Preservation Self-Assessment Program

Ceramic

Risks of Handling / Use / Display

Handling of any kind (including for research use or display purposes) puts objects at risk. In addition to being handled as little as possible, the time that objects are on display should be limited.

When handling is unavoidable, steps should be taken to make sure that proper handling methods are in use, including the use of appropriate gloves. Ensure that staff, volunteers, and patrons are adequately trained in handling collection materials. Take note of any damage, deterioration, previous repairs, or other vulnerabilities before handling objects. During handling, pick an item up underneath its center of gravity, never by its protruding elements (even if that protuberance is a handle). Before picking up an item, remove any additional pieces such as lids and pedestals, and carry those pieces separately. If objects are being transported more than a couple of feet, it is best to use a cart with proper padding and stabilization for the items on the cart.

Placing objects on display increases their risk of deterioration and damage. In addition to offering protection from dirt, dust, and other pollutants, exhibit enclosures should also create a physical barrier between objects and the public (to protect objects from being touched and to keep objects secure). Never allow objects on display to come in direct contact with the floor - mount objects so they are lifted off the floor. Care should be taken with exhibit lighting, and UV filters should be used to protect objects from undue light exposure. Avoid extended exposure to direct light by regulating light levels in an exhibit space and limiting the length of time an object is on exhibit. Whether on display or in storage, objects should be properly supported using inert and acid-free support materials. To learn more about handling, use, and display see the Use and Access and Exhibition Guidelines sections of the PSAP User Manual in the Collection ID Guide.

Exhibiting Objects

There is always some level of risk involved with placing objects on display, even if only for a limited time. In addition to ensuring that an item on exhibit is properly supported and secure, other considerations include maintaining good environmental conditions in exhibit spaces and protecting objects from excessive light exposure while they are on display. Objects should be adequately mounted and supported during exhibit. Some sources recommend using museum wax to affix items to their pedestals or exhibit displays, but wax may stain or leave an imprint on porous objects, including porous ceramics and stone. Instead of using museum wax, the best thing to do is provide proper support for the object using inert museum and archival quality materials. In addition to offering protection from dirt, dust, and other pollutants, exhibit enclosures should also create a physical barrier between objects and the public (to protect from being touched and also to keep secure). Never allow objects on display to come in direct contact with the floor - mount objects so they are lifted off the floor.

Care should be taken with exhibit lighting and UV filters should be used to protect objects from undue light exposure. Light damage is irreversible and accumulates gradually, so extended exposure to direct light must be avoided. Lighting levels in exhibit spaces should be regulated, and the length of time an object is on exhibit should be limited. When on display, objects should be protected from exposure to natural light, which contains high levels of UV radiation. Shades, curtains, or filters applied directly to windows will help to minimize sunlight. Natural light, fluorescents, and halogen lamps produce high UV radiation and will require filtering. Lighting should never be placed inside a display case, as it can create dangerous levels of light and heat for objects. It is wise to take the time to measure UV light intensity in a given space.

Items on display are particularly vulnerable to theft. It is necessary to modify displays and exhibits to minimize risk. At the very least, any valuable or rare items (particularly those that are easily picked up and transported) should be secured in locked cases/enclosures. To learn more about the risks associated with exhibiting objects, see the Exhibition Guidelines section of the PSAP User Manual in the Collection ID Guide.

Catalog Record / Photographs

Having good descriptive data and/or photographs of objects can reduce or eliminate researchers’ need to handle items, which will greatly reduce the risks to the objects. Detailed cataloging and photographs also help make materials searchable for administrative and collection development purposes. Without descriptive data capturing key characteristics, all materials are at greater risk of misidentification, misplacement, and improper care. Undocumented or poorly described collections can be especially vulnerable to theft, neglect, deterioration, improper storage, and deaccessioning. To learn more about the benefits of using a detailed catalog record, see the Use and Access section of the PSAP User Manual in the Collection ID Guide.

