single box or housed in portable “exhibit boxes.” Such cases are often made of wood and glass, and/or lined with foam that is not “archival” (and may off-gas). If archaeological collections are received in these types of improper housings, at the very least the artifacts should be removed from the detrimental environments and individually stored inside archival quality boxes or containers. The glue used to affix items inside “exhibit boxes” is sometimes hard to remove, and some bits of backing can adhere to objects. Consult an expert or conservator regarding glue removal in order to prevent any further damage to archaeological objects.

As with all other objects, do not discard any old labeling, even if you believe it to be in error. Old labels can be stored in a separate container, such as a reclosable plastic bag, if you think they are causing damage to the objects.

-

Wood "exhibit boxes" are improper enclosures - they are made of wood and non-archival foam (which off-gas). Courtesy of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, University of Illinois. Small items or fragments can be stored in polyethylene re-closable bags. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Resources

- Canadian Conservation Institute. (2002). General precautions for storage areas. CCI Notes, 1/1. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Conservation Institute. Retrieved from: http://canada.pch.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-PCH2-Museology-PreservConserv/STAGING/texte-text/1-1_1439925169944_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=4.4.10

- Canadian Conservation Institute. (2006). CCI notes/Notes de l’ICC. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Conservation Institute.

- Caple, C. (2011). Preventative conservation in museums. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chicora Foundation. (1994). Managing: The museum environment. Columbia, SC: Chicora Foundation.

- Knapp, A.M. (1993). Preservation of museum collections. Conserve O Gram, 1/1. Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/01-01.pdf

- Ogden, S. (2004). Caring for American Indian objects: A practical and cultural guide. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Johnson, J.S. (1998). Soluble salts and deterioration of archaeological materials. Conserve O Gram, 6/5. Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/06-05.pdf

- Logan, J. (2007). Identifying archaeological metal. CCI Notes, 4/1. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Conservation Institute. Retrieved from: http://canada.pch.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-PCH2-Museology-PreservConserv/STAGING/texte-text/4-1_1439925170180_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=4.4.10

- National Park Service. (2001). Appendix I: Curatorial care of archaeological objects. In NPS museum handbook, part I: Museum collections (pp. I:1-I:15). Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/MHI/AppendI.pdf

- For additional resources, see Objects (General) and Archaeological Objects.