Training

Training staff, volunteers, and even patrons on how to properly handle object materials is an important way to reduce possible damage associated with mishandling. In general, it is best to teach staff that fragile objects should be handled as little as possible. When handling is unavoidable hands should be clean and dry, and the appropriate gloves should be worn. Jewelry, accessories, or anything hanging around the neck or on clothing that could inadvertently come into contact with and damage materials should be removed or secured. Take note of any damage, deterioration, previous repairs, vulnerabilities before handling objects. During handling, pick an item up underneath its center of gravity, never by its protruding elements (even if that protuberance is a handle). Artifacts should never be handed from one person to another, but placed on a flat, stable surface so that a second person can pick it up. Before picking up an item, remove any additional pieces, such as lids and pedestals, and carry those pieces separately. If objects are being transported more than a couple of feet, it is best to use a cart with proper padding and stabilization for the items on the cart. To learn more about proper handling of objects, see Handling Objects in the Museum Objects in General section of the Collection ID Guide.

Gloves

Different gloves are appropriate for different types of object materials, depending on the surface and softness of that material. If handling slippery and/or fragile glass or ceramic objects, nitrile and vinyl gloves are recommended over cotton gloves. If the glass or ceramic object is stable and not soft, cotton gloves with friction dots can help improve grip. Fingerprints can stain metals, so it is absolutely necessary to wear gloves of some kind when handling metal objects! It is always best to use clean gloves that fit and are free of holes or tears.

Consider the following when selecting gloves:

- Cotton gloves: Often available with rubber nubs (“friction dots”) to increase friction against items and improve grip. Friction dots can damage soft stone or ceramic surfaces. Cotton can deposit fibers onto material and can snag due to the weave of fabric and loose fit of the glove.

- Nitrile gloves: Are stable (unlikely to disintegrate) and allow for a reasonable grip. However, they may be too loose to handle extremely detailed or fragile items and they may tarnish silver items.

- Vinyl gloves: Can easily degrade. Typically considered inferior to nitrile gloves but may be an acceptable substitute for items that cannot be handled with bare hands when nitrile gloves are not available.

- Nylon gloves: Are often available with rubber nubs to increase friction against item and improve grip. However, these nubs (or “friction dots”) can damage soft stone or ceramic surfaces. Typically, they fit tighter than cotton gloves.

- Latex/Rubber gloves: Fit more tightly, but they degrade quickly and are easily torn. Latex/rubber gloves can damage metal surfaces. Many people also have allergies to latex. For these reasons, latex/rubber gloves are not recommended.

To learn more about gloves, see Handling & Preparation in the Exhibition Guidelines section of the PSAP User Manual in the Collection ID Guide.

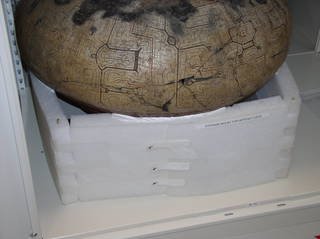

Properly Supporting Objects

No matter the shape, size, or material, objects and their parts must be properly supported in storage to prevent damage. Supports and cushions can protect and prevent items from moving or tipping in storage. Supports can be fashioned from polyethylene foam or acid-free tissue. Adequate cushions can be made out of materials as simple as Styrofoam packing peanuts in a plastic bag. Using supports underneath flat, oversize, or awkwardly-shaped objects can help handlers get a better grip underneath flat objects. Smaller items can also be stored in 2 mil or 4 mil polyethylene re-closable bags (fragments, particularly glass fragments, should always be kept in 4 ml re-closable polyethylene bags or boxes to minimize the risks of their causing damage to other objects). To learn more about object storage, see Storage of Objects in the Museum Objects in General section of the Collection ID Guide.

Object Enclosures

In general, objects should not be stored on shelving made of uncoated wood or anything that will off-gas. On the shelves and inside cabinets, there should be a buffer layer (a layer of acid-free tissue paper or polyethylene foam) between the shelf and the objects. Supports and cushioning fashioned from archival-grade/inert materials can also be used to protect and prevent items from moving or tipping in storage. Storage trays and boxes should also be made from archival-grade paperboard. Smaller items can be stored in 2 mil or 4 mil polyethylene re-closable bags.

Objects should not be stacked unless absolutely necessary, but if stacking is unavoidable, a layer of inert foam or acid-free tissue should be placed in between objects to avoid damage from contact. If open shelving is being used for object storage, items can be placed in archival boxes or acid-free tissue can be draped or wrapped around items to minimize dust accumulation and reduce the need for cleaning. Shelves should not wobble and drawers should have safety mechanisms so they cannot slide out all the way. Because objects can be heavy, care must be taken to ensure that shelving is in good repair and can support their weight. Do not store large items that do not fit on the shelves directly on the floor -- use risers to prevent the item from coming in contact with the floor.

Uncoated wood storage furniture should generally be avoided, but metal objects in particular should not be stored in unpainted wooden boxes, on unpainted wooden shelving, or near wood pulp or wooden materials (unpainted wood releases acetic acid which can cause metals to corrode over time). If choosing to store objects on or near painted wood, avoid oil-based and alkyd paints. Donated object materials may arrive in inappropriate enclosures (for example, regional museums often receive donations of archaeological projectile points in portable “exhibit boxes” that are made of wood). At the very least, collections that are received in improper housings should be removed from the detrimental enclosures and rehoused using archival quality/acid-free enclosures.

To learn more about object storage, see Storage of Objects in the Museum Objects in General section of the Collection ID Guide.

Large/Heavy Objects

Large object materials, particularly those made of dense stone, can be heavy (and are sometimes heavier than they look!). Care must be taken to ensure that shelving can support the weight of large/heavy objects. Heavy objects should only be stored on shelves that are easily accessible -- ideally at waist- or cart-level, so that they are less difficult to retrieve from shelves. Use an adequate number of people and adequate carts to transport stone objects. Never let the width of an object protrude past the width of a shelf. Do not store large items that do not fit on the shelves directly on the floor -- use risers to prevent the item from coming in contact with the floor. To learn more about object storage, see Storage of Objects in the Museum Objects in General section of the Collection ID Guide.

Security

Theft is a real threat, both when collections are on display and when items are in storage. It is necessary for every institution to implement and maintain a comprehensive security program to ensure the safety of employees, visitors, and the artifacts. At the very least, the rooms, furniture, and/or cases in which object materials are kept should be secured/locked, and access to those areas (or to keys to those areas) should be tracked and limited. Keys should be issued strictly on an as-needed basis. There is no reason for every staff or board member to have the key(s) to the storage areas or display cases, for instance.

Items on display are particularly vulnerable to theft. Be aware of placement and visibility in your space when designing exhibits. Objects that are often targets of theft include small objects that are easy to conceal in clothing (projectile points, for example). Metal objects (i.e., coins) and other items that are perceived as particularly “valuable” are also at high risk for theft. It is necessary to modify displays and exhibits to minimize risk. Any valuable or rare items, particularly those that are easily picked up and transported (and are therefore at higher risk), should be secured in locked cases/enclosures. To learn more about security, see Security in the Disaster Preparedness section of the PSAP User Manual in the Collection ID Guide.

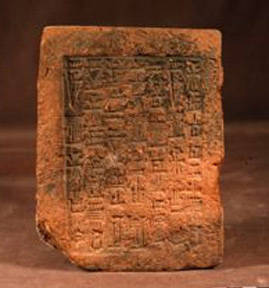

Physical Condition / Stability

Ceramics are made from natural materials/clay mixtures that are pliable when wet and shaped into particular forms that are then dried and/or fired to become hard/solid objects. Only when clay is fired at temperatures higher than 1652℉ (900℃) do the particles in the clay bond (a process called sintering) and become stronger. Full vitrification, which is the bonding of particles that results in the reduction of porosity, makes the clay more impermeable to water and occurs at even higher firing temperatures. While firing temperature largely determines the material strength of ceramic items, surface treatments and construction methods also have an impact on the strength, fragility, and preservation of ceramics.

Unfired and low-fired ceramics are porous and permeable to liquids - which makes them more susceptible to damage resulting from absorption of liquids in the environment. Archaeological ceramics, for example, often display evidence of salt efflorescence - which appears as a white haze on the surface of the ceramic object. Porous ceramics absorb soluble salts from the soil in which they are buried. Soluble salts will move in response to changes in humidity. The movement of soluble salts in the ceramic material can eventually cause the decorative surface or the body of the ceramic to crack or crumble.

While the surface of unfired and low-fired ceramics are more permeable to liquids, low- and unfired ceramics are typically tougher (and thicker) and not as brittle as high-fired ceramics. Porcelain and other high-fired ceramics, while less porous, are harder and more brittle, making them even more “fragile” and susceptible to impact and functional damage.

Flaws in the clay body or glaze layer of a ceramic can also reduce the overall stability of the object. Warping and cracking of the clay body during firing or crazing and blistering of the glaze, can all reduce the structural integrity of the ceramic object. Poor storage and irresponsible handling can cause and/or worsen damage or deterioration. Depending on the severity of the damage and/or deterioration, the object may be difficult or impossible to handle for research and/or display purposes, without causing more injury to the item. Read more about ceramics in the Collection ID Guide.

Structural Damage

While breaking, cracking, and other structural damage does not always indicate that an object is unstable (an object can be broken, but can still be considered in “good condition” or stable), structural damage can sometimes create weak points that are more vulnerable to additional damage, particularly if the item is handled. Cracks and breaks can also signal deterioration caused by chemical damage that has weakened the material structure of an item. Severe structural damage can compromise the integrity of the item, and may need added support or padding in storage to keep damage from worsening. Fragments and items with pieces missing may also need additional support to ensure that undue pressure is not placed on broken parts and that the item does not move or tip. Refer to Objects in General and Object Materials in the Collection ID Guide for more information on structural damage.

Previous Repairs

Failing previous repairs endanger the structural integrity of an object, and residue from old repairs can also cause damage (i.e., staining, delamination). Many repairs are visible under blacklight (UV), but many will also be visible to the naked eye. Materials used for previous repairs may have become unstable: old adhesives can discolor or become brittle, and metal or wooden splints and staples used to hold breaks may have degraded. Objects with previous repairs should be treated as highly fragile --- not only has the stability of an item been compromised by the original break, but aging adhesives, staples, and other fillers such as plaster of paris can continue to endanger the stability of the object. Degraded previous repairs can also stain or otherwise damage nearby materials, including other artifacts. Consult a conservator if you are concerned about the stability of a previous repair. Never attempt to reverse previous repairs without the assistance of an expert! More information can be found in Adhesives in the Supplementary section of the Collection ID Guide.

Previous Residue

Visible residue from previous use or accumulated material on the surface of an item should not be cleaned or removed, even to view the surface beneath. These residues may be useful for purposes of research and, if removed, can harm or seriously destabilize the object. An expert should be consulted if removal of previous residue is considered absolutely necessary.

Residue might take the form of active corrosion or damage. If this is the case, place the item in a microclimate (container) to slow deterioration and talk to a conservator about ways to prevent further deterioration. Residue from functional use, such as melted wax on candlesticks, is often preserved to secure the historical value of that item, but is occasionally removed by a conservation professional at the discretion of the institution. Cleaning museum objects is rarely recommended for non-experts, as damage often occurs as a result of inadvertent mishandling during cleaning. However, objects should be kept dust-free, so that accumulating dust does not cause further damage. Read more in Previous Residue in the Museum Objects in General section of the Collection ID Guide.

Damage from Mold / Biological Agents / Pest

When assessing the exposure of your collections to biological organisms, it is necessary to look not just at the materials themselves and their containers, but also at the larger environment. High humidity in collection spaces promotes the growth of biological agents (like mold and lichens) and insect infestation, both of which can cause permanent damage. Even inorganic object materials can be susceptible to mold, which may appear as fuzzy/downy patches in a variety of colors (often black, grey, or white). Mold can permeate the surface of the stone and create mechanical and chemical damage. Mold can also grow on enclosures and support materials that are in contact with museum objects.

Objects that were once buried, like archaeological glass, may exhibit growth of mosses or lichens. It is unlikely that these growths attack the glass directly, but moisture is often trapped between the growth and the surface layer, which can contribute to deterioration. Additionally, mosses, lichens, mold, and fungi may grow on stone. Lichens are aggressive weathering agents with the ability to penetrate the stone deeply. On stone, lichens may appear as grey, yellow, orange, green, or black round patches with a soft/powdery/leathery appearance. Lichen’s tendency to expand and contract in response to changes in humidity can weaken and damage the surface of stone.

Pests, like insects and rodents like the paper-based materials that may be used to house objects. Insects and rodents tend to leave droppings in areas they inhabit. Insects leave behind a substance called frass, which is the undigested fibers from paper. If you see droppings and/or frass in the storage area, it is a strong sign that your materials are being exposed to pests. Small, irregular holes on paper-based enclosures are also a sign that pests have attacked your materials.

Some tips for reducing your materials' exposure to pests are to refrain from eating anywhere near your collections materials. Crumbs draw pests, so eat far from your collections. Another tip applying to both pests and mold is to be cautious about donated materials when you receive them. Pests and mold can hitch a ride into your facility on these materials, so having a good, clean staging area where you can inspect donated items for, among other things, pest and mold evidence can help you reduce your storage environments' exposure to both.

Dust and Dirt

Dust and dirt that accumulate in the cavities of coarse surfaces and/or surfaces with etching, engraving, or other surface treatments can damage object materials. Dust is hygroscopic and will attract additional dust and dirt to the area, which can cause further damage. Accumulated dust and dirt can stain porous materials like some stone and ceramics. Dust that accrues on metal objects will retain moisture from the air, which may contain sulphur compounds or chlorides that can tarnish or accelerate corrosion of the metal.

Objects, particularly those with areas on the surface in which dust and dirt are likely to collect, should be placed in closed shelving, boxes, and/or covered with acid-free tissue to prevent dust buildup and reduce the need for handling while cleaning. Storage areas should be kept clean and free of dust.

Chemical Deterioration

Functional use, exposure to the elements, poor handling, and bad repairs can all bring about types of deterioration in ceramic objects. Often, deterioration is the result of a combination of these causes. Types of deterioration typically seen with ceramic objects include:

Crazing: a network of fine cracks that appear on the the surface of the glaze layer, which typically happens when the glaze surface layer contracts or shrinks at a rate faster than the clay body. Crazing may be visible right after firing, or may appear long after firing has taken place. While the glaze layer of low-fired and high-fired ceramics typically helps offer some impermeability, crazing of the glaze exposes the clay body leaving it susceptible to staining.

Salt Efflorescence: Contact with soil, food, or chemicals may cause ceramics to absorb water soluble salts, which can then re-crystallize and cause damage to the body and/or surface of the ceramics. Soluble salts react to changes in humidity, either becoming soluble in high humidity or crystallizing in low humidity. A white haze on the surface of a ceramic object is indicative of soluble salts in the body of the object. Over time, the movement of soluble salts will cause the decorative surface or the body of the ceramic to crack or crumble. Archaeological or buried ceramics are particularly susceptible to this type of damage, as they absorb soluble salts from the soil in which they are buried. Non-archaeological objects may absorb soluble salts throughout their everyday use. Soluble salt damage is more likely to be seen on more-porous unfired and low-fired ceramics. High-fired ceramics that are fully vitrified, like porcelain, are waterproof and thus impervious to damage from soluble salts.

Staining and Encrustations: Ceramics with crazing or chips in their glazes can become stained by food and other materials that may seep through the breaks in the glaze and stain the porous ceramic below. In addition, ceramics can become stained when they come in contact with iron (when buried) or other metals, for example: corroding metal supports from a previous repair.

Acid attack: Some glazes may lose their transparency as the result of acid deterioration. If a ceramic item is in long-term contact with an acidic substance, the acid can dissolve calcareous (composed of calcium carbonate) fillers in the body of the item and leave the object looking porous. Crystalline or ‘artistic’ glazes, especially those which contain metal compounds, are susceptible acid attack. Stoneware and porcelain glazes, which have fewer metals, are less susceptible to acid attack.

Alkaline attack: Is a type of deterioration that occurs with glass, including ceramic glazes, which are chemically like glass. More likely to occur in humid and warm environments, alkaline attack may result in the surface of the glaze changing color or appearing iridescent.

Lead sulphide blackening: Under certain conditions, the growth of sulphite reducing bacteria associated with decaying plant and animal tissues may cause the blackening of lead glazes.

Read more about ceramics in the Collection ID Guide.